After all the rancour, partisan chicanery and accusations of a Speaker stitch-up, the House of Commons’ official record, Hansard, records soberly the outcome of the SNP’s opposition day debate on Wednesday as follows: “[Labour Party] Amendment (a) agreed to. [Motion], as amended, put and agreed to”.

Presiding over a chamber consumed by cantankerous din, deputy speaker Dame Rosie Winterton decided that Labour had won the day via “voice vote”. The question having been put, the “Ayes” rang louder than the “Nos”; the House, Dame Rosie decided, need not divide. As Conservative MPs protested, shadow commons leader Lucy Powell rose with a point of order: “The amendment in the name of the Leader of the Opposition was this evening passed unanimously”. A final self-satisfied point-score to round off a day of political gamesmanship.

Of course, Hansard does not nearly do justice to the depths the commons plunged on Wednesday afternoon. The debate was Westminster spectacle at its most spectacular. Unsurprisingly, as commentators searched furiously for recent precedent, Westminster’s collective memory of Brexit wrangling was invoked. Once more, a loose interpretation of commons procedure and irascible politicians had combined to create parliamentary anarchy.

But such parallels can be overstated. Whereas the commons Brexit debates from 2017-2019 reflected genuine divides within parliament and beyond, there was remarkably little to split to the content of the SNP motion and the government and Labour amendments on Wednesday. The SNP’s call for “an immediate ceasefire in Gaza and Israel” was met, for instance, with Labour’s call for “an immediate humanitarian ceasefire” and the government’s for an “immediate humanitarian pause”.

Still, as the commons descended into a “point of order” spiral on Wednesday evening, the spectre of an old Brexit force loomed large: that of former speaker John Bercow. Bercow, who presided over commons proceedings from 2009-2019, possessed a genuine penchant for constitutional innovation/vandalism (delete as appropriate). And the then-speaker’s professed aim to enable the House to express its will, despite its deep divisions, frequently came at the expense of the governing Conservative Party.

‘Bring back Bercow!’: Speaker faces Conservative and SNP anger over Gaza debate decision

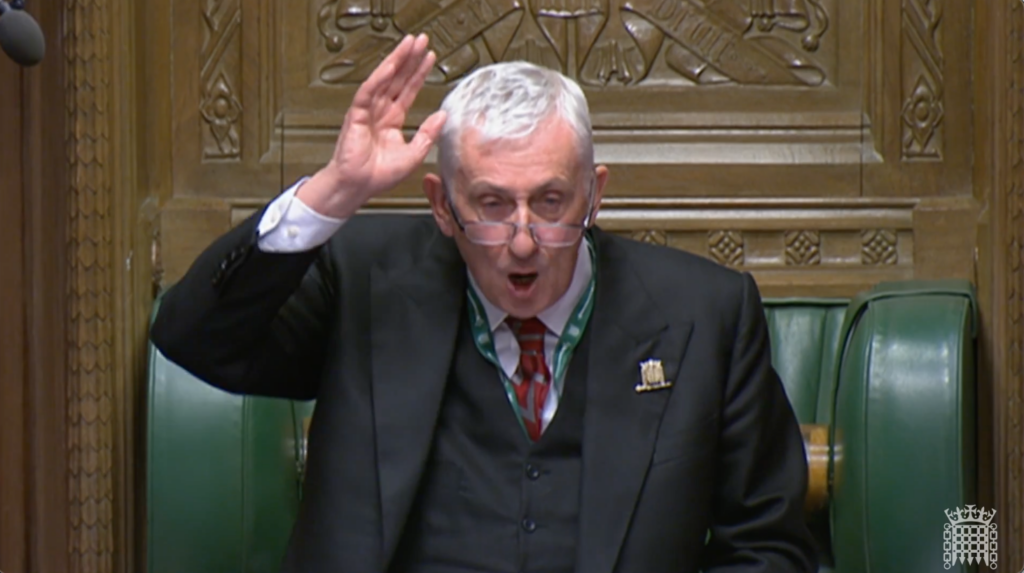

When Sir Lindsay Hoyle was elected speaker in 2019, Conservative MPs thought they had cast the excesses of Bercowism aside. This week, however, Hoyle sparked outrage that would make even Bercow baulk.

The speaker’s decision to dispense with precedent and allow Labour to move its amendment sparked a chain reaction that saw the original SNP motion on a ceasefire, after a series of twists and turns, effectively tossed aside. It was Hoyle, at the end of the day, who lit the fuse that saw the commons explode into acrimony.

Thus, for those Conservative and SNP MPs seeking to apportion blame, the speaker is the obvious target. 71 MPs have now signed an Early Day Motion (EDM) calling for Hoyle’s ouster; and SNP Westminster leader Stephen Flynn has signalled that his party will now act formally to remove the speaker.

