Like dominoes, Scottish giants tumble.

First fell Nicola Sturgeon, who declared her shock abdication at Bute House just over one month ago. Then deputy first minister John Swinney, who has swivelled around the apex of Scottish politics for decades, followed suit. Now Sturgeon’s husband Peter Murrell, who held his role as Party CEO for 24 years, has been forced to quit. He followed Sturgeon’s closest adviser Liz Lloyd and media chief Murray Foote to the exit door — officially ending one of the most effective political partnerships in Western democracy.

But the personality changes, punctuated by brief periods of mourning, tell only a partial story.

The true measure of the SNP’s political difficulties is the complete and utter breakdown of the party’s internal norms over the past month. The iron discipline, prosecuted by the untouchable Murrell-Sturgeon duopoly, has unravelled spectacularly into an openly hostile succession crisis. The yellow-on-yellow side-swiping, the allegations of sleaze and incompetence — it all points to a deep sense of derailment in party ranks.

Last week’s turmoil over membership numbers is a case in point. It followed a string of denials from SNP HQ that large numbers had quit the party either over gender reforms, a lack of progress on independence or to join Alex Salmond’s Alba Party. Still, the party would not publish membership numbers until after the race to replace Sturgeon was complete.

But following much internal pressure, for which the leadership contest proved a conduit, the SNP leadership caved. It was revealed that just over 72,000 members are eligible to vote in the contest to replace Sturgeon as party leader. It meant numbers had fallen by more than 40 per cent from their 2019 high of 126,000.

It prompted the immediate resignation of SNP spinner Foote who said he had been misled when he rubbished reports that SNP membership had slid as “drivel”. The implication was that Murrell had misled him, and the party CEO followed shortly thereafter.

Everything had gone “spectacularly wrong”, cried Michael Russell, Murrell’s replacement as SNP CEO, to the BBC over the weekend. This concession, of course, begs the question: what might the SNP’s recent trajectory have looked like had things gone right?

Did it really have to end like this?

When Nicola Sturgeon announced her resignation, the outgoing first minister likely foresaw a leadership campaign characterised by various shades of continuity. Angus Robertson, the constitution secretary at Holyrood and close Sturgeon confidant, was immediately ordained as frontrunner and was heralded as the first minster’s most likely heir. The nat baton would hence be passed by conventional means: via effective coronation.

Robertson’s rivals would be found wanting on various fronts. Finance secretary Kate Forbes would not survive the initial media onslaught on her social conservatism. Ash Regan or Joanna Cherry, heading the gender rebel faction, would prove far too divisive among the party’s activist base. And squeezed by establishment support for Robertson, Humza Yousaf would prove unable to explain away his record in government. Other potential runners and riders in Màiri McAllan and Neil Gray would ultimately back the new face of the ancien régime.

The short contest, concluded in a matter of weeks, would then allow for Sturgeon’s heir to challenge the UK government’s veto of the Gender Recognition Reform Bill. It would provide for some much-needed political momentum, continuing the more aggressive tilt against the UK state begun by Sturgeon and uniting the SNP faithful against Westminster’s egregious excesses. The former first minister would watch proudly from Holyrood’s backbenches.

Of course, the big-picture story from the last few months of Scottish politics is that things have not played out quite how Sturgeon hoped or expected.

