Nicola Sturgeon’s resignation on Wednesday has elicited a series of theories about how the high-riding, poll-topping first minister was brought before Bute House to announce her abdication.

An exhaustive post-mortem is well underway, with supporters and political foes alike proffering their assessment of the rights and wrongs of Sturgeon’s political dynasty. The prevailing reading is that Sturgeon’s gambit to treat the next general election as a “de facto” referendum was a step too far for some in the SNP. Sturgeon’s response to her supreme court snubbing last November was to double down on the rhetoric and whip up the grassroots — it was arguably an unsustainable strategy for a party which has no guaranteed means of delivery.

MPs and MSPs in marginal seats, too, argued that running the next general election on a one-line manifesto, at a time of international war and a cost of living crisis, profoundly misread the political scene. They worried for Scotland’s independence cause and, perhaps more pertinently, their own political careers.

Then there was the furore of Sturgeon’s gender self-identification policy. In December, the first minister thought she had achieved some legislative finality on the issue, with her Gender Recognition Reform Bill passing Holyrood by 86 votes to 39. But the cries of “shame!” from the public gallery, which prompted the sitting to be briefly suspended, hung in the air ominously. The politically fraught row over a transgender prisoner which followed saw the doom loop over the gender self-ID debate spiral further. Buffeted by a series of separate crises, there is little surprise Sturgeon was running out of gas.

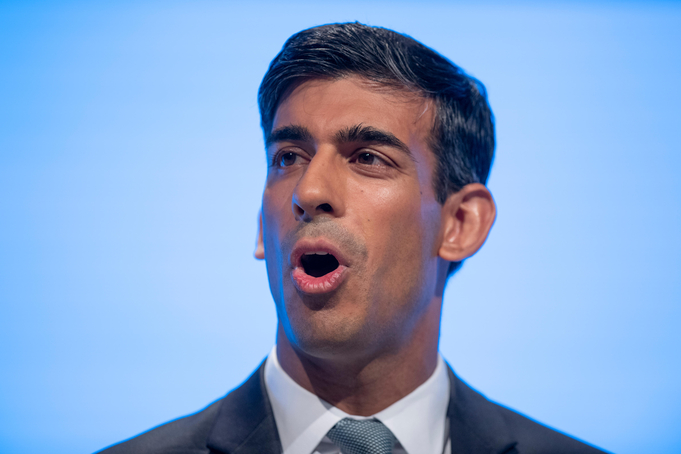

However, there is another character in the chronicles of Sturgeon’s decline and fall, one not known for his ruthlessness, but whose presence in Scotland’s self-ID drama is undeniable. That man is UK prime minister and Section 35 triggerer-in-chief, Rishi Sunak.

As prime minister, Sunak was the final authority on the decision to trigger Section 35, blocking the GRR Bill on the grounds that it impinged on the operation of the UK-wide Equality Act. The move — the first in devolutionary history — meant that Holyrood’s presiding officer was prohibited from submitting the bill for Royal Assent.

Sunak’s decision inflamed tensions in the SNP, angering pro-self-ID insiders who thought the Holyrood vote would consign infighting in the past. Indeed, Sunak’s intervention was a signal that the debate was stepping up a gear at a serious moment of political vulnerability for Sturgeon.

It presented the first minister with a challenge: would she now take the case to the Supreme Court, potentially leading to another embarrassing loss, while further distracting from the SNP’s independence push?

The answer was prevarication — in any case, it wasn’t long before Scottish politics was consumed by an equally fractious debate over a transgender prisoner.

Sunak’s allies will say there was no good fortune to his Section 35 decision: he had simply chosen to amp up the pressure on Sturgeon at the perfect moment. The first minister, in the end, was no match for Westminster’s reserved powers.

Of course, one can debate to what degree Nicola Sturgeon’s handling of the self-ID debate contributed to her resignation – and Sunak’s role in the drama was probably reactive at best.

Moreover, rather than benefit the Scottish Conservatives’ political prospects, the debate may have bolstered Scottish Labour’s pitch north of the border. In the end, Sturgeon’s downfall may lead to a rise in Anas Sarwar’s fortunes, not Douglas Ross’.

But Sunak will nonetheless be flaunting the fall of the Union’s most formidable foe to his critics. While the blow itself may not have been fatal, the fact that the prime minister has outlasted at least one political opponent will be cause for much cork-popping in No 10. In triggering Section 35 Sunak can point to an example of potential ruthlessness; it is therefore a small win for Sunak, but right now even small wins are few and far between for the besieged PM.

In the end, Sunak’s intervention may be treated as one of the very minor benefactors of the perfect storm which blew Sturgeon to Bute House that momentous day.