A key question that flowed from the Supreme Court ruling on the government’s flagship deportation plan last week was this: will any asylum seekers make it to Rwanda by the time of the next election, which must be held by January 2025?

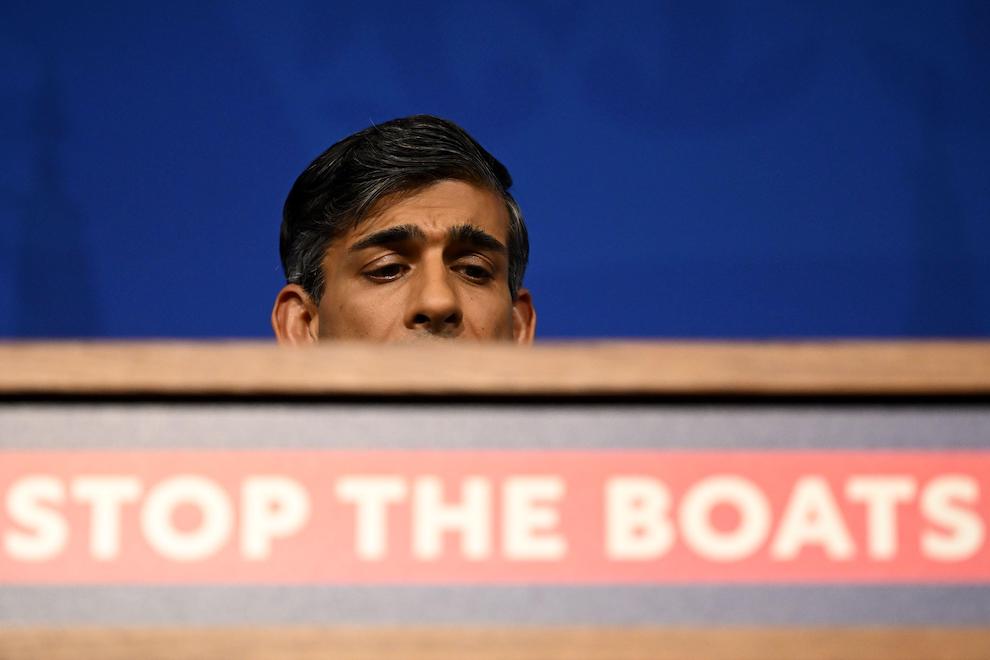

Animating this question is a future dilemma for Rishi Sunak — that, having overseen the Rwanda scheme for as many as two years by the next election, Keir Starmer will weaponise the scenario as proof of his failure to “stop the boats”. The media would be interested, too, in why quantifiably zero success has flowed from the government’s foremost “small boats” strategy.

And lo, the Conservative parliamentary party is now forwarding schemes that could see Sunak avoid this dire scenario. But perennial anti-ECHR antagonism and Suella Braverman’s “tests” aside, one intriguing idea doing the rounds is that the prime minister should embrace this political predicament and, contrary to his cautious instincts, turn it into the glue that cements a snap election campaign together.

In this way, an ally of Braverman briefed the Daily Mail before the Supreme Court ruled last week: “If the judges reject our plan, then at that point we have to go to the country. … We have to put our case directly to the people”.

Former cabinet minister Sir Simon Clarke has since further stoked such speculation: “We should be crystal clear: half measures won’t work”, he said. “We need the legislation that is brought forward to be truly effective, and if the Lords block it — let’s take it to the country”.

Clarke is far from a loyal supporter of the prime minister — but a possible hint as to Sunak’s view of a “stop the boats election” can be found in a recent media appearance. Asked on Friday if he would trigger a national poll if the Rwanda plan continues to be thwarted, Sunak declared: “Whether it’s the House of Lords or the Labour Party standing in our way I will take them on because I want to get this thing done and I want to stop the boats”. The answer, perhaps tellingly, seemed to be setting up a narrative around which an “stop the boats” election strategy could in time cohere.