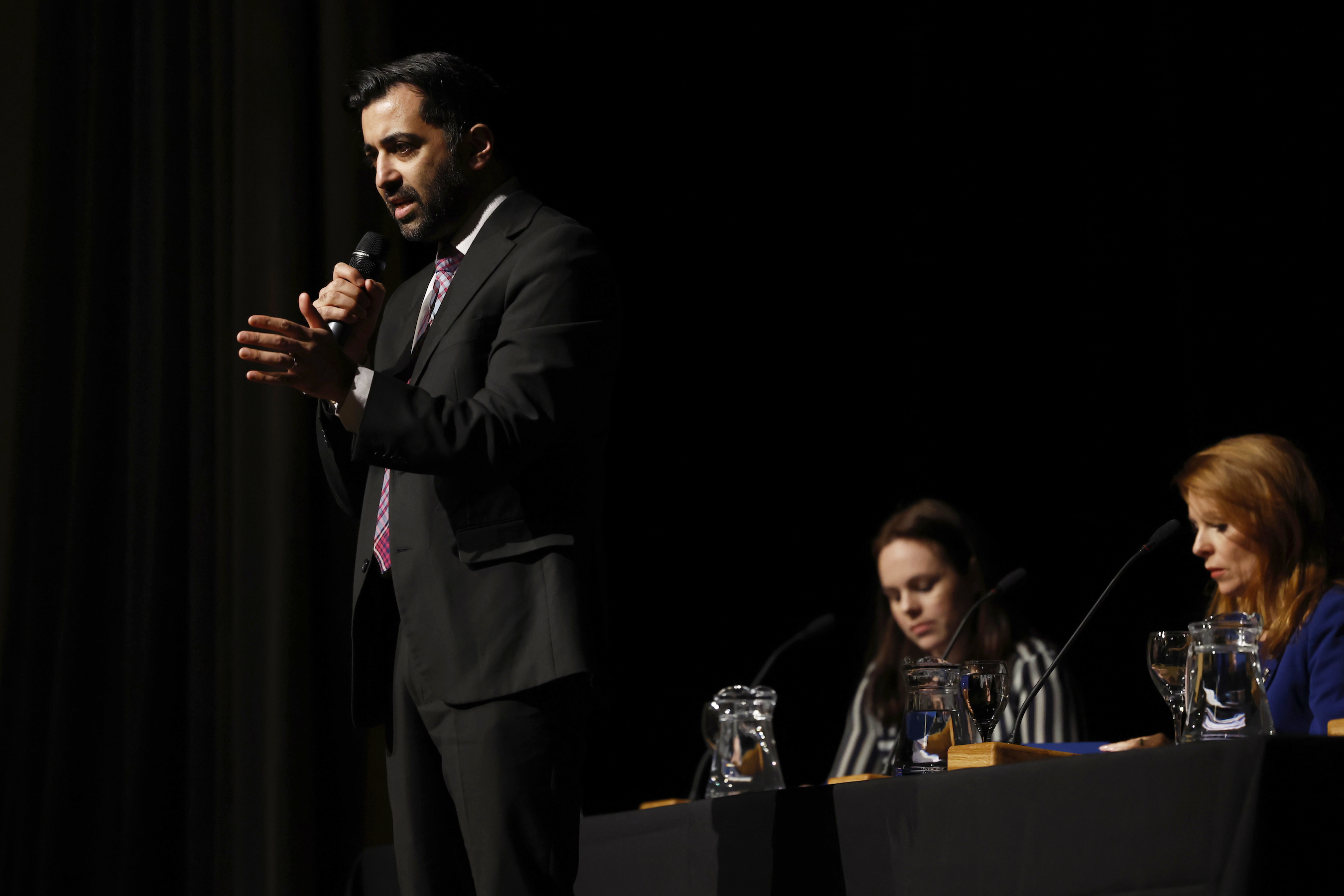

After Robertson declined to stand as frontrunner, Humza Yousaf was shunted to the front of Sturgeon’s disputable heirs. As court favourite and establishment cypher he benefited from the backing of large numbers of MPs and MSPs, but his ministerial record on transport, justice and health was wide open for attack.

Yousaf’s chief challenger, Kate Forbes, has run on a soft change platform, using Yousaf as a springboard to launch broader attacks on the SNP’s record in government. In her leadership pitch, Forbes has been relatively clear that she would remould the SNP as an ideologically “lite” party in aa bid to widen independence’s appeal across the classes and sectional interests. Her recent commitment to pursue “smaller, focussed government to … accelerate reform” is a key signal she would remould the party’s social democratic profile as FM.

Then there is Ash Regan, who has the most radical position on the question of Scottish independence of the three. She has said that if pro-independence parties win more than 50 per cent of the vote at either the next Westminster or Holyrood election, the Scottish government should immediately begin negotiations to trigger independence. However, Regan is yet to comprehensively outline how she would bend the UK state to her undoubtedly steely will. Rather, her campaign has been at its most effective in its aggression towards the “party establishment” — to which she views Yousaf as irremediably in tow.

Tellingly, Murrell’s resignation has been viewed as a win above all for Regan. It was her open letter, also signed by Forbes, that had requested that up-to-date membership figures be released. In doing so, she calculated that gunning for the top of the party machine, seen as in cahoots with Yousaf’s campaign, would strengthen her offering as an outsider.

Now both Forbes and Regan have claimed that the leadership process has been so completely mishandled by the party, that some members may now regret having backed Yousaf. Regan has called for members to be permitted to “update their vote” online following the chaos.

Regan’s positioning was strengthened further after Nicola Sturgeon’s strategic policy and political advisor Liz Lloyd announced she, too, would be resigning from government. It came after Regan had raised concerns that Lloyd had been providing advice to Yousaf and broken party rules in the process. A spokesperson for the Scottish government denied that rules were broken, but Lloyd quit her job anyway.

In the end, it has been Regan — the race’s unknown, unpredictable outsider — that has most fundamentally shaped the SNP’s post-Sturgeon political territory.

Heading into the race, Regan was of course regarded for her maverick qualities. She entered the public eye after resigning from the Scottish government to vote against its gender reforms, immediately setting herself up as a thorn in the side of the party establishment. But to the surprise of many, Regan has worked carefully to not run her campaign along such divisive gender reform lines.

Her political strategy has been to exploit activists’ grievances with the party’s perceived power-hoarding, weaponising discontent with the cosy household politics of the Sturgeon-Murrell duopoly. It may not win her the contest — nor many fans among the establishment’s elected entourage — but she has instituted a sense of profound culture shock in SNP ranks. Thanks to her, Sturgeon’s successor will need to immediately reconcile their vision to a platform of change in party HQ.

Regan’s anti-continuity positioning has been bolstered by the rumours surrounding SNP party finances. The leadership race has seen further scrutiny applied to the case of the “missing” £600,000 that was raised from party members, through crowdfunding. According to the Financial Times, donors claimed hundreds of thousands of pounds given during the 2017 referendum appeal and a subsequent 2019 fundraising effort were spent by the party on other things. A long-running police probe has been rumbling on in the background to determine what happened to the money. In an interview with Sky News on Monday, Sturgeon denied that she had heard whether the police want to interview either her or her husband.

This fiasco, like that over party membership, has highlighted once more the potential pitfalls of Yousaf’s “continuity” pitch. The health secretary’s perceived proximity to the SNP powers-that-be has emerged as a serious political problem for the leadership contender.

Now somehow, out of all this, one of Yousaf, Forbes to Regan will have to reunite their party. If it is Yousaf who emerges on top, which remains the race’s most likely outcome, his opponents headed by Regan will almost certainly cry foul. It surely means that the SNP’s arc of instability crisis is far from its apex.

Sturgeon’s successor will need to prove that they can be more than a caretaker as the party continues its process of savage soul-searching. But in the end, public appetite for a more meaningful change in Bute House, stemming from the psychodramatic chaos of this leadership election, may prove difficult to ignore.