What is extremism?

In broad terms, extremism is the vocal or active opposition to conventional values. This is often fuelled by a narrow belief which can steer an individual into terrorism.

Having updated its definition in March 2024, the UK government defines extremism as “the promotion or advancement of an ideology based on violence, hatred or intolerance, that aims to

- negate or destroy the fundamental rights and freedoms of others; or

- 2undermine, overturn or replace the UK’s system of liberal parliamentary democracy and democratic rights; or

- intentionally create a permissive environment for others to achieve the results in (1) or (2).”

Terrorism is an example of extremist conduct intended to advance a political, religious, or ideological cause. The process by which someone comes to adopt extremist views is known as radicalisation.

Any belief or view is vulnerable to extreme interpretation: political standpoints, religious interpretation, social causes are among the most common.

The 2013 Government report ‘Tackling Extremism in the UK’ stressed the necessity of limiting extreme conduct in all forms, stating, “The UK deplores and will fight terrorism of every kind, whether based on Islamist, extreme right-wing or any other extremist ideology.”

Extremism in the UK

Extremism in the UK dates back to the 1800s. The focus of terrorism in the UK over the last fifty years has been dominated by the conflict in Ireland, and more recently, by the threats from Islamic terrorism and far right terrorist groups.

Between 1970 and 2016, the UK experienced 5,227 terror attacks, which resulted in 3,420 deaths. Among the deadliest since the turn of the Century have been the London Underground Bombings of July 2005 and the Manchester Arena Bombing of May 2017.

Within Europe, recent terrorist incidents include the Nice Bastille Day attack 2016 and the Berlin Christmas market attacks of the same year.

Islamist extremism

On 11th September 2001, Islamist extremists hijacked four planes which were flying across the United States of America. Two of the planes were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Centre in New York, one was flown into the US military headquarters in Washington DC, and the fourth crash-landed on a field in Pennsylvania. With nearly 2,977 fatalities, this terrorist attack remains one of the deadliest incidents to have hit the Western world. There has been a marked rise in Islamist extremist terrorist activity around the world in the subsequent two decades.

Islamist extremism is not to be confused with traditional Islamist practice. Islamist terrorists are motivated by an extreme and distorted interpretation of Islam which typically seeks Islamic revolution through enforcing Sharia law, often through use of violence.

Far Right Extremism

Far Right extremism relates to those with extreme far right and white supremacist views. Far right extremists advocate the use of violence and mass murder typically in pursuit of an apocalyptic race war. They promote their ideology online, including on social media.

In June 2016, public awareness of the threat of far right extremism increased considerably after the murder of the Labour MP, Jo Cox in the West Yorkshire village where she was due to hold a constituency surgery. Thomas Mair, who held extreme far right view was found guilty of her murder and sentenced to life imprisonment with a whole life order.

Between 2017 and 2020, the police intercepted eight terrorist plots related to violent right-wing extremist ideologies. This evolving threat is evident in radicalised young people. According to the Home Office, 10 out of the 12 under 18s who were arrested for terrorism in 2019 were linked to extreme right-wing ideology.

