Support for Scottish independence has increased steadily in recent decades. Where polling suggested little more than 10% of Scots favoured independence in the early 1980s, the figure had risen to 30% by the late 1980s. It has remained well above 40% throughout the last decade with 44.7% of Scots backing independence in the 2014 independence referendum.

The case made for Scottish independence

Proponents of an independent Scotland draw heavily on the following arguments:

Self-determination

The loudest arguments made around Scottish independence focus on the issue of self-determination. In essence, proponents of independence argue that Scotland is a distinct nation separate from the rest of the United Kingdom, and accordingly it should control its full political authority as an independent sovereign nation-state.

Historically, Scotland was an independent country until the 1707 Acts of Union united Scotland with England and Wales in the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Political identity

Following the growing dominance of the SNP and its sustained electoral success in elections for the Scottish Parliament, Scottish nationalists also question the authority of the Conservative government to retain any remaining powers over Scotland.

In terms of political identity, Scotland has traditionally sat further left than England on the political spectrum. Even though a large number of powers are now held by the Scottish Parliament, supporters of Scottish Independence, point to the benefit of being free from Conservative Governments in Westminster.

Nuclear Weapons.

The Scottish National Party is unequivocal in its opposition to nuclear weapons, and the stationing of the UK nuclear deterrent at the Faslane naval base in Scotland, in particular. It is argued that Scottish Independence would lead to the removal of nuclear weapons from Scotland.

EU Membership.

Those Scots opposed to Britain’s departure from the European Union following the 2016 Brexit referendum have suggested that an independent Scotland would have the opportunity to rejoin the European Union. The European Union, keen not to encourage separatist voices in other parts of Europe such as Catalonia, have though hitherto, remained coy, about such prospects.

Arguments – The case made against Scottish independence

Opponents of an independent Scotland argue that the powers of the Scottish Parliament have now increased considerably since it was first established in 1998. Emphasising the benefits of the Union and the uncertainty around independence, the arguments typically voiced by those opposed to Independence include:

Diminished international influence, for both UK and an independent Scotland.

The United Kingdom as a whole is said to currently retain a great deal of influence on the world stage, despite its relatively small population size.

It is suggested that the departure of Scotland from the UK would create a domino effect that would likely reduce the influence of both the UK, and of Scotland, on the world stage. Where the UK is currently a member of the G7 and the G20, and has a permanent place on the United Nations Security Council, it is argued that an independent Scotland would lose all such influence.

Reduced Revenues from UK Funds

Calculated under the Barnett formula, the Block Grant for Scotland results in proportionally greater funding per head of population than in England.

Opponents of Scottish independence, use this statistic to argue that an independent Scotland would be financially worse off, and that England would conversely be better off.

Economic Uncertainty

At present, over 60% of Scottish exports go to England, Wales and Northern Ireland; more than the rest of the world combined.

It is argued that, withdrawing from the United Kingdom might lead to a situation in which an Independent Scotland would not have the current unfettered access to its major market, and that this would result in economic uncertainty, and potential economic decline.

Opponents of Scottish Independence have also argued that concern about which currency an independent Scotland may use, and how that would operate, would further deter inward investment into Scotland.

Issues with regaining EU Membership

Those opposed to Scottish Independence argue that it is far from likely that Scotland will be able to rejoin the European Union. It is thought that those European governments which are facing separatist challenges, such as Spain, wouldbe unwilling to legitimise an independent Scotland and thereby incentivise their own separatist movements.

The former leader of Scottish Conservatives, Ruth Davidson, has famously described the ‘independence because of Brexit’ argument as the political equivalent of “amputating your foot because you’ve stubbed your toe”.

Others have also pointed to the irony of supporters for Scottish independence being motivated by their desire not to defer power to Westminster, but at the same time, being seemingly enthusiastic for a newly independent Scotland to then defer its powers to Brussels.

Scotland’s Internal Security

Opponents of Scottish Independence have also argued that an Independent Scotland would not be able to replicate the extensive security apparatus available to Scotland within the United Kingdom.

It is argued that an independent Scotland would lose access to the Five Eyes international security network towhich the UK belongs, and the advanced cybersecurity capabilities provided by GCHQ and the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure.

Issues to resolve should Scotland ever become independent

In the event that Scottish voters were given the opportunity to vote again on independence, and chose to support separation, a host of practical problems would result in lengthy negotiations between the rest of the UK and the newly independent Scotland.

These questions would likely focus on the following areas in particular:

Currency

A number of proposals have been made as to the approach that an Independent Scotland may adopt in relation to the currency it uses. Some have suggested that Scotland would keep the pound under an arrangement termed “adaptive sterlingisation”, whereby an independent Scotland would adopt a policy of unilateral use of the pound outside a currency union. Others have suggested that Scotland may seek to switch to the Euro.

The choice of currency is amongst a number of issues that would need to be resolved for an independent Scotland.

The National Debt

An agreement would need to be reached as to Scotland’s share of the United Kingdom’s existing national debt burden. Given the size of the current national debt is worth about 100% of the UK’s GDP, discussions in this area would likely prove particularly problematic and difficult.

