Overview

Currently, 26 Bishops from the Church of England have an automatic right to sit in the Upper Chamber of the British Parliament (‘the Lords Spiritual’).

The Church of England fiercely defends the continuing presence of its Bishops within the House of Lords.

Critics on the other hand, comment that this is potentially the most anachronistic element of the British constitution. Today the United Kingdom is the only Western democracy that gives religious representatives the automatic right to sit in the legislature.

Indeed, there are just three countries in the world where “clerics” remain involved in law making: the Vatican, Iran, and the UK.

What do House of Lords Bishops Do?

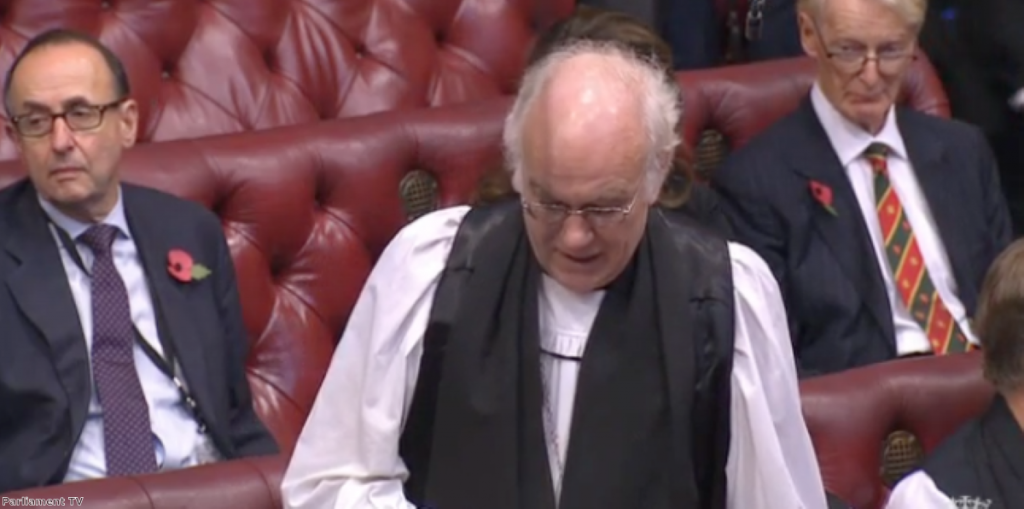

At the start of each day’s sitting in the House of Lords, one of the Bishops reads out a prayer in the Chamber. This ensures that at least one Bishop attends the House of Lords on every day that it sits.

Prayer reading aside, the Church of England’s Bishops then perform the same role as all other Members of the House of Lords. They scrutinize legislation, ask questions, make speeches, and crucially, vote.

Within the House of Lords, the Bishops have been likened to operating as a political party. They are not the same as the independent cross benchers. Just like a party political group in the House of Commons, the Lords Spiritual sit in their own defined position, as one block to the right of the throne. Individual Bishops are each allocated to cover and lead on particular policy area for the Church of England.

The Bishops have what they call their own Convenor. He or she fulfils a role somewhat equivalent to that of a political party’s Chief Whip, The main purpose of the Convenor is to represent the Bishops in their discussions with the other political parties, and to organise the Bishops within Parliament. The Bishop’s Convenor is appointed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, and in 2021 the post was held by the Bishop of Birmingham.

Which Bishops sit in the House of Lords?

The 26 most senior Bishops in the Church of England are the ones that take up the Church of England’s seats in the House of Lords.

Apart from the two Archbishops (of Canterbury and of York) and the Bishops of Durham, London and Winchester, the seniority of Bishops is measured in the number of years they have held office as a Bishop within the Church.

If a Bishop who sits in the House changes his title, he or she retain the right to sit in the House of Lords, as that right is conferred on the individual and not on the bishopric itself. Lords Spiritual are though required to retire from the House of Lords at the age of 70.

Normally, Archbishops are given a life peerage on retirement. There is though no automatic right to a life peerage on retirement for any other Lord Spiritual.

The average attendance rate of the Lords Spiritual (ie: the 26 Bishops who sit in the House of Lords) is approximately one third of the rate of the average Peer within the Upper Chamber. This is said to be a reflection of the fact that Bishops also have responsibilities within the General Synod and across the diocese in which they practice and serve.