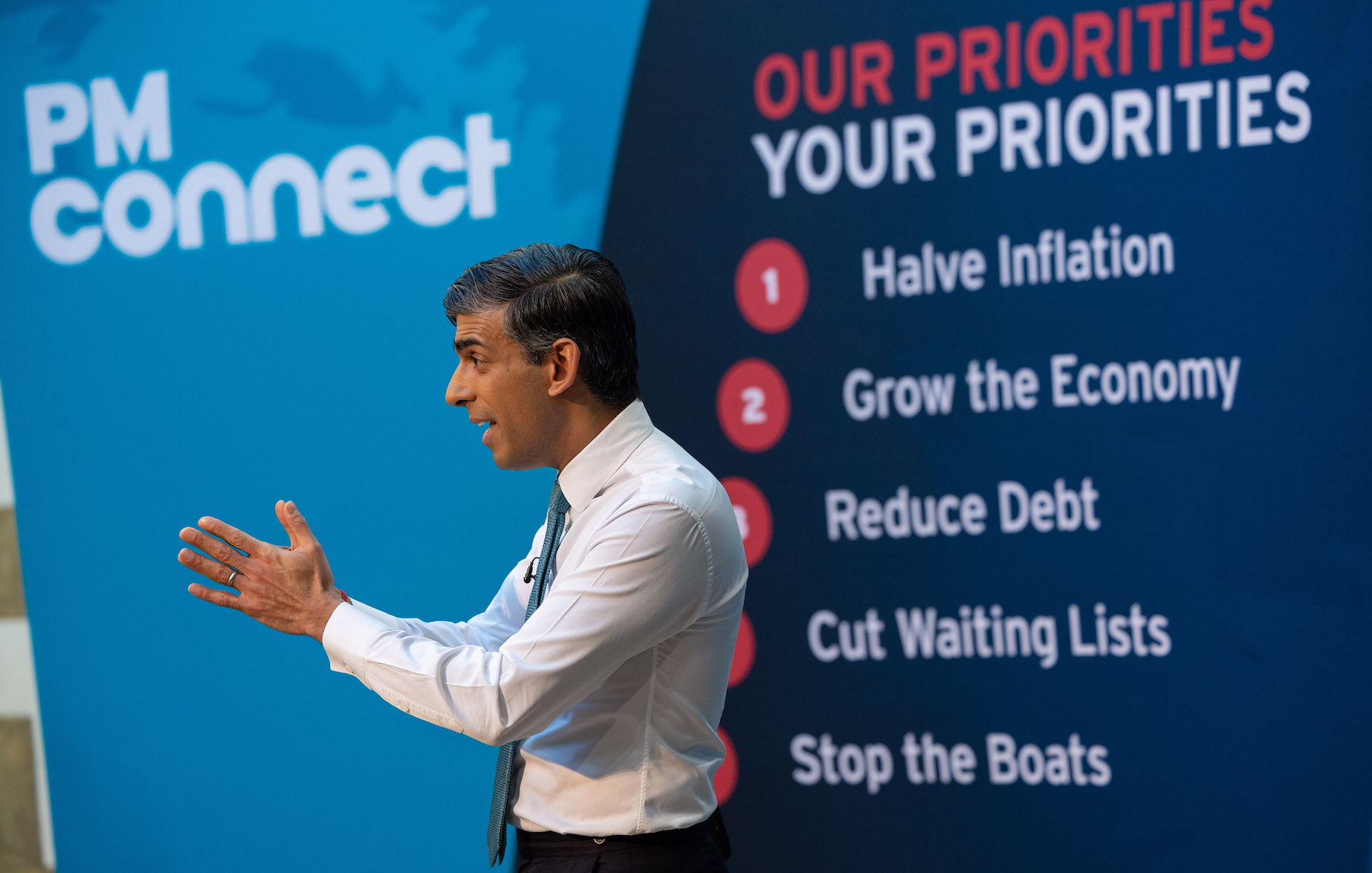

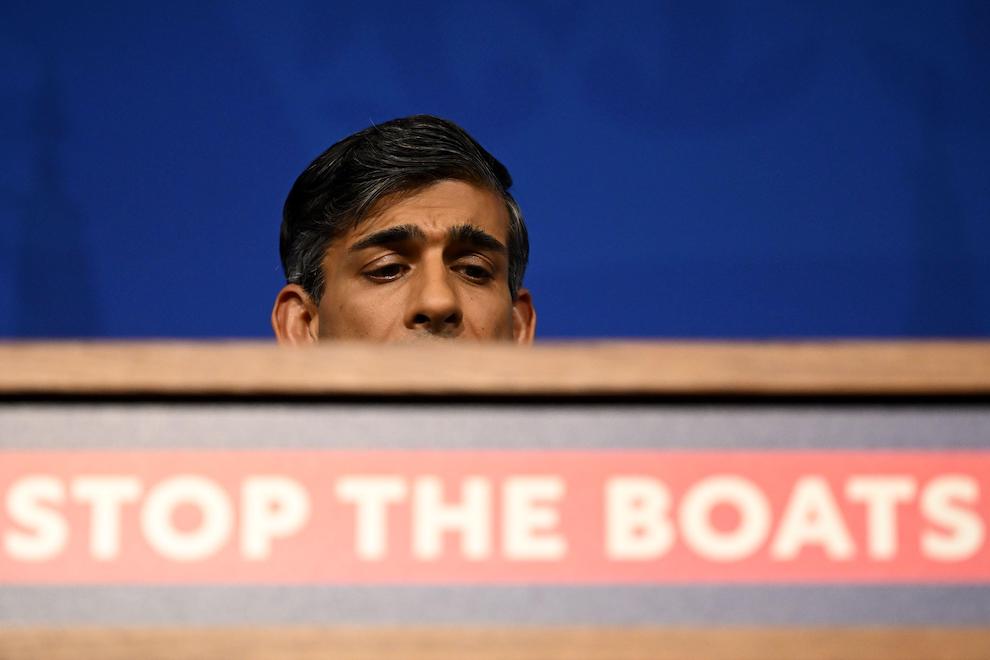

The government’s new extremism definition

Announcing the new definition in March 2024, communities secretary Michael Gove said the previous extremism definition, in place since 2011, was “insufficiently precise” and had been “insufficiently policed”.

The government previous position defined extremism as “vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs”.

