What is lobbying in politics?

Lobbying is a catch-all term to describe ‘special interest’ groups and their tactics to gain influence in the political process, particularly around the shaping of legislation and government policy.

Over the years, British politics has not been without its lobbying scandals.

Historians of the eighteenth century have suggested that Britain’s first Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole (1721-1742), became personally enriched during his tenure in office. Some Twentieth century historians have also suggested that Winston Churchill was himself unduly influenced in relation to the handling of access to the Persian oil reserves.

More recently, in the mid 1990s, British politics became engulfed in a series of cash for access, and cash for questions scandals. This played to a narrative of greediness on the part of a few individual politicians. In 1997, it led to the BBC Journalist, Sir Martin Bell, successfully standing on an anti-sleaze ticket for election to Parliament in the constituency of Tatton.

How clean is British politics today?

Studies have suggested that British politics is relatively clean, certainly when compared to the experience of many other countries.

Indeed in 2020, the United Kingdom was placed in joint eleventh placed in the global ‘Corruption Perceptions Index’ generated by the group Transparency International. The UK ranked below Denmark which topped the list, and below Germany (9th place).

However the UK was perceived as being notably less corrupt than Ireland (in 20th place), the United States of America (in 25th place), and Italy (in 52nd place).

Nonetheless in 2021, fresh attention was focussed on UK lobbying after controversies involving the former MP Owen Patterson, and former Prime Minister, David Cameron.

The UK lobbying industry

Political Lobbying firms act on behalf of third parties, pursuing influence strategies designed to alter government decision-making so to correspond with their organization’s interests.

Lobbying derives its name from the lobbies or hallways of Parliament where MPs and Lords gather before debates and votes.

After the term ‘lobbying’ became something of a dirty word in the late 1990s, the UK’s leading lobbying companies re-branded themselves as ‘public affairs firms’, ‘government relations’ advisors, or ‘political consultancies’.

The political lobbying industry moved more actively to try and place itself within the wider umbrella of the public relations industry.

The Hansard Society has since estimated that Members of Parliament are approached over 100 times a week by lobbyists.

Defenders of the lobbying industry argue that lobbying firms provide an important function in politics – conveying the views of stakeholders to policymakers, and generating better legislation as result.

Critics of the lobbying industry highlight its lack of transparency, and the undue influence that it can potentially offer to an interest group or non-elected individual.

Lobbying techniques

The best-known lobbying tactic involves seeking out one to one conversations with Government Ministers, Civil Servants, and Members of Parliament.

This process is more subtle than a chance encounter. Lobbying firms frequently market themselves on the basis of their contacts and knowledge base. Many employees of these firms are typically active in a political party, and on many occasions, the senior leadership of the companies is populated by ex-politicians themselves.

In a 2009 report on lobbying in the UK, Lord Maclennan of Rogart said: ‘[lobbying] can be done very subtly and without necessarily going through any transparent channels’. The influence of lobbyists is said to be at its greatest, when their activities go largely unnoticed by the public.

However in a pluralist age, where the merits of an issue are more fully discussed in the press, social media, and online, lobbyists have though had to widen their tactics.

One particular technique that lobbyists seek to use is that of ‘debate framing’. Their challenge is to develop language around a particular political issue in order to make it appear more attractive and palatable to the public and politicians alike. On one level, this is little more than marketing. However, in the context of a narrowly framed discussion, dissenting voices can appear marginal and irrelevant.

So for example, faced with potentially unwelcome environmental impacts, a lobbyist employed by a fracking firm might chose to frame that debate around economics and the benefits being brought to a particular local community. Tapping into concerns around global warming, representatives from the Nuclear industry, might stress the benefits of nuclear as ‘climate friendly energy’, tapping into the public feeling that climate change is an issue that really needs solving.

On occasion, it has been suggested that a particular lobbying or corporate firm might engage in more defensive techniques as part of attempts to neutralize potential opponents. Techniques within this realm have been said to involve driving a deliberate wedge between different opposition groups, positioning opponents as extremists, and closely monitoring the activities of opposing political activists.

Regulation of lobbyists

The regulation of lobbyists has always been a difficult task, not least because it is difficult to regulate what is not fully known or understood.

