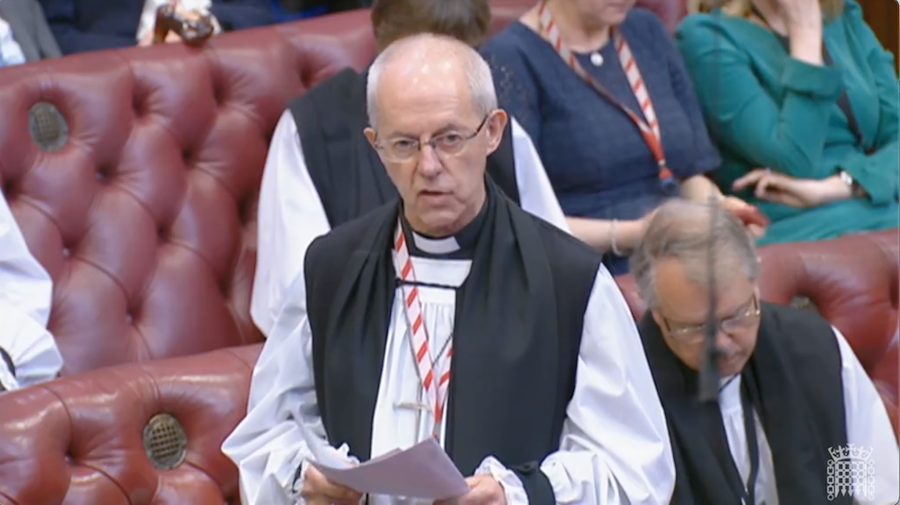

Since Wednesday, a further name has been added to the eclectic catalogue of “lefty lawyers” and political activists blamed for thwarting the government’s small boats agenda. The new individual of concern is, of course, the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby — fresh from crowning a new monarch on Saturday. Addressing Britain’s assembled nobles in the House of Lords, he branded the government’s latest legislative punt on small boats “isolationist, … morally unacceptable and politically impractical”.

Truly gone are the days when the Church of England could be described as the “Tory party at prayer”.

But Welby’s righteous reprimand had been anticipated by home secretary Suella Braverman, and the government hustled on Wednesday to grasp the news agenda. In a joint article for the Times with new justice secretary Alex Chalk, Braverman urged Britain’s unelected peers not to deny the “will of the people”.

Constitutionally, of course, when Welby pronounces in the House of Lords he is not speaking for the “people” per se. As a member of the Lords Spiritual, his is a legitimacy derived from a higher authority, and his interventions are hence reserved for moments of particular moral indignation. Crucially, Welby’s is not a voice of permanent opposition — and so that he chose to speak at all on Wednesday was immediately politically potent.

But the substance of his speech did not disappoint either.

In a blistering attack upon Sunak and Braverman’s plan, the most Rev. Welby said the bill — which includes measures to offshore the processing of asylum-seekers in Rwanda — would not fulfil the prime minister’s promises, ignored the key causes of the movement of refugees and could break the system of international cooperation which promises to help those fleeing war, climate disaster and conflict.

So moral considerations aside, Welby was clear that the bill would prove useless even per the standard the government has itself set. Indeed, from the outset the Archbishop willingly conceded that Britain “need[s] a bill to stop the boats … a bill to destroy the evil tribe of traffickers”; this was no naive, tofu-devouring liberal talking. But, he added: “The tragedy is that without much change, this is not that bill”.

The politics of this is tricky for the government. Diocesan discontent, encapsulated by Welby’s two-pronged assault on the bill’s moral and substantive aspects, is clearly a deeply discomfiting public blow for the PM on what is already fiercely contested territory.

In time, Welby’s moral guidance may serve to empower those already implacably opposed to the legislation and, potentially, some wavering Conservative backbenchers who abstained — rather than voted against — the bill during its commons stages.

Welby, crucially, also committed himself to improving the bill. He told the House that, despite his concerns, he would not be supporting the amendment tabled by the Liberal Democrat peer Lord Paddick, a former senior police officer, that would block the legislation as a whole. “It is not our duty to throw out this bill” the Archbishop attested, amendments readied. Still, that the Archbishop was joined in his condemnation by a host of Liberal Democrat and Labour peers indicates that this stage will be dominated by the government’s critics.

As for the bill’s supporters, their arguments focussed not on its merits in “stopping the boats” per se but on the potential constitutional impropriety of the unelected chamber standing in the government’s way. Lord Dobbs, a former adviser to Margaret’s Thatcher government, rubbished Panick’s fatal motion as “quixotic and deeply unconstitutional”.

Ultimately, Wednesday’s archepiscopal intervention points to the ping-pong to come as the Lords and commons battle over the illegal migration bill’s detail. And after Rishi Sunak’s balancing act through the bill’s commons stages — which saw the Conservative party right appeased by an amendment on ignoring ECHR interim injunctions — this time hostile Lords will look overwhelming to moderate the bill on areas including modern slavery and combatting people traffickers.

During the bill’s commons stages, the implications of the legislation for victims of modern slavery was the primary focus of former PM Theresa May. While she ultimately chose to abstain on the legislation, she told the commons of one government amendment introduced in committee: “[Amendment 95], far from making the provisions better for the victims of modern slavery, makes it worse. … It’s hard to see this government amendment as an example of good faith”.

On Wednesday, Theresa May was watching from the Lords’ gallery and was reportedly shaking her head during minister Lord Murray’s opening speech.

Where next for ‘stop the boats’?

So as we enter this new, uncertain phase of the illegal migration bill’s parliamentary life, it is worth considering how the key actors want to frame the debate.

Suella Braverman has made it plain that this Lords stage will be a battle between “the people”, for whom she presumes to speak, and the unelected peers. Welby conceives of the debate differently — and in his capacity as a member of the Lords Spiritual has chosen to focus on his view of the bill’s moral failings.

In the end, the debate will likely come down to a series of amendments, tabled by critical Lords, and eventually sent back to MPs for further consideration. The government will work to reject the changes, falling back on the rhetorical wrecking strategy of the “will of the people”. May may make noise, but ministers know the Lords amendments can at best delay the bill’s steady progress.

But perhaps this is what Braverman and Sunak want. In framing the debate as “the people” versus the Lords, the government can now not only dismiss amendments on procedural — rather than substantive — grounds, but use the attempts at moral moderation as a lightning rod through which to channel their grassroots’ anger.

Indeed, the best-case scenario for the government right now may be a long delay in the upper chamber before royal assent is granted by (a probably unsympathetic) King Charles. From here, the legislation will be faced by a series of legal challenges in both domestic and international courts. The “will of the people” calling card will be tabled at every turn.

And soon enough it will be election time.

The government would probably quite like to run in 2024 on the much-foretold, soon-to-be-ripe fruits of the illegal migration bill. After thirteen years in government, ministers will always be more comfortable talking about future legislation as opposed to the party’s record.

Welby’s intervention, therefore, sets up a further period of frustration for the bill’s advocates which the government will surely look to exploit. Indeed, as Welby’s House of Lords homily pointed to, what may be a larger problem for the government is not that the bill will not pass — but that it does and does not work.

Keeping the electorate in suspense on small boats might just be the way forward for Sunak as he navigates increasingly turbulent political waters. A long Lords delay now will at least excuse a lack of delivery later.