According to the government’s new definition, groups and individuals labelled extremist will have the right to seek reassessment and submit new evidence to a review.

If they still disagree, they can challenge the government’s decision through a judicial review of the decision.

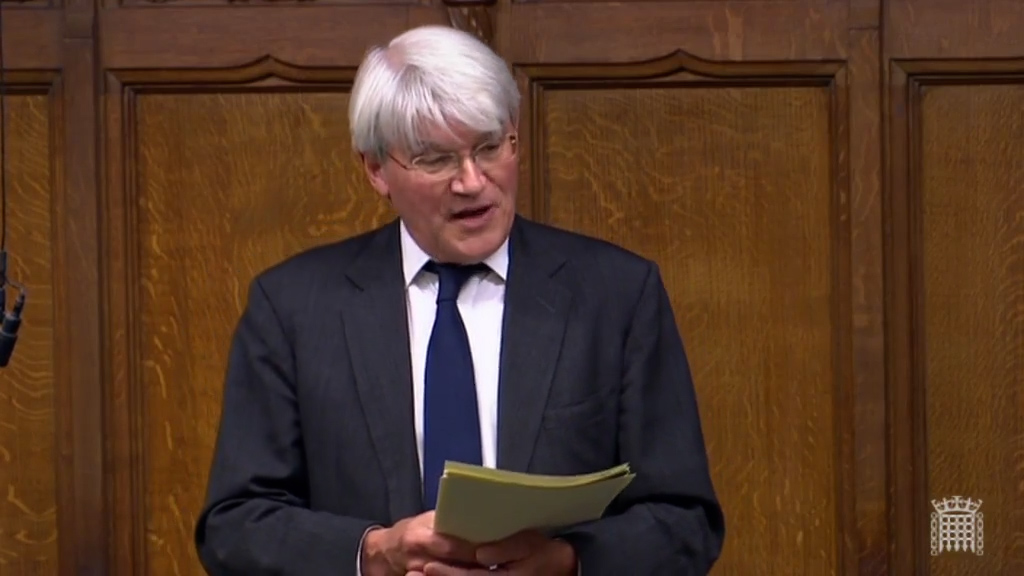

Speaking in the commons, he said the British National Socialist Movement and Patriotic Alternative would see their activities assessed against the new definition.

He said the groups “promote Neo-Nazi ideology” and were “precisely the type of groups about which we should be concerned”.