In 2009, then Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown announced that he would act upon the recommendations of a Commons Committee in relation to lobbying.

Brown decreed that Government Departments would henceforth have to publish online quarterly reports detailing Ministerial meetings with interest groups. Brown’s Labour government nonetheless rejected a mandatory register of lobby groups, prompting the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency to claim that, ‘self-regulation is no regulation’.

In 2013, the Conservative Government of David Cameron introduced a bill calling more transparency in lobbying. The eventual ‘Transparency of Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014’ set up the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists (ORCL). This change required some lobby groups to sign up to a lobbying register online. However, once again, for critics this did not go far enough.

The campaign group, ‘Transparency International’, have suggested that just a small fraction of UK lobbyists are actually covered by the register.

In late November 2021, the Hose of Commons Committee on Standards published a series of recommendations to further tighten the rules around lobbying.

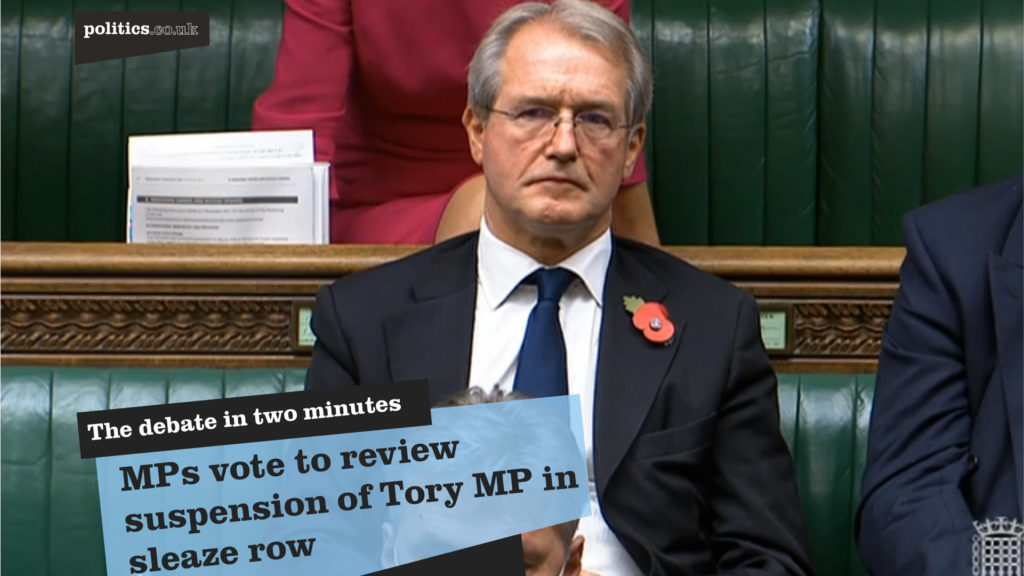

The resignation of Owen Patterson

In early November 2021, Owen Patterson resigned as the Conservative MP for North Shropshire. He previously served in the Cabinet as the Northern Ireland secretary and environment secretary under David Cameron.

After leaving government, Patterson took up roles as a paid consultant for Randox Laboratories and Lynn’s Country Foods.

Patterson was later investigated by the Commissioner for Parliamentary Standards after being accused of breaking lobbying rules for MPs.

The commissioner found that on behalf of the companies, he had approached and on a number of occassions met officials at the Food Standards Agency and ministers at the Department for International Development. In the Commissioner’s report, he was accused of using his parliamentary office and stationery for consultancy work and for failing to declare his interests in certain meetings.

The commissioner concluded that Patterson’s actions amounted to “serious breaches” of the rules and recommended a 30 day Commons suspension, something which in itself could have led to recall petition and a by-election in his constituency.

Mr Patterson was critical of the way in which the Parliamentary Commissioner had conducted the investigation into his conduct. With government support, the Commons initially approved a pause in relation to Mr Patterson’s suspension and voted to overhaul the system by which MPs were invesigated. However following a notable political fallout, that proposed overhaul was shelved and Mr Patterson announced that he would be resigning as an MP.

Two weeks later, and in the face of falling poll ratings, Prime Minister Boris Johnson moved to set out plans to stop MPs from working as paid consultants. The proposal had previously been made in a 2018 report from the ethics watchdog, the Committee on Standards in Public Life. It was thought likely to restrict the current activities of as many of 30 MPs.