Scotland’s National Security

Post any independence vote, questions would arise concerning the distribution of the UK’s current military resources. The same would relate to the extent to which a new Scottish government would retain access, if at all, to resources such as MI5 and GCHQ.

Going in the other direction, there would likely be tense discussions around the speed of the relocation of the UK’s nuclear deterrent away from Scotland. This may prove problematic, given the likely cost, time, and difficulties involved in establishing an alternative base for the UK’s nuclear arsenal.

Head of State

The Scottish National Party have proposed maintaining the Kingas Head of State of an independent Scotland. Some in Scottish nationalist circles, mirroring the official republican party policy of Plaid Cymru in Wales, oppose this idea.

They argue that it is counterintuitive to retain the monarchy, given the desire to break Scotland away from what is sometimes characterised as ‘centuries of subjugation’.

The Border

The UK remains the biggest trading partner for Scotland. Agreements would need to be agreed to enable the seamless flow of imports and exports. It is unclear as to the extent to which either side would wish for customs posts and border checks to be introduced.

Access to Public Services

It is likely that some form of reciprocal arrangements would need to be put in place between a newly independent Scotland and the rest of the UK in relation to the potential mutual access to public services, particularly around health care and consular services.

Further separatist waves

Any decision by the Scottish people to vote for independence would likely have a further de-stabilising effect on the remainder of the United Kingdom. It has been suggested that support for other independence causes, particularly Welsh Independence and a United Ireland would gain momentum and draw inspiration from Scotland.

At the same time, it has also been suggested that separatist movements in the Orkneys and Shetland, may gain further impetus should an independent Scotland come into being.

These groups have called on the Islands to be able to tap into their own natural resources, moving to an independent setup such as that of the Faroe Islands. In July 2023, it was reported that Orkney council were looking into proposals to become a self-governing territory of Norway.

It is thought that having gained its own independence, an independent Scotland may find it difficult to deny the same rights to those in the Orkneys and the Shetland Islands should they wish for it.

Rising calls for Scottish independence

As a result of sustained public pressure, and an increase in the representation of the Scottish National Party at Westminster, a referendum on the devolution of powers to a new Scottish Parliament was first held in 1979.

In that year’s referendum, 51% of Scottish voters supported devolution, but on a turnout of 64%, thereby representing just 32% of the total electorate. The then Labour government had stipulated as a condition of the referendum, that devolution needed to be supported by 40% of the electorate as a whole in order to go ahead.

A second referendum on Scottish devolution was held in 1997 and without any turnout stipulation. With 74.2% of Scots supporting devolution, the Scottish Parliament was established under the Scotland Act 1998. Composed of 129 elected representatives and located opposite Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, the Scottish Parliament gained the power to legislate across a range of policy areas.

In a 2007, the Scottish National Party (SNP) first gained power in the Scottish Parliament. The party’s new First Minister, Alex Salmond, brought forward a white paper articulating the prospects for Scotland’s constitutional future. Salmond wrote that, “No change was no longer an option”.

In the ensuing 2011 elections for the Scottish Parliament , the SNP won an outright majority of seats and gained 44.7% of the vote. In the wake of the party’s continuing political impetus, the SNP launched an official drive for independence.

In October 2012, the Scottish and UK governments signed an Agreement authorising a Scottish Independence Referendum. For the first time in Scottish history, 16 and 17-year-olds were also granted the right to vote.

On Thursday 18 September 2014, an independence referendum was held to decide whether Scotland would be granted independence from the United Kingdom. Attracting the highest voter turnout in Scotland since 1910, 55.3% of Scottish Voters chose to oppose Scottish independence.

Despite their loss in that first independence referendum (IndyRef1), the SNP have remained electorally dominant in Scotland. The debate around Scottish Independence was then injected with a new dynamic following the 2016 decision by voters in the United Kingdom as a whole (but not in Scotland) to vote for Britain to leave the European Union.

Buoyed by 2020 polls that suggest that a majority of Scottish voters favoured independence, the Scottish National Party went into the 2021 Scottish Parliament elections actively campaigning for a second referendum on Scottish Independence (IndyRef2). Returning to government in 2021 with the support of the pro-independence Scottish Green Party, the Scottish government now claims it has an electoral mandate to bring forward proposals for a second Scottish Independence Referendum.

However, the appetite for independence took a hit in 2023. Since January 2023, Politco’s Poll of Polls has found more are against holding a second independence referendum than against it.

