In 2011, one year after winning office, David Cameron doubled down on his pledge to cut migration numbers to the tens of thousands: “Our borders will be under control and immigration will be at levels our country can manage. No ifs. No buts”.

It was classic Cameron speak: the firm commitment to an intractable problem, a blunt sop to the Conservative right. If there was a limit to what Cameron would do to pacify his party on immigration, he had not reached it by the time of his resignation in 2016.

But the ultimatum was accompanied with a deep sense of foreboding about the political forces he was unleashing. Since 2011, it’s a pitch that has loomed large over the Conservatives as the migration target receded further and further into the distance. It was the perfect backdrop to the Brexit campaign, as the moral panic Cameron stoked and failed to harness flowed into other channels with dire portent.

So when it came time for Rishi Sunak’s grilling on ITV’s This Morning on Thursday, his defensiveness on the newly released migration figures was entirely predictable. Denying migration was out of control, the prime minister nonetheless insisted: “the numbers are just too high, it’s as simple as that”. The new record-high figure of 606,000 is over six times Cameron’s old target.

It’s also three years since the UK formally left the European Union and cut off free movement. If take back control meant anything at all in the 2016 referendum campaign, it meant get migration down. So after rumours of a post-Brexit “Swiss-style deal”, the “secret” cross-party summit on Brexit attended by Michael Gove and the U-turn on scrapping 4,000 EU laws by the end of the year, might this be interpreted as Sunak’s latest Brexit betrayal?

One problem for the PM is that Conservative MPs are beginning to doubt the government’s very commitment to cracking down on immigration. The party’s cynicism comes despite the prime minister’s announcement this week of a new tougher stance on foreign student visas.

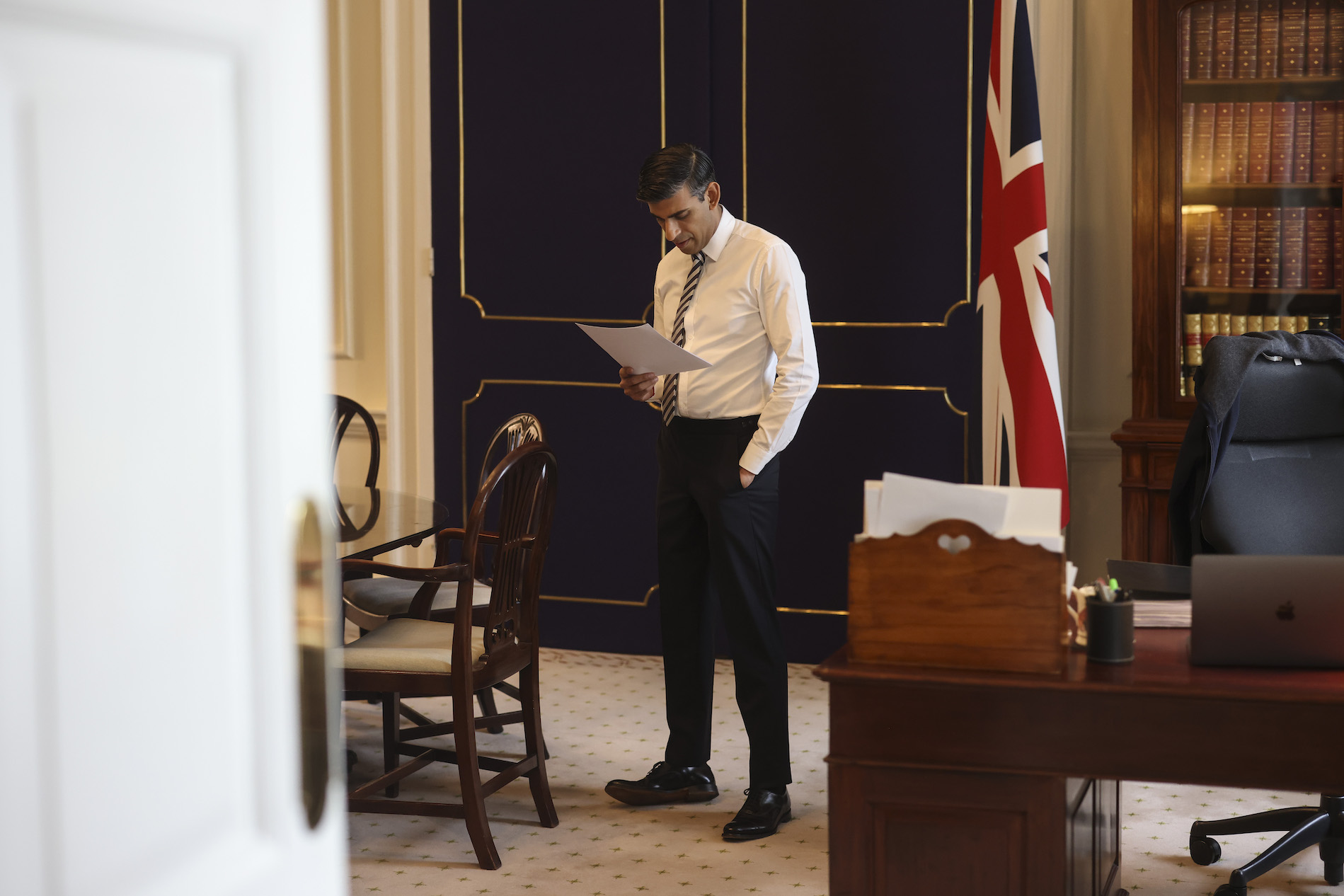

Sunak picks his way through the migration minefield

Every part of government has an interest in migration — but the two departments for which the stakes are highest on border control are the Treasury and the home office. Of course, the freelancing home secretary has made her position on immigration clear; she told last week’s National Conservatism conference: “It’s not xenophobic to say that mass and rapid migration is unsustainable in terms of housing, services and community relation”. She argued there is no good reason to bring in overseas workers to compensate for shortages in the haulage, butchering or farming industries.