Cameron and the Grensill affair

Before becoming Prime Minister in 2010, David Cameron had won plaudits for his anti-lobbying, anti-corruption platform, which faired well amongst an electorate critical of New Labour’s proximity to big business.

In the aftermath of the 2009 scandal surrounding MPs expense claims, the then Conservative Leader, David Cameron ironiclally mused that lobbying would be the next big political scandal. He suggested the political lobbying industry might be as large as £2 billion and described it as having a ‘huge presence’ in parliament:

“We all know how it works. The lunches, the hospitality, the quiet word in your ear, the ex-ministers and ex-advisers for hire, helping big business find the right way to get its way. In this party, we believe in competition, not cronyism” – David Cameron, 2010

The rules on business appointments, published in 2014, state that ‘on leaving office, ministers will be prohibited from lobbying government for two years’. Cameron stood down as PM in July 2016 and joined the financial services company, Greensill Capital, in August 2018 as an adviser.

In April 2021,it was revealed that Cameron had personally lobbied key Government ministers on behalf of the now-collapsed Greensill so that the company might gain access to coronavirus loan schemes.

In 2020, Cameron had sent texts to Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor and reportedly phoned two other Treasury ministers. In 2019, Cameron reportedly organised a ‘private drink’ with himself, Matt Hancock (the then Health Secretary) and Lex Greensill (the founder of Greensill Capital).

In a statement responding to the affair, Cameron claimed that, ‘I complied with the rules and my interventions did not lead to a change in the Government’s approach to the Covid Corporate Financing Facility’.

Seely pushes for foreign lobbying reform to ‘defend open society’

Standards Committee announce plans to tighten lobbying rules

‘This is a painful day’ – Cameron questioned in Greensill inquiry

Standards Committee announce plans to tighten lobbying rules

Political donations

It has been suggested that those who donate to political parties are likely to be able to gain more privileged access to decision making.

Controversy around the issue of political donations really jumped to public consciousness in 1997. Shortly after the Blair government had come to power, it emerged that Formula One supremo, Bernie Ecclestein, in January 1997 had donated £1 million to the Labour Party ahead of the ensuing General Election.

That donation had not been made public at that time, but media interest piqued, when shortly after being elected in the Summer of 1997, the new government announced its plans to regulate the role of tobacco advertising in sport. However this was not set to apply to all sport. A notable exemption appeared to have been made for motor racing.

Later that year, news of Mr Ecclestein’s earlier donation to the Labour Party seeped out, and to no small amount of public controversy. In November of 1997, Prime Minister Blair took the unusual step of apologising on television for his government’s handling of the Formula One decision.

Perhaps now slightly tarnished by the Ecclestein affair, in 2000 the Blair government brought forward the ‘Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000’. This legislation now mandated political parties to report central donations of over £7,500, and local donations of over £1,500, to the Electoral Commission.

Parliamentary access passes

One particularly controversial feature of the debate around lobbying in the United Kingdom surrounds the issue of Parliamentary Access Passes.

As discussed earlier, it is a well-known practice for lobbyists to hire ex-MPs and ex-Ministers in the course of lobbying work.

What is perhaps less well known, is that ex MPs (both those who have retired, or those who have been rejected by the electorate) have the right to apply for a Parliamentary Access Pass. This pass grants the former Member of Parliament easy access to the Palace of Westminster, including access to its restaurants and bars, notable for their quality and value. For those who become subsequently engaged in lobbying, these passes are thought to be particularly helpful.

It is worth reflecting that not all workplaces provide their former employees with such simple and free access back onto their premises.

A 2020 Freedom of Information Act request by the Guardian newspaper found that 324 former MPs had used their parliamentary passes in a single year, with one doing so on as many as 82 occasions within a calendar year. Although such passes are not supposed to be used for lobbying purposes, the Guardian’s investigation observed how the stated work activities of many of these ex MPs, could lead people to construe that they were now professionally at least, employed in some form of lobbying capacity.

In November 2021, the Commons Speaker Lydnsay Hoyle signalled his opposition to the practice. He told the Commons, that, “If you’re a lobbyist, I don’t think it’s right they should have a pass for this House. Absolutely not.”