He also named the Muslim Association of Britain, Cage and Muslim Engagement and Development (MEND) as organisations that “give rise to concern for their Islamist orientation and views”.

He defined Islamism as a “totalitarian ideology” that calls for “an Islamic state governed by sharia law,” and should not be conflated with Islam itself.

After Gove made a statement on the government’s new definition of extremism in the commons in March 2024, former Home Office minister Robert Jenrick said he feared it would not do enough to “tackle the real extremists,” or do enough to protect people who are “simply expressing contrarian views”.

Fellow Conservative MP Mariam Cates said it could see “gender critical feminists” labelled as extremists, and end up “chilling speech of people who have perfectly legitimate, harmless views”.

Meanwhile, deputy Labour leader and shadow communities secretary Angela Rayner said her party would “challenge and probe” the government’s new definition and pressed Gove for more detail on how it will “work in practice”.

Countering extremist groups in the UK

In the UK, the 2001 twin towers attack marked a heightened alert level to international terror threats.

However, in 2017, a Parliamentary briefing paper on counter-extremism emphasised the rising threat from “homegrown” terrorists; that is, those whose perceptions have been radicalised on British soil.

Extremism Online

The internet has grown to be the most common platform for radicalisation. Exploiting the anonymity of online forums and social media sites, vulnerable people are targeted by extremists wanting to recruit individuals to their cause.

Following the terror attacks in London and Manchester, the then, Prime Minister Theresa May reiterated the need to “regulate cyberspace to prevent the spread of extremist and terrorism planning.”

A 2012 Report by the House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee called on the government to work with internet service providers to remove all extremist material online. According to the Home Office, following the introduction of the Prime Minister’s Extremism Task Force in 2013, approximately 18,000 pieces of online terrorist propaganda were successfully removed.

The Government also pledged to work with internet companies to limit the availability of extremist material which is hosted overseas.

Extremism in schools and universities

Young people are particularly vulnerable to the influence of hateful extremism and, over the past decade, have been subject to increasing attempts of radicalisation through exposure to narrow ideologies.

The government has focused in particular on the risk that extremist preachers have been known to exploit secondary and higher education systems as platforms for spreading their beliefs.

In July 2013 the government’s counter-extremism strategy committed to working with universities most susceptible to radicalisation, providing specialist training and educating around the early signs of extremism. The following year, the government enforced robust policies to ensure that all UK schools were supporting fundamentally British values while protecting them from extreme or anti-establishment voices. This is part of an ‘act early’ approach, particularly in relation to vulnerable children.

In July 2015, this ‘prevent strategy’ was enforced further by placing legal responsibility on schools and universities to “show due regard” to the need to prevent a young person from being drawn into terrorism.

Extremism in Prisons

A 2018 report by the Council of Europe branded prisons “a breeding ground for radicalisation and violent extremism”.

In the UK, the government has stressed its concern that prisons house some of the most dangerous extremists in society. Criminals who are already predisposed to violent behaviour face higher and more acute risks of radicalisation.

In response to this, the government has recruited Muslim Prison Chaplains to lead one-to-one sessions challenging prisoner views rooted in, or tending to, extreme perceptions of Islam.

Laws on correspondence have been tightened to prevent extremist material from entering prisons, and prisoners are more closely monitored ahead of release.

Proscribed Groups

The Home Secretary is also able to lay proscription orders before Parliament in order to ban certain groups under the Terrorism Act (2000). Proscription makes it a criminal offence to be a member of, or invite support for, a particular proscribed terrorist group, with those found guilty facing up to 10 years imprisonment.

In 2020 there were 76 proscribed groups in the United Kingdom. These predominately comprised Islamic and white supremacist terror groups. A further 14 organisations in Northern Ireland remain proscribed under previous legislation.

A liberal approach to extremism is taking shape – but will the govt let it survive?

Prevent anti-extremism strategy creating ‘suspicion in the classroom’