Overview

Following the first referendum on Scottish Independence in 2014 (IndyRef1), support for the Scottish National Party has remained high, and through much of of 2021 polls were suggesting constant public support for Scottish Independence. This has led to a debate around the holding o a second public vote (IndyRef2).

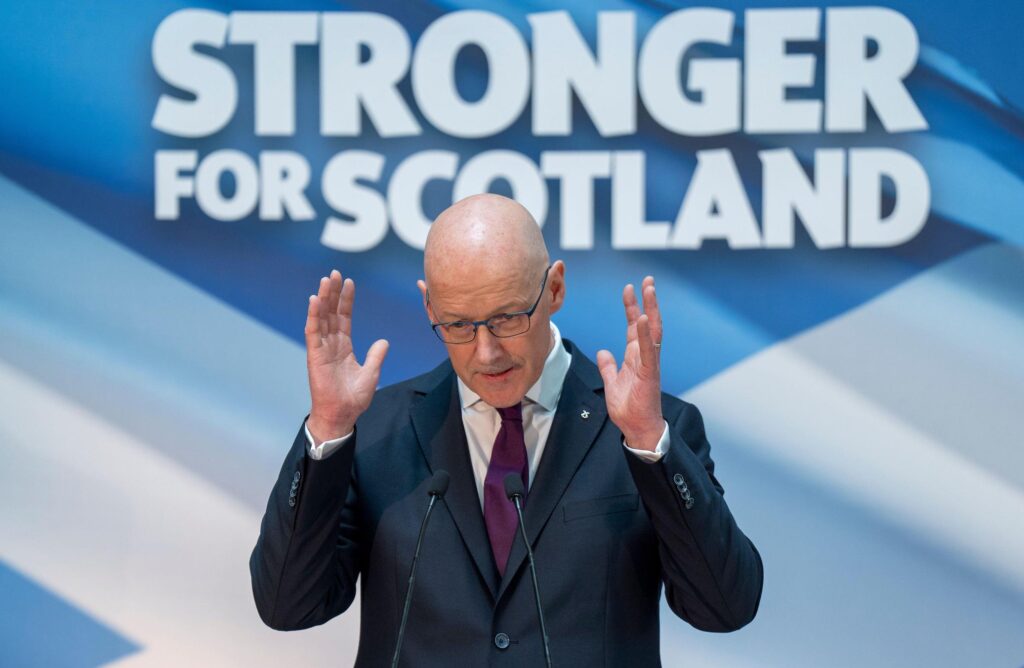

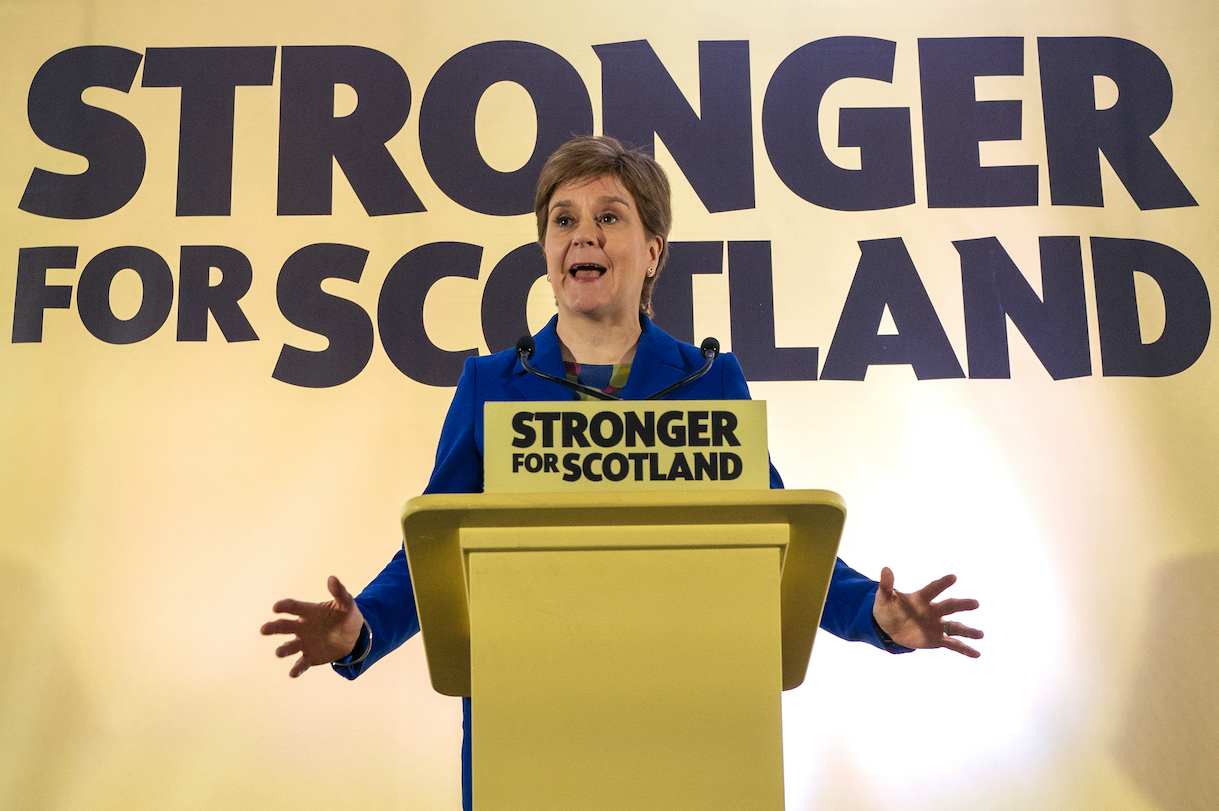

Returning to power after the 2021 Scottish Parliament elections, the SNP led Scottish government argued that it now has an electoral mandate to hold a second Scottish Independence Referendum within the next couple of years. In June 2022, Scottish first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, announced she was formally beginning the campaign for indyref2.

Former Scottish first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, announced her government’s intention to hold a second Independence Referendum on 19 October 2023.

However, then British prime minister Boris Johnson refused to recognise the pro-independence majority in the Scottish parliament, the basis used back in 2014, as a mandate for a second independence referendum.

In November 2022, the UK Supreme Court ruled that the Scottish Parliament did not possess the power to organise its own referendum without Westminster’s approval. The judgement in effect meant that one part of the United Kingdom was not able to leave the Union without the consent of the others.

IndyRef2 and the powers of the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament was established through the 1998 Scotland Act.

The Scotland Act specified the areas where the Scottish Parliament had decision making capability. Working off a reserved powers model, the Scottish Parliament has legal power over all areas apart from those which remained ‘reserved’ for Westminster.

Under the 2012 Scotland Act and 2015-16 Scotland Act, further powers were transferred to the Scottish Parliament, and the number of reserved areas decreased.

However, despite the subsequent expanding of the legislative powers of the Scottish Parliament, a number of reserved powers remain with Westminster. In particular these relate to matters concerning the constitution, immigration, foreign affairs, defence policy, and the Union of the United Kingdom.

As such, in order for the Scottish Parliament to legislate on an independence referendum, a Section 30 order would still need to be granted by the UK government. Section 30 is the section of the Scotland Act that allows Holyrood to pass laws in areas that are normally reserved to Westminster. This could temporarily devolve powers from the Scottish Government and authorise the Scottish Parliament to hold a legally binding Scottish Independence Referendum.

Section 30 of the Act has so far been invoked on 16 occasions since the Scottish Parliament was first established. For example it was used to allow Edinburgh to legislate on railway construction, and to reduce the voting age to 16 in Scottish Parliament elections.

Most famously a Section 30 was used in 2014 to authorise the first Scottish Independence referendum, after David Cameron and Alex Salmond signed the ‘Edinburgh Agreement’.

