Last month, I reflected on the May local elections, analysing what the notional results at the constituency level from those elections told us about the state of the Conservative Blue Wall in the south of England.

I had intended to write this follow up article on what events in Chesham and Amersham told us about the region, expecting a reduced Conservative majority and a nice swing to extrapolate. But Thursday’s nights results have changed those plans.

The result in Chesham and Amersham is notable in its own right.

This is the first time that this seat has ever had a non-Conservative MP since its creation in 1974. It is also the first time the Conservative vote has ever dipped below 50% in the constituency. The previous highest ever non-Conservative vote was 31.2% (in Feb 1974 and 1983), but in this by-election the Liberal Democrats scored 56.7%, with the Conservatives reduced to 35.5%. In turn, their 16,000 vote majority has been exchanged for an 8,000 vote Lib Dem majority.

Within the bounds of local anger over HS2 and the Lib Dem by-election machine, a Lib Dem victory by a couple of thousand votes seemed possible. However, the scale of this victory suggests that there is more at play than merely local factors.

Once again it points to the Blue Wall realignment.

Much like in my previous article, in this analysis I have taken the trends seen at this latest by-election and applied them across the same Blue Wall area in the South of England that I used last month.

Previously this blue wall region did not actually include Buckinghamshire (and thus Chesham and Amersham itself), and so to keep the comparison clear I have used the same counties considered previously.

Moreover, to allow for the fact that this was a by-election, with the potency for voters to vent extra anti-government sentiment, I have scaled down the size of the effect.

Rather than use the 25.2% swing achieved by the Lib Dems in Chesham and Amersham, which would turn practically the whole region orange, I have considered the effect of a swing that was first at a quarter, and then at a half, of the level just experienced in Chesham and Amersham.

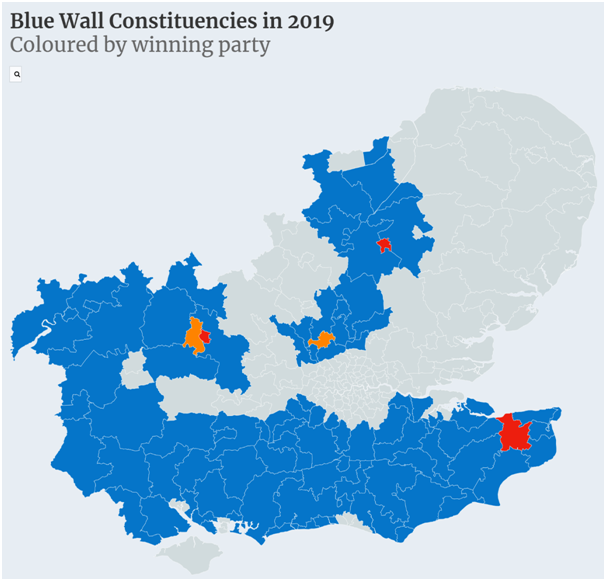

As detailed in Figure (1), in the 2019 General Election, the Conservatives won 82 of the 87 seats in this area of the south of England, with Labour taking 3 and the Lib Dems 2.

Figure 1

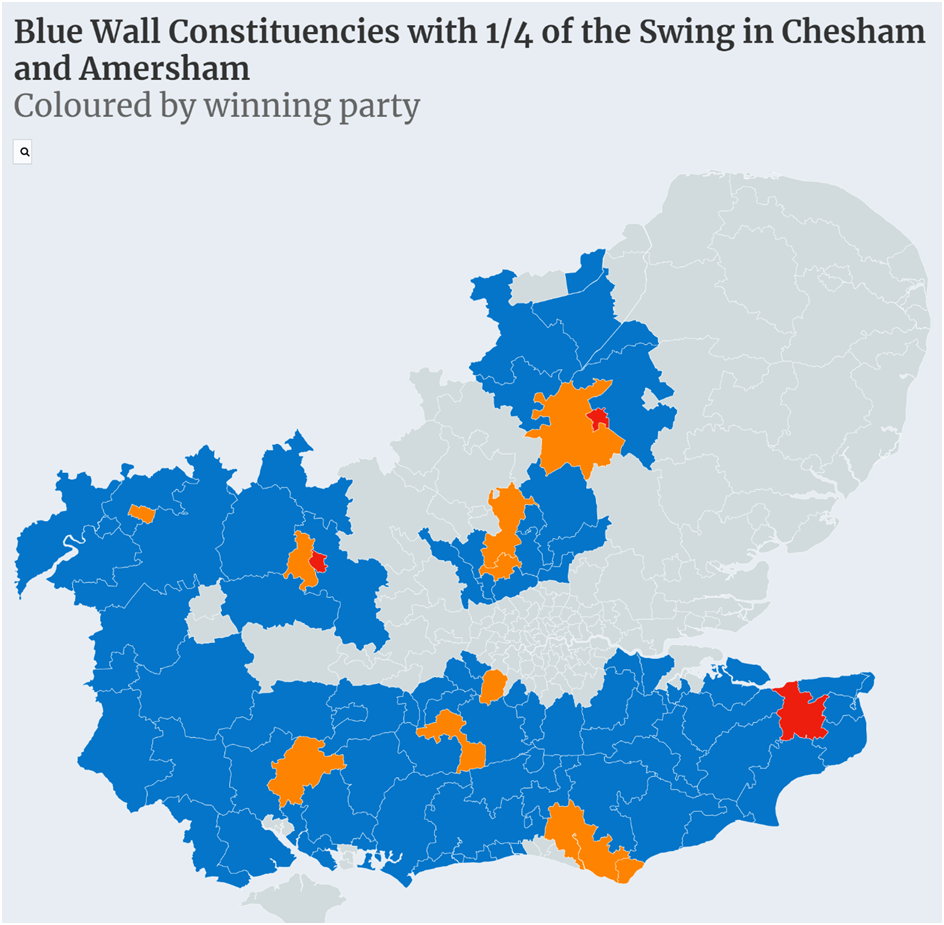

If only a quarter of the swing seen in Chesham and Amersham was replicated by the Lib Dems in a General Election then, as per Figure (2), the map already starts to look very different. The Conservatives drop down to 74 (down 8), Labour remain on 3 still, and the Lib Dems emerge on 10 (up 8).

