Some say that reshuffles, if executed well, can sharpen and re-energise governments, set ambitious agendas and boost a prime minister even if their authority is ailing. Rishi Sunak is not one of those people.

The prime minister has been presented with opportunity after opportunity to shake up his top team. But, at every turn, he has chosen caution.

Of course, some intent was displayed in February when Sunak seized upon the resignation of Nadhim Zahawi as party chair to rejig Whitehall as he broke up the department for business, energy, and industrial strategy and apportioned various chunks among already-serving cabinet ministers. The subsequent shifting even saw a promotion for up-and-comer Lucy Frazer, albeit to the relatively junior cabinet post of culture secretary.

Since then, the resignation of Dominic Raab in April as deputy prime minister and justice secretary — like Zahawi under the cloud of scandal — only sanctioned a slight shift in personnel. Oliver Dowden, a loyal ally (note the phrase), was awarded the former post, while Alex Chalk, a loyal ally (ibid), won the latter.

And Thursday’s reshuffle was a variation on this same technocratic theme.

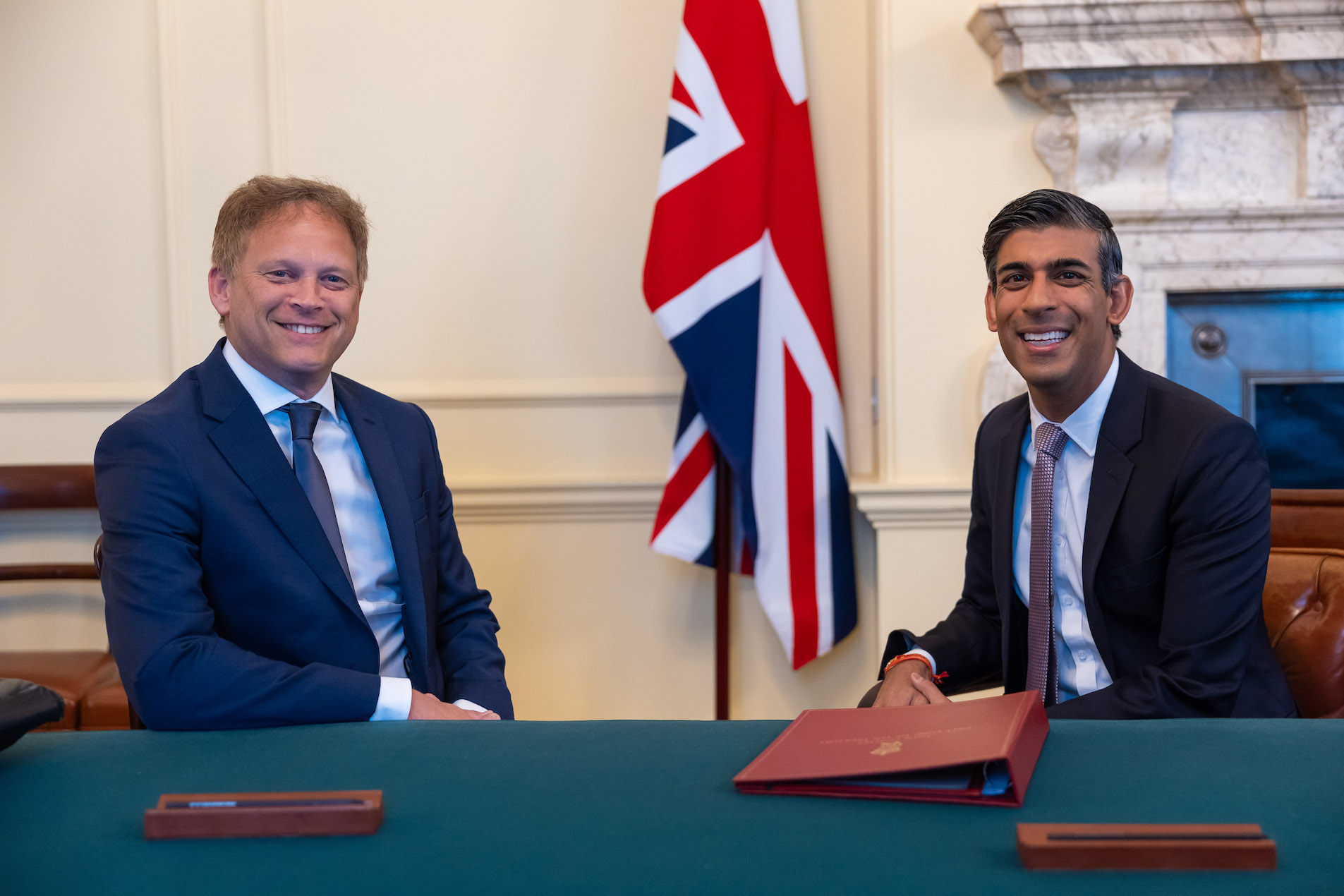

Ben Wallace, having signalled his intent to take leave of his defence brief in July, was finally allowed to resign. It prompted a sideways shunting for perennial seat warmer and loyal Sunak ally, Grant Shapps. Shapps’ move meant a more junior figure in Claire Coutinho, a (you guessed it) loyal ally, was vaulted upwards.

In truth, it was another surgical incision of a reshuffle; and thus you might confidently conclude that there is little to be gleaned from a shift so slight.

Necessity, as ever, was proving the mother of Sunak’s desperate attempts to avoid reinvention.

