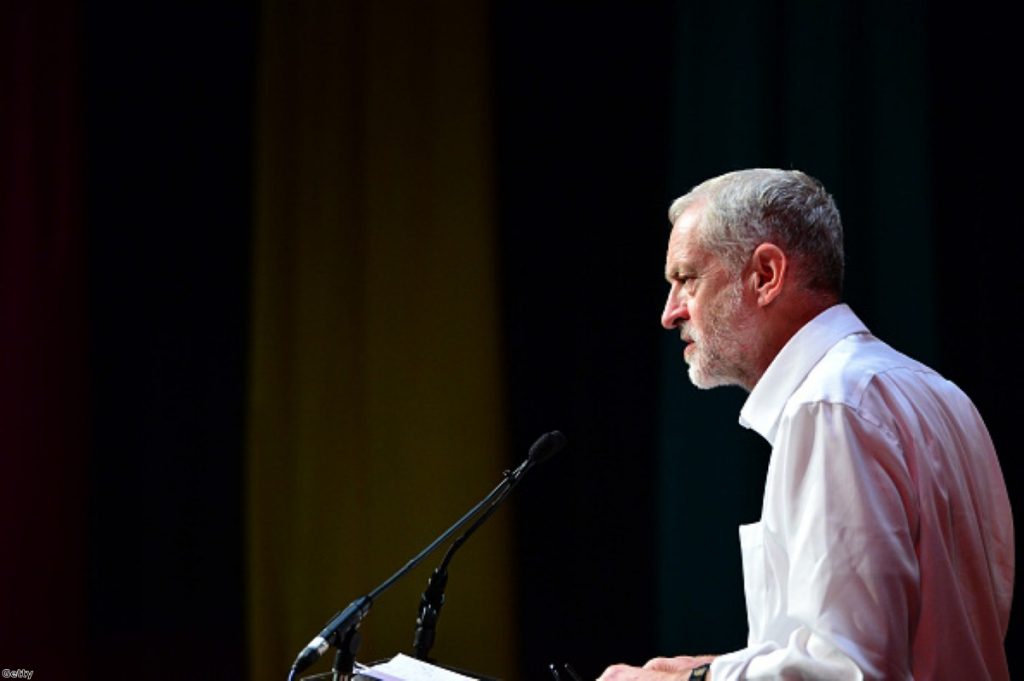

Comment: Forget economics. It’s Corbyn’s foreign policy which is really dangerous

By Ben Myring

No matter what his tabloid critics say, Jeremy Corbyn's economic policies are actually only moderately left-wing. Not so long ago they would have been regarded as centrist. But when it comes to foreign policy, Corbyn is genuinely radical.

This isn't about Trident. Retiring the obsolete deterrent, far from being an act of national suicide, would be a moderate de-escalation in line with our treaty commitments.

It's Corbyn's self-harming pacifism which is really troubling.

His plan to abandon Nato, a key part of the global security architecture, would be extraordinarily dangerous. It amounts to head-in-the-sand isolationism. Some threats to the UK, indeed to Western civilisation, require collective military action and an agreed security framework in which to enact it. Dismantling that framework would put us all at risk.

A related example can be seen in Corbyn's resistance to Britain's role in combating Isis.

It's true that Corbyn has a long and honourable record in opposing Western intervention in the Middle East and standing up for oppressed peoples in the region. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the Iraq war and subsequent botched occupation, Corbyn correctly states that Isis' rise was at least partly influenced by that intervention.

However, Isis was allowed to consolidate and flourish not in Iraq, but in the ruins of Syria, where the West's failure to support those moderate rebels who initially rose against Assad created the chaotic conditions in which Isis was able to emerge. Corbyn was one of many Labour MPs who voted against that timely intervention, creating the breeding ground in which more radical Islamist groups subsequently flourished.

Corbyn at least tries to take the historical long-view on the Middle East. His website sensibly states that:

"We need an understanding of our past and our role in the making of the conflicts today, whether it be the Sykes-Picot Agreement or our interventions in the Middle East post 9/11."

The post-WW1 Sykes-Picot agreement, in which France and Britain drew arbitrary lines in the sand to create the modern states of the Middle East, is certainly a root cause of the violence we see today. The borders cut across ethnic lines, dooming the emergent states to instability. If we allow Isis one legacy, it should be the acceptance that those imposed boundaries are now finished. They have effectively demolished the border between Iraq and Syria, and this is a significant part of their appeal to the disenfranchised Sunni Arab majority on either side of that line.

A sensible British strategy would include some recognition of this change – not least in favour of the Kurds, a broadly secular and democratic people who have long suffered from division and oppression by their neighbours as a result of Sykes-Picot. Corbyn, like many on the left, has often spoken out on behalf of the Kurds. Yet his opposition to the current coalition bombing campaign is utterly at odds with that supposed solidarity.

In June 2014, Isis crossed from Syria to Iraq and captured the major city of Mosul before launching a blitzkrieg in the direction of Baghdad. Their advance, in the face of the collapse of the Iraqi army, was slowed only by coalition airstrikes. Since then the Kurds in Syria and Iraq have faced Isis along a frontline stretching for hundreds of miles. The vigorous Kurdish peshmerga of Iraq, and the militantly secular and feminist brigades of the mainly-Kurdish YPG in Syria, have been the only successful ground forces against Isis. But their resistance would have been futile without coalition planes protecting them from above.

Corbyn has had the temerity to attend rallies in solidarity with the Kurdish-majority city of Kobane in northern Syria, from where images of female Kurdish fighters resisting the Isis siege with rusty Kalashnikovs and home-made tanks caught the attention of the world. Yet Kobane's successful defence – as the Kurds openly admit – was ultimately dependent on US air-strikes. So too in Iraq, where Isis reached the gates of the Iraqi Kurd's capital of Erbil before being repelled by coalition bombardment.

Earlier this year, Corbyn said:

"Two years ago I voted against bombing Syria when the enemy was the Assad government. I oppose bombing Syria when Isil is the target for the very same reason – it will be the innocent Syrians who will suffer – exacerbating the refugee crisis. "

Really? Refugees International estimates that Iraqi Kurdistan has accepted 850,000 refugees fleeing Isis since the crisis began, in addition to roughly 250,000 from Syria. Where exactly would these refugees go if Isis was allowed to overrun the Kurdish-defended areas? And in that event, how many of Iraqi Kurdistan's eight million people would themselves be compelled to flee across the border to Turkey, Iran or elsewhere?

If Jeremy Corbyn had his way, the crisis in Syria and Iraq would be far worse than it is today. Erbil, the shining capital of the only successful democratic region in Iraq, would have fallen to the barbarians. Women and children would have been sold into slavery, facing a life of systematic rape and hard labour. The men would have been buried in shallow graves. Kobane, and the other towns of Syrian and Iraqi Kurdistan, would have been purged of anyone refusing to accept Isis' hateful creed.

The Kurds, for all their imperfections, are a humanist miracle. Despite the geographically and politically harsh landscape in which they live, surrounded and occupied by seriously unfriendly neighbours, the lands under their control remain broadly secular and democratic. Their political parties embrace (albeit with a flawed grasp) universal human rights and they dote upon the West. They represent a beacon of hope for the entire Middle East.

Rather than turning up at public meetings to blithely recite the history of the Western betrayals of the Kurdish cause, Corbyn should look hard at his own position. He would see that, if enacted, his own policy would be the greatest betrayal of all.

Ben Myring is a policy officer with a specialist interest in Kurdish history and politics.

The opinions in Politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.