Figure 2

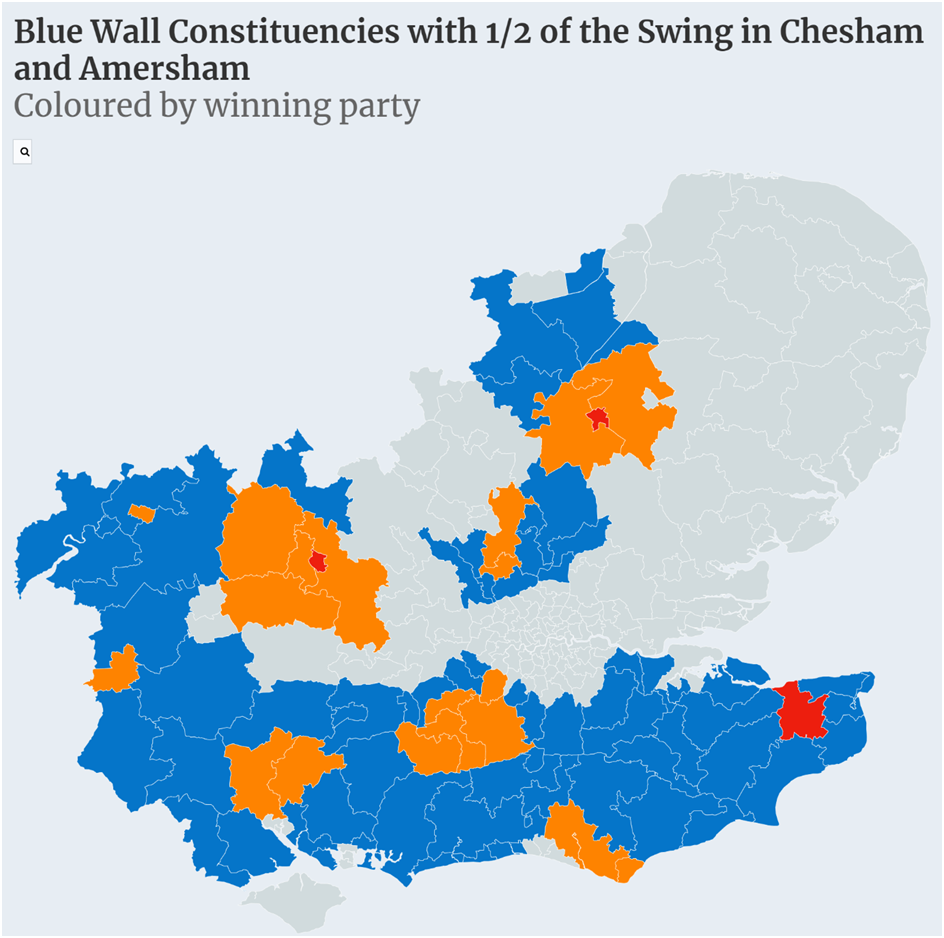

If half the swing achieved in Chesham and Amersham on Thursday was applied across the region in a General Election then the map starts to change rapidly, and dangerously, for the Conservatives in the South East of England. As per Figure (3), this sees the Conservatives reduced to 65 seats (down 17), Labour still on 3 and the Lib Dems up to 19 (up 17).

Furthermore, in this scenario, there would be two particularly big scalps for the Lib Dems to take. Both the former and current Foreign Secretaries, Jeremy Hunt and Dominic Raab, would lose their seats to their Lib Dem challenger.

Figure 3

Together, this analysis continues to highlight the threat that the Tories are facing, and how their current strategy of looking to gain votes off Labour in the Red Wall has the potential to alienate their traditional voters. If left unchecked, they risk losing scores of seats to the Lib Dems, even without suffering a swing anything close to that which we just saw in Chesham and Amersham.

As I said in my previous article, if the Lib Dems could succeed in significantly cutting the Conservative majority in Chesham and Amersham, then this can be taken as a sign of growing Liberal Democrat strength in the region. The Liberal Democrats have gone beyond that.

This is the first substantial brick in the blue wall to be dislodged.

Of course, in the past the Lib Dems have won numerous safe seats from the Conservatives in by-elections, which in the case of Christchurch and Newbury back in the 1990s, were safer even than that of Chesham and Amersham.

What makes the current developments so interesting is that, in the light of the recent by-election in Hartlepool, and the potential one still to come in Batley and Spen, events in the south of England are diverging so markedly from the concurrent developments in the north.

Once again, it suggests that as the Conservatives are building their red wall in the north, it is shaking in the south.

We are not in the territory of saying that the Blue Wall itself will deprive Boris Johnson of a majority; regardless of what happens elsewhere, this will take some time yet.

However, given the margin of the Liberal Democrat victory we saw on Thursday night, it would be no surprise if the Blue Wall rises up against Boris Johnson far sooner than previously thought.