But what would such hypothetical hinderers be mustering their powers to block — what, in short, is Sunak’s Rwanda “Plan B”?

The prime minister has signalled a dual-pronged approach following his Supreme Court snubbing last week. In a press conference on Wednesday afternoon, Sunak revealed his government would pursue a revised treaty with Rwanda to replace the current Memorandum of Understanding and address the concerns identified by the Supreme Court. And, on top of this, the government now plans to pass emergency legislation to decree to the courts that Rwanda is “safe” for all relevant purposes.

As things stand, the prime minister has yet to lay out the details of his emergency primary legislation. But the act of declaring Rwanda “safe” — any further attempts to override legislation through a “notwithstanding clause”, notwithstanding — would be hotly contested among parliamentarians, first in the commons and, second and more significantly, in the House of Lords.

With likely less than a year to an election, we have now entered the final session of parliament — it means the Lords is no longer merely a revising or delaying chamber. Rather, given peers can block legislation for up to a year under the terms of the Parliament Act 1949, a majority in House of Lords now has an effective veto on government legislation. The mere “ping pong” that accosted the Illegal Migration Act, as hostile amendments were summarily presented and disagreed with, would be nothing compared to the parliamentary impasse on any forthcoming Rwanda Is Actually Safe Bill.

And if the legislation does eventually pass, the government would likely face further legal challenges, both on the proposed Treaty and Sunak’s primary legislation.

Then, if Sunak’s “Plan B” progresses past this point, there is the outstanding question of whether the legislation and Treaty actually address the concerns the Supreme Court expressed last Wednesday.

In the end, what seems fundamentally clear is that Sunak’s updated Rwanda approach will continue to be contested — legally, politically and morally — all the way up to a general election.

But anytime during the above-described process, there will be the option for the prime minister to call off the lawyers and reach for the lectern. An address to the nation, after months of parliamentary and legal wrangling, would see the PM collect the Rwanda Plan’s acquired antagonists into one amorphous coalition. “Who runs Britain?”, the prime minister would ask as he identifies his opponents, by name or by insinuation, as the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lords, “lefty lawyers”, the Labour Party, Sir Keir Starmer, charities, campaign groups, etc.

“Get Rwanda done”, he would then bellow, lectern bruised from his enthusiastic thumping. An election would be called along these lines, some months before the expectation of his opponents.

Of course, the prima facie case for a “small boats” campaign is strengthened by the fact that this strategy template has, seemingly, succeeded before. Just four years ago, Boris Johnson’s focus on a “get Brexit done” pitch secured for him (alongside a constellation of other Corbyn-connected factors) an 80-seat majority.

Thus, a “small boats election” has for some time been sold as “Brexit part II” or “Brexit 2.0” by its backers in SW1. While there is no genuine connection between such a strategy and the 2016 referendum campaign to leave the EU, legal and political realities need not move as one. The Conservative Party will once again implore voters to “take back control”.

In fact, an illegal migration showdown with Labour — embracing British politics’ most comprehensible dividing line (pro-Rwanda versus anti-Rwanda) — could serve to reanimate the ghosts of 2019. Labour, alongside its ermine-clad allies and Sir Keir’s lefty lawyer pals (as the Conservative caricature contends), would once more be branded as frustraters of the “will of the people”.

Of course, in taking such a trenchant line, Rishi Sunak would likewise trigger some difficult realities. In such a campaign, public discourse would coarsen and anti-immigrant rhetoric, spotlighted by an election-readied media, would undoubtedly heighten. On top of this, there’s the quasi-constitutional consideration that single-issue elections do not stable governance make: a pattern that has played out over the preceding four years as the salience of a once-binding issue has inevitably softened.

But post-election scenarios are unlikely to be contemplated much in No 10 right now; and, in fact, other possible pitfalls of a “small boats election” are rather more tangible.