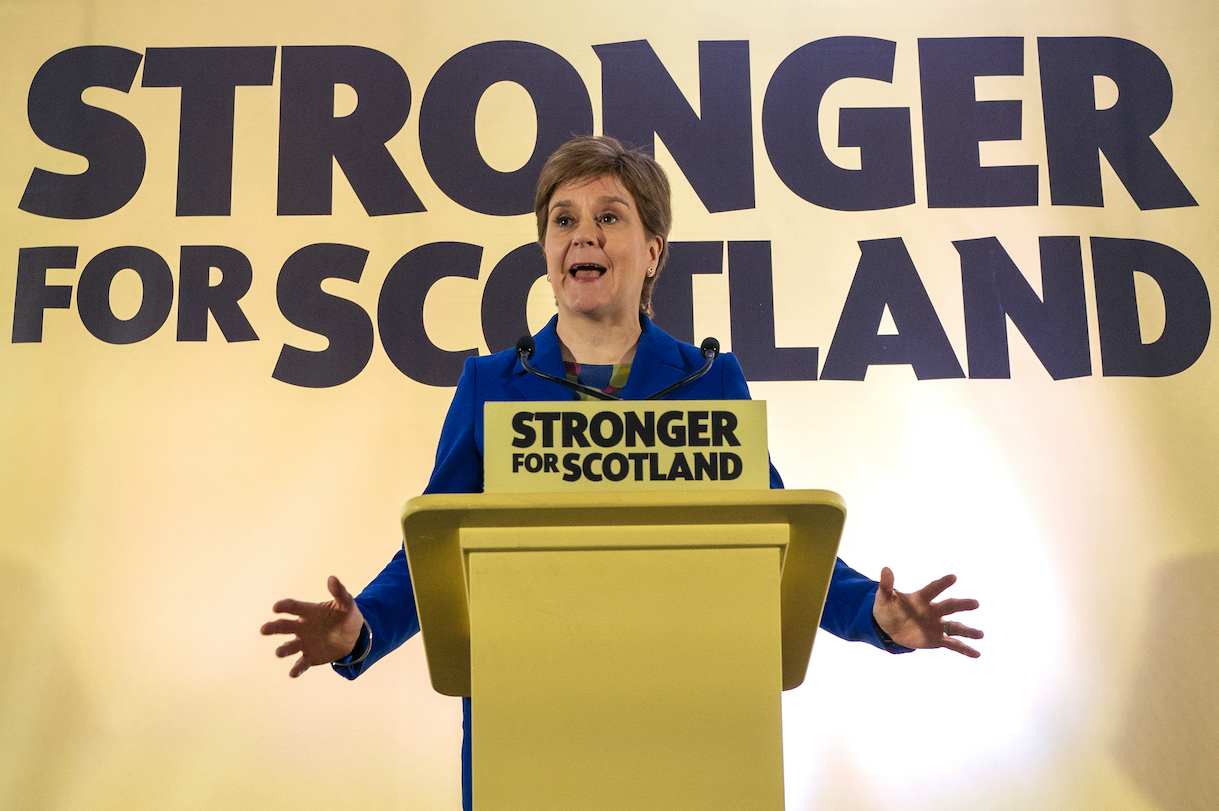

The Scottish National Party, the party which has spearheaded the independence movement in recent years has been mired in controversy.A police probe into the party’s finances has led to the arrests of senior party figures, including the former leader Nicola Sturgeon.

Furthermore, members of a focus group convened by More in Common UK found that the new SNP leader, Humza Yousaf, found his public profile is not as strong as Ms Sturgeon’s. More immediate concerns about heating and housing trump their desire for another referendum.

Yougov’s Holyrood voting intention tracker found that SNP is 16 points below its peak in 2020 and Labour is catching up to their unrivalled lead for the last 10 years.

Scottish independence – Quotes

“No one, absolutely no one, will do a better job of running Scotland than the people who live and work in Scotland. On September 18, we have the opportunity of a lifetime”. First Minister Alex Salmond, August 2014.

People can feel it is a bit like a general election, that you make a decision and five years later you can make another decision… if you’re fed up with the effing Tories give them a kick. This is totally different from a general election, this is a decision about not the next five years, it’s a decision about the next century. – David Cameron, Prime Minister, 2014.

The more I listen to the ‘Yes’ campaign, the more I worry about its minimisation and even denial of risks. Whenever the big issues are raised – our heavy reliance on oil revenue if we become independent, what currency we’ll use, whether we’ll get back into the EU – reasonable questions are drowned out by accusations of ‘scaremongering’” – Author JK Rowling, and a backer in 2014 of the No Campaign against Scottish Independence.

“Huge day for Scotland today! No campaign negativity last few days totally swayed my view on it. Excited to see the outcome. Lets do this!” – Andy Murray, Scottish Tennis Player, 2014.

“The United Kingdom has been an extraordinary partner to us – from the outside at least it looks like things have worked pretty well and we obviously have a deep interest in making sure that one of the closest allies that we will ever have remains (a) strong, robust, united and effective partner” – US President Barack Obama, 2014..

“It is the Scots who have succeeded most in preserving the British idea of fairness and compassion in terms of state support and intervention. Ironically, it is England, since the 1980s, which has embarked on a separate journey” – Leading Scottish historian Tom Devine, 2014.

“I think we should have an English vote first and let England make the first move – if they want us to leave, then we’ll stay.” – Scottish Comedian Kevin Bridges.

“I think the Scots will come to a good conclusion in the referendum. They’ll get what they deserve”.

Scottish comedian Billy Connolly in 2014, saying he planned to be out of the country for the referendum and would not vote.

‘The settled will’: Scottish sovereignty in an age of unthinking unionism

Unionists must tell us what they’re for, not just what they’re against

The break-up of the UK is coming – but will it be violent or peaceful?