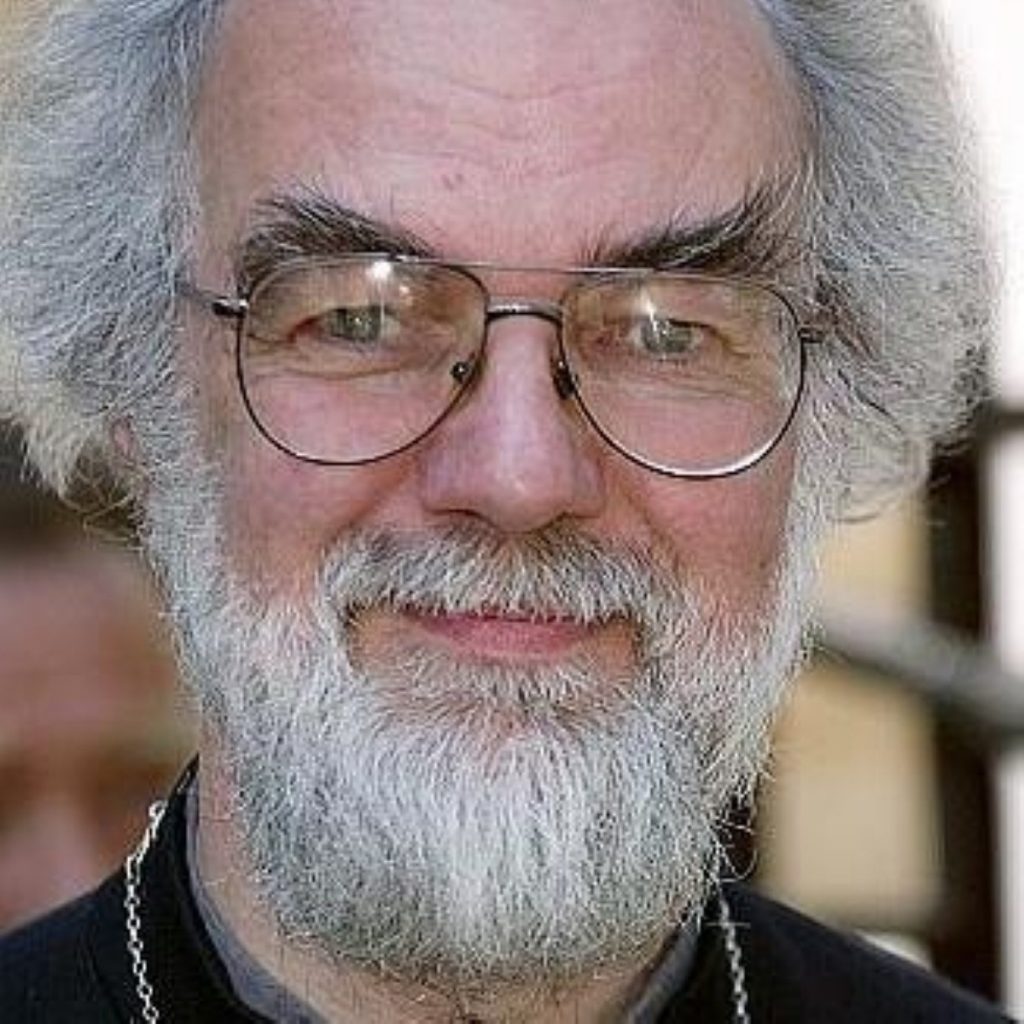

Analysis: The Archbishop shows Labour how it’s done

Rowan Williams hits a nerve by highlighting the discrepancy between the coalition's radicalism and its mandate.

By Ian DuntFollow @IanDunt

The genius of the Archbishop's attack on the coalition is that it is immune to the obvious riposte. Rowan Williams wrote in the New Statesman: "With remarkable speed, we are being committed to radical, long-term policies for which no-one voted. At the very least, there is an understandable anxiety about what democracy means in such a context."

The obvious riposte came from Liam Fox, defence secretary, and one of the few Cabinet members who wasn't implicitly tarred by the piece. "The government has legitimacy because it has a majority in the House of Commons," he said.

Fox's response is technically correct but politically flawed. Plainly, multiple parties are entitled to form a coalition government where they have a majority of seats in the Commons. But what follows from that decision, specifically in dominant policy areas, has a bearing on the democratic legitimacy of the government.

Take deficit reduction. During the 2010 election Vince Cable accepted the broad thrust of Alistair Darling's plan. The Tories committed themselves to a much deeper, quicker package of reduction and failed to win the election, despite the considerable unpopularity of the government in Downing Street. The subsequent Lib Dem decision to offer economic policy support to the Tories in exchange for concessions in other key areas does not have democratic legitimacy. In fact, as the dominant issue in the 2010 election, it goes specifically against the will of the British people, as expressed on May 6th.

The same could not be said for civil liberties, for instance. Very few people vote on this issue, but the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats held broadly similar views on the matter. They expressed those views before the election and proceeded to implement them afterwards.

Democratic legitimacy does not extend just to which policies are selected, however, but also to the extent to which a policy agenda is implemented. After one year of the coalition, Britain is witnessing one of the most dramatic periods of change in its recent history. From free schools to NHS reforms, welfare to criminal justice, the extent of the coalition's radicalism is startling.

The genius of the Archbishop's argument is that it taps into that discrepancy between the extent of change and the extent of the mandate. The one conclusion analysts could draw from the 2010 election result was that the public didn't trust anyone to run the country. It's therefore particularly galling for the coalition to implement such significant changes.

The government would reply that it has little choice. No-one will vote for a government that considers itself a caretaker for a future party's mandate. George W Bush made a similar calculation after the debacle of the 2001 election, which he plainly lost. He could have continued in an apologetic way, accepting his lack of legitimacy, or put it all behind him and govern with confidence. He chose the latter and so has the coalition.

That might make sense from the government's perspective, but it will do little to comfort those who, like Dr Williams, feel immensely uncomfortable with the chasm between mandate and implementation.

By combining its opposition to specific policy proposals with a view that alludes to a democratic deficit, Labour can tap into a potentially devastating emotional sentiment in the country. It is volatile and not, strictly speaking, constitutionally sound, but it resonates with an intuitive political sentiment which could pay significant dividends.