Over 70 MPs back motion of no confidence in commons Speaker Lindsay Hoyle

Of course, by acting as he did on Wednesday, Hoyle thought he was solving problems, not creating them. Fearing for the safety of Labour MPs, he had opted to give the House the widest range of options on Gaza, allowing representatives to record their position on their own terms.

The problem for Hoyle is threefold: (1), his constitutional innovation on Wednesday contradicts the platform he stood on during the 2019 speakership election, when he promised to dully and duly act as a servant of precedent; (2), in saying his actions were driven by his “duty of care” towards MPs, Hoyle effectively conceded parliamentary business had been shaped by external pressure; and, (3), the ex-Labour MP’s decision, manifestly, saved Keir Starmer from experiencing the largest rebellion of his leadership.

But while much media attention has focussed on the future of the Speaker after the debate debacle on Wednesday — with hacks religiously refreshing the relevant EDM page — there is a larger, potentially more revealing story to tell here. The furore, simply, disguises difficulties for all parties at a crucial point in the electoral cycle.

Ultimately, the partisan dynamics that drove the Gaza debate did not cease when the Labour-amended motion was finally agreed to on Wednesday evening. The government, for instance, rather than support its backbenchers’ attempts to oust the speaker, has blamed the Labour Party, and Starmer specifically, for placing Hoyle in a bind. Addressing the House at business questions on Thursday morning, commons leader Penny Mordaunt accused Starmer of “damaging” the office of speaker. “I would never have done to him what the Labour Party have done to him”, she blasted.

Penny Mordaunt accuses Labour Party of ‘damaging’ the office of Speaker

Of course, Mordaunt’s address — part leadership pitch, part partisan tirade — speaks to the pressure on the Conservative Party to attack Starmer at every opportunity. Rather than turn on the speaker, whose ruling shaped the dire trajectory of events, she considered the broader symbolism. “We have seen into the heart of Labour’s leadership”, Mordaunt declared. “[Starmer] puts the interests of the Labour Party before the interests of the British people, and it’s the Labour leader that doesn’t get Britain”; in fact, “the past week”, the commons leader concluded, “has shown he is not fit to lead it”.

But the Conservative Party’s focus on Starmer may also serves to deflect from divisions in its own ranks. A series of Tory MPs were planning to vote for the SNP motion and Labour amendment on Wednesday — including many of those, such as William Wragg, who signed the EDM motion calling for Hoyle’s ouster. And, if former cabinet minister Kit Malthouse is to be believed, the number of pro-ceasefire rebels is “growing”. It was widely speculated on Wednesday that, if the commons did divide on this issue, enough rebel Conservative MPs could back the Labour amendment to force a government defeat. Mordaunt’s decision to pull out of the debate on Wednesday might have been informed by more than mere discontent at commons procedure.

‘Growing number’ of Conservative MPs back immediate ceasefire in Gaza

The anger emanating from SNP is a recognition that, to some extent, the party’s attempt to corner Starmer failed. An opposition day is party politics at its purest; a non-governing party is granted commons time to hold a symbolic vote on its terms, typically, with a view to splitting an electoral adversary. Liz Truss’ downfall, remember, was preceded by the Labour Party’s canny decision to hold an opposition day debate on fracking; the threat of a significant Conservative rebellion, in the end, prompted a botched response from the whips’ office in what amounted to Truss’ final act as PM.

Note also the opposition motion that the SNP did not move on Wednesday, relating to £28 billion of investment in green energy. This was a day, plainly, about putting Labour in the most uncomfortable position possible. And Flynn would have succeeded, too, if it wasn’t for Hoyle’s decision on amendments. Labour-SNP electoral competition will be a significant feature of the 2024 general election — particularly in Edinburgh and Glasgow, areas with high Muslim populations. That, in essence, explains why the SNP’s ire is directed at the speaker.

Is Keir Starmer sleepwalking into a Conservative trap on Labour’s £28bn green pledge?

And what of the Labour Party? Well, its significant divides over the situation in Gaza will not have been healed by Hoyle’s decision on amendments; rather, with both the speaker and commons leader Mordaunt intimating that time could be made for a debate rerun, Hoyle may have merely offered Labour a brief reprieve. Moreover, with the Conservative Party’s rhetoric escalating, senior Labour Party figures could — after all — have questions to answer regarding their involvement in discussions with the speaker.

In the end, the noise that enveloped the debate on Wednesday and its aftermath can, in part, be attributed to the pressures that befall each party at a crucial point in the electoral cycle. Ultimately, the key takeaway from this especially unedifying episode of UK politics is that we are now in an election year — and the temperature is rising. Expect many more such showdowns, on this issue and others, before polling day finally arrives.

Josh Self is Editor of Politics.co.uk, follow him on Twitter here.

Politics.co.uk is the UK’s leading digital-only political website, providing comprehensive coverage of UK politics. Subscribe to our daily newsletter here.