How might a second Scottish referendum come about?

The UK government has so far firmly pushed back against any notion of an IndyRef2, referring to discussions at the time which labelled the previous Scottish Independence referendum as a once in a generation event.

Prior to the 2021 Scottish Parliament elections, Dennis Canavan, Chair of the 2014 Campaign for Scottish Independence stated: “If the people of Scotland vote at the May 2021 elections to give the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government an unequivocal mandate for IndyRef2, then I think the public mood would be in favour of holding IndyRef2 as soon as practicable”.

In 2021, the SNP was reelected to government with 47.7% of the constituency vote, gaining 64 of Holyrood’s 129 seats.

The continuing opposition from both the Conservative and Labour Party at Westminster to any notion of a Second Scottish Independence Referendum has prompted debate as to how such a vote might come to pass. Where there was a consensus in 2014 between Westminster and Holyrood about an independence vote, there is no such consensus behind a second such poll.

Former SNP Leader, Nicola Sturgeon, ruled out a Catalonia inspired unauthorised vote, insisting that such votes don’t lead to independence. The potency of such a ballot might be called into question, if a large proportion of the electorate (potentially pro Union voters) then chose not to participate in what was only a consultative referendum.

The central case currently being made for a second Scottish Independence Referendum is being driven by polling, and the 2021 Scottish Parliament election result.

A 2020 poll conducted by Ipsos MORI found that 58% of Scotland would now vote Yes in a second referendum, with polls at the turn of 2020/2021 all constantly showing support for Scottish Independence. The existence of these polls is the primary justification that is given for the need for an IndyRef2, along the lines that these majorities determine that the Scottish people now have a right to determine their own destiny once more.

With the SNP going into the 2021 Scottish Parliament elections with a manifesto that included a pledge to hold an IndyRef2, the SNP can also now claim to have an electoral mandate for a second democratic vote on Scottish independence. In light of the SNP victory, First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon argued that anyone opposing IndyRef2 was “not picking a fight with the SNP, but with the democratic wishes of the Scottish people”,

The Scottish National Party has also claimed that the 2016 Brexit referendum, which took Scotland out of the European Union, against the wishes of people in Scotland, also constitutes a justification for the holding of a second public vote on Scottish Independence. In this sense, the party argues that the circumstances are now very different to those that were discussed in the 2014 vote.

The case against IndyRef2

The argument against IndyRef2 is primarily based on the fact that referendums, are once in a generation events.