But when Sunak’s three mini-reshuffles are viewed in full, we begin to see hints of what our prime minister values in his chosen lieutenants.

Sunak’s first and most obvious desired trait is, yes, loyalty. Perhaps particularly after the resignation of Nadine Dorries redrew attack lines in the Conservative party, Sunak has once again shown that he craves a top team he can trust.

Last October, Sunak was constrained in his cabinet choices by the complex politics of his post-Truss inheritance. Having agreed on the need for party unity and some semblance of ministerial continuity, he buried his instinct for appointing allies and unveiled a “cabinet of all the talents”. But now Sunak is slowly walking back to first principles. It means the cabinet’s increasingly scant manifestations of the Trussite hangover — such as Therese Coffey at DEFRA — should probably fear for their jobs should Sunak tilt towards a less timid switch-up in time.

Of course, Grant Shapps has been a doggedly loyal lieutenant for the prime minister, eagerly parroting government talking points in his jobs as business secretary and energy security secretary. That he has proved happy to shift sideways this week, having already channelled so much energy into the net zero brief, is further evidence of his lackey-like manner.

And, in doing so, Shapps replaces Ben Wallace — a onetime Boris Johnson stalwart whose popularity in the Conservative party allowed him to interpret the convention of cabinet collective responsibility remarkably loosely. What is for certain: the new defence secretary is not going to fall out with his cash-conscious boss on defence spending.

Claire Coutinho, too, is a staunch loyalist having served with Sunak previously as a special adviser at the Treasury, then as his PPS in parliament. The two are said to be close personally, and importantly they seem at one on policy (like Sunak, she is an ardent Brexiteer).

Coutinho will be expected to adopt the government’s fine line on net zero — as Sunak pivots from environmental to electoral incentive on the policy post-Uxbridge — while all the time balancing the views of “green Tories” and the Net Zero Scrutiny Group. Of course, having worked with Julian Smith when he was chief whip during the peak of Theresa May’s Brexit tumult, Coutinho will be no stranger to the shifting factional dynamics of the party she serves.

But, returning to my first point, the most obvious lesson from this reshuffle is that Sunak has not yet shaken his cautious political predisposition. Indeed, promoting David Johnston, who backed Nadhim Zahawi in last summer’s leadership contest, to Coutinho’s old job will be a signal that the PM is not yet ready to ditch his doubled-edged “government of all the talents”.

Nonetheless, it is a well-understood fact now that the prime minister has been preparing to become more election-ready in recent months.

The summer recess, divided up into select media weeks, was thought to be the PM’s chrysalis of reinvention as he emerged, new-and-improved, in sharpened attack mode.

However, if commentators were counting on the PM throwing caution to the wind in early September, we may need to find a new talking point. Sunak’s evolution from tinkerer-in-chief to rabid attack dog may yet be rather slower than first suggested.

After Thursday, a future, larger-in-scope reshuffle is now spoken about for October — after the party’s annual conference but before the November King’s Speech.

However, there will be questions now as to how well this week’s mini-reshuffle has prepared the ground for its grander, more politically pointed, October successor. Surely Shapps won’t move again in a further rejig; one would likewise imagine that the recently reshuffled Alex Chalk, Oliver Dowden, Lucy Frazer and Claire Coutinho will also stay put.

But this presents a problem: how “big” can an October “big bang” reinvention be if certain ministers are essentially immovable — lest the Conservative party face further accusations of excessive ministerial churn?

What does Sunak want?

There is, of course, the case for the defence.

Sunak knows that “reset” rumours tend to only emerge when a government, as then-composed, appears dead in the water electorally. Acting on such chatter, therefore, may tighten the feeling of fin de régime that embalms his government.

Moreover, the PM knows that reshuffles are risky. Significant cabinet reshuffles inevitably create enemies and, if recent Conservative psychodrama is anything to go by, enemies no longer tend to slink quietly into the political wilderness.

The last thing Sunak will want is overlooked or disposed opponents wandering around the conference fringe (à la talismanic troublemaker Michael Gove under Liz Truss) making headlines and sapping momentum.

In sum, Sunak currently views mini-reshuffles, preceded by ministerial resignation, as a means to further inspire a veneer of competence in and around his government. He wants people who can pick fights on the media round while staying composed under tough questioning. Such figures, Sunak presumes, will give him the best chance of passing the tests he set himself in January.

But the appearance this all creates is of a tinkerer-in-chief, shuffling deckchairs and ducking opportunities to pursue a more overtly political government. Observers, both internal and external, may begin to conclude that Sunak is either, (1), not ruthless enough or, (2), so unbelieving in his own ability that — even after 10 months as PM — he does not think he can set an agenda in government without inviting the ire of his party.

And in the end, Sunak’s pitch at competence matters little if he fails to deliver on his pledges. In truth, come Conservative conference, Sunak could be setting himself up for the worst of both worlds as party opponents lament both a lack of vision as well as a lack of results. Down the line, one wonders whether Sunak will rue not making a mark on his party sooner.

It may also be the case that the select “loyalists” left on the backbenches — someone like Liam Fox who was passed up as defence secretary in this instance — may become noisier in time. The longer Sunak leaves any cabinet-led “reset”, the more and more active the decision becomes to decline the services of his backbench backers.

Ultimately, if politics is about making the most of one’s opportunities — especially for a PM under such concerted internal and external pressure — after so many false start reshuffles, one inevitably begins to wonder whether Rishi Sunak has what it takes.