Firstly, there is the obvious question of whether Rishi Sunak is the right man to helm a “small boats”-focussed election campaign. Boris Johnson was able to make a “get Brexit done” campaign work because of his close association with and patronage of the “Leave” cause in 2016. But Sunak inherited the Rwanda deportation plan from Johnson and then-home secretary Priti Patel in October last year — and, since then, he has faced perennial criticism within his own party that he isn’t a true believer in the “project”. A true believer, the Conservative right consistently contends, would embrace a battle with the ECtHR.

But having taken up the “small boats”-stopping cause enthusiastically as PM, not least of all with his patronage of the Illegal Migration Act (which Braverman appears to have disowned in recent days), Rwanda could, I think, be sold as core to the Sunakian creed to the electorate at large.

A more significant problem for Sunak would be that — in so directly playing into the framing of his opponents with a “small boats election” — he opens himself up to criticism through the campaign and, in this way, prepares the ground for a revival of Reform UK.

The 2019 election saw the then-Brexit Party stand aside in the constituencies the Conservatives won in 2017. But next time around current Reform UK leader Richard Tice has vowed to take on the Conservatives up and down the country.

This is significant because a “small boats election” strategy would be targeted primarily at the group of voters who backed Johnson in 2019 but who have since become “don’t knows”.

However, this framing, crucially, ignores the Faragist factor. Reform UK could hence emerge as the natural receptacle for such voters’ discontents, given the party — unlike Labour — can criticise the PM for not being hardline enough.

What is more: in 2019 Johnson was able to corral Brexit-supporting sentiment behind him because he convinced voters that he, and he alone, could break the parliamentary deadlock. But the deadlock ahead of a “small boats election” would primarily be judicial, not parliamentary; it means Sunak will have to tie voters’ discontent directed at judges — and potentially at the Lords — to action at the ballot box. On this, one question would follow him throughout the campaign: “You already have a majority, what could you do after an election that your party could not achieve before?”.

There are other problems, too; because although Conservative strategists might want to construct their entire campaign around one subject, the British people will undoubtedly have other concerns. Indeed, while Sunak will try to point to the South Coast and consequently to his Rwanda plan, the vast majority of the Conservatives’ competitor parties will reject that framing altogether.

In light of this analysis, one must question whether Rishi Sunak has the political prowess to keep the spotlight fixated firmly on his pitch during an election campaign. Doing so would involve serious feats of political messaging given “asylum seekers and crossing the channels” figures just fourth when voters are asked to name the most important issues facing the country today, according to More in Common polling.

Worse still for the Conservatives, among “Loyal National” voters (socially conservative types who switched from Labour to the Conservative in 2017/2019), only 32 per cent highlight “asylum seekers and crossing the channels” as a key issue. This features third — behind the NHS (44 per cent) and the cost of living (74 per cent).

🧵 Taking the idea of a “small boats” election at face value. Why it’s a bad plan. Firstly while small boats is an important issue for the public it is dwarfed by cost of living & the NHS. A single issue election that ignored those concerns would appear deeply out of touch. pic.twitter.com/9XD2u9S2r4

— Luke Tryl (@LukeTryl) November 12, 2023

This data shows that the “Red Wall” would only be somewhat animated by a swinging “small boats election”. It begs the question: what will the other, larger half of the Conservatives electoral coalition in the “Blue Wall” make of the ploy?

Ultimately, that strategists are said to be contemplating a “small boats election” is probably itself highly revealing of Sunak’s lack of options politically. Such a strategy would see Sunak seize the moment, sure up elements of his party and, perhaps, stem an immediate sense of drift. But in the process he would invite upon himself a whole host of antagonistic forces — both party-political and electoral.

Thus, Sunak could in theory fight an early “small boats election” — but there is no reason to think it would prove more effective than any other strategy debuted, say, in January 2025.

So (very) ‘long’, prime minister: a January 2025 election has never looked more likely

Josh Self is Editor of Politics.co.uk, follow him on Twitter here.

Politics.co.uk is the UK’s leading digital-only political website, providing comprehensive coverage of UK politics. Subscribe to our daily newsletter here.