A comparison is drawn between the fifty years that passed between the public vote on Britain joining the EEC in 1974, and the Brexit referendum in 2016. It is argued that it is simply too soon after the previous vote to be holding a fresh referendum.

It is noted that public opinion can change dramatically year on year, and whilst there may be narrow support for independence in the opinion polls at one point, such support might be short lived, and does not constitute the basis for regularly revisiting the constitutional question.

The argument is made that should Scottish Independence be granted, but then prove unpopular after a few years, it would be unlikely that a public vote would be considered appropriate in terms of rejoining the United Kingdom.

It is further claimed that the political and economic problems emerging out of the Covid 19 pandemic have created a whole range of pressing policy challenges. It is argued that IndyRef2 would get in the way of dealing with these matters. In 2020, the Scottish Conservative leader, Douglas Ross said, “It would be irresponsible in the extreme to keep diverting precious time and civil servants’ attention away from the most important issues – like the vaccine delivery, education and protecting jobs – and onto another divisive referendum instead.”.

Those opposed to a second Scottish Independence Referendum also question whether, despite their electoral victory in 2021, the SNP have a sufficient electoral mandate for IndyRef2. They point to the fact that the SNP failed to win either an outright majority of seats in the 2021 Scottish Parliament elections, and the fact that the party failed to win a majority of the constituency vote (47.7%).

In response, the SNP responds that this share of the vote was far higher than that achieved by David Cameron before initiating the 2016 Brexit referendum. They also argue that a majority of MSPs (both SNP and Scottish Greens) stood on election manifestos that were committed to an IndyRef2.

IndyRef2 – Recent Historical Context

The Run up to IndyRef1

From its establishment in 1999, the Scottish Parliament had been dominated by the Labour Party. However, this all changed in 2007, when the Scottish National Party (SNP) gained more seats than Labour in that year’s Holyrood elections, and went on to form the SNP’s first minority government.

This change in power marked a significant shift in the agenda and narrative of Scottish politics.

In a 2007 white paper articulating the prospects for Scotland’s constitutional future, First Minister Alex Salmond wrote that: “No change was no longer an option”.

In the Holyrood election of 2011, the SNP further increased its support securing 44.7% of the vote, and winning 69 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament. In the wake of this political impetus, the SNP launched an official drive for independence.

In October of 2012, the Scottish and UK governments signed an Agreement authorising a Referendum on Scottish Independence. For the first time in Scottish history, 16 and 17-year-olds were granted the right to vote.

On Thursday 18 September 2014, a referendum was held to decide whether Scotland would be granted independence from the United Kingdom. Attracting the highest voter turnout since 1910, the No Campaign was victorious, gaining 55.3% of the vote.

The gradual build up of calls for IndyRef2

Despite their defeat in IndyRef1, the Scottish National Party’s electoral dominance has remained strong after the first public vote. The SNP has now remained in government in Holyrood continuously since 2007.

In the 2015 UK General Election, support for the Scottish National Party continued to rise, and the party won 50% of the vote in Scotland, winning 56 out of Scotland’s 59 seats at Westminster. Although the party lost 21 of those seats in the 2017 General Election, it managed to climb back to the 48 seat mark in the 2019 General Election.

The Brexit referendum result of 2016 was seen to further support calls for an IndyRef2 and boost support for Scottish Independence. For whilst 52% of voters in the UK as a whole had voted to leave the European Union, within Scotland, some 62% of voters had voted to remain.

During 2020 and 2021, the Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic saw a further rise in her popularity. Moreover this rise in popularity was common across Unionist and Independence voters. Among younger voters, polls suggested that 79% of those aged 16-24, many of whom were too young to vote in IndyRef1, would vote for Independence.

The Scottish National Party adopted a firm policy position of calling for an IndyRef2, and contained such proposals in its 2021 manifesto for elections to the Scottish Parliament.

Following its return to power after these elections, the Scottish government now claims it has an electoral mandate to hold an IndyRef2. Although resistance to a second referendum remains strong in some quarters, other Pro Union voices, have suggested that refusing IndyRef2 would now be a strategic mistake, only further fuelling the flames of Scottish Independence.

In June 2022, the Scottish government published legal advice which suggested that it was entitled to consult on the wording of a potential question to be used in any ‘IndyRef2’.

Quotes

“Independence is in clear sight – and if we show unity of purpose, humility and hard work, I have never been so certain that we will deliver it. – First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, 2020

“If people in Scotland vote for a referendum, there will be a referendum. Across the Atlantic, even Trump is having to concede the outcome of a fair and free democratic election.” – First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, 2020

“A second referendum would “continue the political stagnation Scotland has seen for the past decade” – Prime Minister Boris Johnson, 2020

“I don’t think there should be another referendum. I don’t think a further, divisive referendum is the right way forward. But I do accept that the status quo isn’t working.” – Keir Starmer, 2020

Statistics

40 per cent of Scottish voters believe a second independence referendum should happen within the next two years, with 15 per cent saying five years should pass and 6 per cent calling for a decade’s wait before another poll – The Scotsman, 2020

Gordon Brown says UK is ‘moving closer together’ despite talk of indyref2