Crucially, Braverman’s position seems at odds with that of the chancellor, who views immigration, unsurprisingly, through the prism of economic growth. The holder of the purse strings is always the most powerful lobbyist for keeping migration high. Hunt, alongside the education secretary, Gillian Keegan, have hence been keen to stress the economic benefits of issuing visas for workers in key sectors and students.

In short: Hunt is desperate for economic results, but Suella Braverman is desperate for immigration numbers to fall drastically. And when it comes to trade-offs which impinge on economic performance, some MPs think that Rishi Sunak, a former chancellor, may just prefer Hunt’s positioning to his home secretary’s.

Certainly, “cutting legal immigration” does not feature in the PM’s five pre-election pledges, but “grow the economy” does: it’s second — sat either side of two more economic commitments on inflation and debt. (There is also no disguising that, post-Brexit, the government has intentionally brought people in to fill gaps in sectors such as the NHS and social care. Sunak’s third pledge on “cutting NHS waiting lists” is not easily divorced from the immigration issue either).

But Braverman’s ideological allies made their voices heard in the commons on Thursday: “Some people in the Treasury seem to think a good way to grow the economy is to fill the country up with more and more people, but this is bad for productivity and bad for British workers who are being undercut by mass migration from all over the world”, said veteran MP Sir Edward Leigh.

Braverman’s closest ally Sir John Hayes, founder and leader of the right-wing Common Sense Group (CSG) of Conservative MPs, later insisted via The Independent that the PM must back changes to the visa system “quickly”.

And alongside Hayes’ socially Conservative CSG, there’s the “New Conservatives” group, formed as of last Sunday. This latest entrant to the busy Conservative caucus scene boasts the support of party deputy chairman Lee Anderson, Jonathan Gullis and Danny Kruger. According to The Sunday Times, one of the group’s key priorities is pressuring the government to bring down legal migration to avoid breaking the party’s 2019 manifesto pledge.

Given the nature of the Conservative coalition which leans heavily toward Brexit, Sunak will be aware of the political risks involved in maintaining a liberalised immigration system. Equally, the economic risk involved in tightening Britain’s immigration controls will loom large in a period of economic contraction. Such is the nature of the PM’s cross-departmental double-bind.

Then there are the parties looking to profit from the Conservative’s immigration tumult. In the hard right corner, you have Reform UK, the restyled Brexit Party led by Richard Tice, which sees itself as the natural receptacle for those disenchanted by the ruling migration regime. Their simplistic populist narrative is forged around “betrayal” and committed Brexiteer Rishi Sunak’s lack of Brexit commitment. Reform lost 474 out of the 480 seats it contested in this month’s local elections.

But conventional wisdom on the politics of migration, which suggests sceptical voters are necessarily siphoned off into a Faragist, right-of-Conservative outfit, is fast evolving.

This is not the 2010s when David Cameron so-profited from the immigration issue or 2014 when UKIP ran riot at the European elections. And, crucially, Keir Starmer is no Ed Miliband or Gordon Brown, the latter of whom infamously referred to one Labour voter as a “bigoted woman” when she raised concerns that “there’s too many people now”.

Speaking at the Confederation of British Industry’s (CBI) annual conference in November, Starmer insisted that a Labour government would wean Britain off its “immigration dependency”. Updating his approach at PMQs on Wednesday, the Labour leader lamented the “quarter of a million work visas issued last year”.

Moreover, Stephen Kinnock, Labour’s steely shadow immigration minister, has pointedly criticised the government for some of its recent liberalisation measures. His “Blue Labour”-like pitch, stressing the importance of migration controls, has raised the electoral stakes for the Conservatives greatly. Kinnock this week backed the government’s tougher stance on foreign student visas.

Significantly, Starmer and Kinnock are not merely falling in behind the government’s immigration policy — they are charging ahead. Labour is committed to keeping the existing points-based system and adding a sectoral-based approach through the establishment of union, employer and government agreements. This would require employers to sign up to a Good Work Charter, with the aim, in part, of preventing wage undercutting from migration.

It has been a long march for Sir Keir from his defence of the principle of free movement in the 2020 leadership election to, in 2022, pronouncing on Britain’s “immigration dependency”. And it has not gone unnoticed among the electorate: polls show Labour is now more trusted on immigration than the Conservatives. Of course, Sir Keir may well encounter the labour mobility-migration control trade-off down the line — especially as the party hones its pitch to big business — but right now Labour is preparing for a significant electoral dividend on the issue.

So with rising cabinet tensions and Labour increasingly strident on migration, the prime minister’s migration showdown looks set to be very cruel indeed. He could blame David Cameron for his woes, but at the next election, voters — especially those in the Red Wall — will direct their anger at him.