A study of the voting behavior of the Bishops within the House of Lords over a sustained period of time indicates that they appear careful not to rile the Government of the day. Although they do not always vote together as one totally solid block, past analysis of the voting behavior of the Bishops has shown them to vote, both for and against the government, in almost equal measure.

Should the Church of England’s Bishops continue to sit in a modern Parliament?

Separate to the wider case that is made for House of Lords reform, those opposed to the automatic presence of a Bishop within the United Kingdom Parliament, typically make three points.

Firstly, it is argued that providing one particular religious group (the Church of England) with such a preferential and automatic status in the country’s legislature, is totally inappropriate in a society which is now so multi-faith.

According to the polling group, Com Res, in 2017 just 6% of the population were practicising Christians. The Church of England’s regular weekly attendance is now less than one million (1.5% of the population). This is not significantly advanced from those attending weekly mass in the Catholic Church or Muslim prayers, and yet these other faith groups lack any such automatic representation. For the Church of England’s Bishops to be afforded their preferential status is cast as being at odds both with modern Britain, and the affirmation of a plural society.

Secondly those coming from a non faith perspective, argue that it is actually totally inappropriate for any faith group to be afforded a role in the legislature. Aside from more general concerns about the formal mixing of politics and religion, it is noted how religion as a whole is no longer the dominant force in everyday life. The 2018 British Social Attitudes Survey showed how the majority of the UK population (52%) defined themselves as non religious.

Thirdly, those from both a multi-faith and non religious perspective, take issue with the Church of England’s claim that it is uniquely qualified to provide ethical and spiritual insights on behalf of the general population. Not least given the various religious and non religious viewpoints now at play. Humanists UK have branded the Church of England’s claim as both ‘factually incorrect’ and ‘offensive’, asserting that, ‘people from many walks of life, and from many religions and none, are at least equally qualified if not more so – for example, moral philosophers and experts in medical ethics’.

The History of the Bishops in the House of Lords

Those arguing that the Church of England’s 26 Bishops should retain their role in the Upper Chamber, point to the fact that the Church of England is the ‘Established Church’, and they refer to the historical contribution of the Bishops.

Bishops have been a feature of the House of Lords for over 700 years.

The role of Bishops in the Palace of Westminster dates back to the feudal and medieval days of the 14th Century. Prior to Henry VIII dissolving the monasteries between 1536 and 1540, the Lords Spiritual (the ‘Bishops’) represented the majority within the House of Lords.

The Bishops were then briefly removed from Parliament in 1642 as a consequence of the Bishop Exclusion Act passed during the midst of the English Civil War. However the Bishops soon returned en-masse after the passing of the 1661 Clergy Act. Indeed during the eighteenth century there was a block of over 200 Bishops within the House of Lords.

In 1847, the number of Bishops in the House of Lords was cut to 26 as a consequence of the Bishopric of Manchester Act. That reform, some two hundred years ago, came at a time when the Prime Minister was himself sitting in the House of Lords. This remains the last time that the constitutional position of the Bishops was altered. Since then, nearly two hundred years have passed, universal suffrage has arrived and the hereditary peerage has been abolished.

In 1985 the Church of England’s Bishops saw off an attempt by the then Conservative MP, Richard Holt, to reduce their numbers to 14. Mr Holt’s plan involved replacing 9 of the Church of England’s Bishops with representatives from other faith groups.

When the House of Lords underwent structural reform in 1999, namely to alter the position of hereditary principle and reduce the size of the Upper Chamber, the Bishops again successfully evaded reform.

The same happened again in 2009, when further reform then saw the Law Lords disqualified from sitting or voting in the House of Lords.

The Church of England claims its Bishops fulfill a vital role in the House of Lords. Richard Chartres, the former Bishop of London, has claimed that the Bishops are “in touch with a great range of opinions and institutions”.

What do the public feel about Bishops in the House of Lords?

If someone is looking for a contested political issue, but one on which there appears to be the strongest public agreement, the case being made for the removal of Bishops from the House of Lords may well be it:

– Just 8% of people believe that Bishops should retain their seats in the House of Lords [Source: YouGov, 2017].

– Religious representatives are the public’s least favoured candidates for appointment to the House of Lords. [You Gov, 2003].

– 62% of Britons say there is “no place in UK politics for religious influence of any kind” [Source – Com Res – 2016]

– 70% of Christians believe it is wrong for Bishops to have reserved places in the House of Lords [Source – ICM Research – 2010]