The Safety of Rwanda Bill, which returns to the House of Commons this week, must be one of the strangest laws ever proposed by a modern British government. The legislation takes us into a topsy-turvy world of Alice in Wonderland politics where nothing is ever quite as it seems.

After all, the Safety of Rwanda Bill was invented to respond to the UK Supreme Court finding about the unsafety of Rwanda’s asylum system.

The Rwanda plan is that Britain pays Rwanda so it can remove asylum seekers to the African country to make their claim there instead. The legal verdict was that such a scheme could be lawful in principle with a country that had a safe asylum system. However, the Supreme Court found the evidence compelling that the Rwandan asylum system was so systemically flawed – with few decision-makers trained to make asylum decisions – that it would be unsafe for Britain to remove people there.

The UK government’s official position is that it accepts the UK Supreme Court decision (though its Rwandan partners denounced it as an unfair political decision of the British courts). Nevertheless, the UK government says that the two governments have worked diligently to remedy the defects that led to the judgment.

The initial Memorandum of Understanding is now a fully-fledged Treaty. Some specific concerns – that Rwanda has removed asylum seekers unsafely back to their country of origin – are addressed by promising they can only send people back to Britain.

Yet if the Treaty had succeeded in making Rwanda safe, there would be no need for a Safety of Rwanda Bill. The government could proceed with removal notices – and anticipate that the UK courts would reverse the judgement, and now declare Rwanda safe enough for removing asylum seekers there.

No Albanian Safety Bill was necessary to enact the returns deal with Albania – because it is a lawful policy in principle and practice. There was no need for legislation insisting that the courts must turn a blind eye if it is not safe.

With Rwanda, the effect and purpose of the Rwanda Safety Bill is to direct the courts that they must find Rwanda a safe country for removals from Britain – and must do so without considering the substance of whether it is safe or not.

The UK government last week updated its Country Information Report on Rwanda, describing it as “a relatively peaceful country” with some issues with human rights. This coincided with Burundi closing the border with Rwanda, accusing the Rwandan government of funding the Red Tabara rebel group who killed soldiers and policemen near the Congo border in December. The elections in DR Congo are heightening tensions. President Tshisekedi’s campaign rhetoric escalated last week into a threat to declare war on Rwanda and even “march on Kigali” – arguing retaliation could be justified by the Rwandan regime backing the M23 rebel groups.

If the Safety of Rwanda Bill is enacted into law, one consequence is that Rwanda must always be considered safe by the UK courts, whatever might change in the future. Not even the clearest proof of breaches of the Treaty would change that. Not even a conflict on the border, or indeed a military coup, civil war or (God forbid) another genocide in Rwanda itself would make Rwanda unsafe in British law, however unsafe it might become in reality.

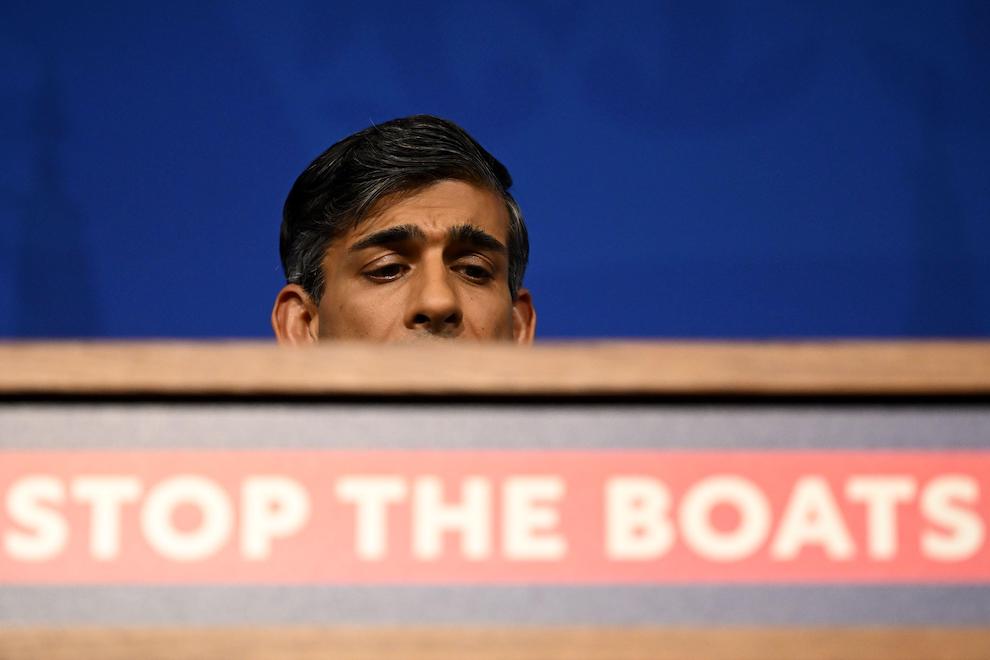

What gets curiouser and curiouser is that the Rwanda Safety Bill blocks the UK courts from considering the legality of the policy while it maintains the oversight of the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights. This is despite the prime minister’s soundbite of choice being “I won’t allow a foreign court to block flights taking off”.

The UK Supreme Court is, as its name signals, a UK court. Removing the role of the UK courts serves a political purpose – making sure the public argument is with an international court, rather than a British one. But it does sound like the opposite principle to that suggested by the prime minister.

The government says that it is confident that the Rwanda Safety Bill complies with international law – although the first thing the Bill contains is a declaration by the Home Secretary that he cannot say it is compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. The Bill gives the Attorney-General the right – but the Government argues that the Bill does not necessarily breach international law since she might not use the power which she is granted.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty says to Alice in Through the looking glass, “it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” The Rwanda Safety Bill looks like a clear attempt to put that Humpty Dumpty principle onto the statute book.

To do so, the legislation needs to pass both houses of parliament. While the focus this week is on the prime minister’s battles with his own backbenchers, the government faces a different and potentially more difficult challenge to persuade the House of Lords that it has no alternative but to accept these Humpty Dumpty rules too when it comes to the role of the courts and breaches of international law.

Back in Wonderland, Alice replies to Humpty Dumpty: “The question is whether you can make words mean so many different things?”

Humpty Dumpty retorts: “The question is which is to be master – that is all”.

Politics.co.uk is the UK’s leading digital-only political website, providing comprehensive coverage of UK politics. Subscribe to our daily newsletter here.