By Mark Harrison

This feature contains spoilers for House Of Cards seasons one to five.

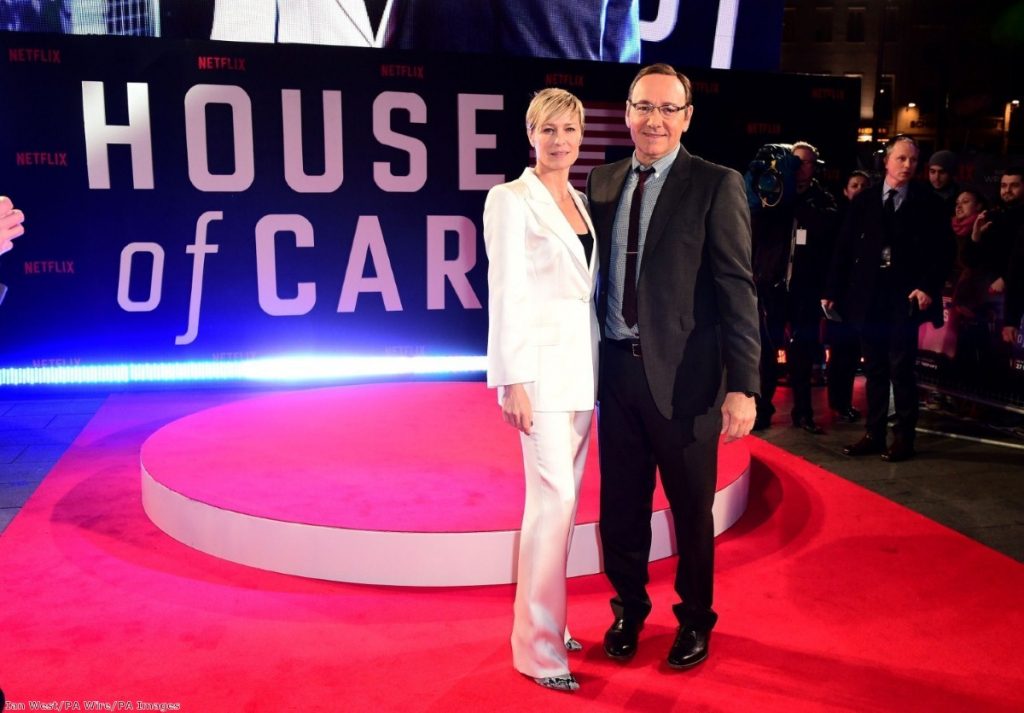

Netflix's House Of Cards has always been audacious. When it premiered as the streaming giant's first original scripted series, President Barack Obama had just been inaugurated for his second term of office and the tale of Kevin Spacey's Frank Underwood tirelessly conniving his way to greater power served as grisly, sometimes horrific, escapism from the relative calm of real life. Just imagine wanting to escape from that nowadays.

Political aide-turned-playwright Beau Willimon adapted the parliamentary politics of Michael Dobbs' novels, and the subsequent BBC adaptations starring Ian Richardson, into the US system with effortless grace. We meet Underwood as a House majority whip, expecting to be appointed secretary of state by incumbent president Garrett Walker (Michel Gill) for his efforts in the recent election. But he's passed over for the job, starting him on a bloody minded pursuit of power that sees him working out of the Oval Office by the end of season two.

Since then, its ability to wrong-foot the audience and create 'watercooler moments', even in the midst of seasons that are released all at once and intended to be consumed in the same way, has made it a huge success. There's always some trending talking point from each season in the week after it's released, from the murder of reporter Zoe Barnes (Kate Mara) at the start of season two, to the mid-season four assassination attempt on Frank, the latter of which may be the pinnacle of the series' twists.

Recently, as American current affairs have become increasingly unpredictable, the story had to become more audacious in order to remain topical. But this week, the daily horror show of the real life news cycle finally seemed to overtake the series. Revelations about Spacey's alleged sexual misconduct, and the controversy surrounding his subsequent apology, have prompted Netflix to announce that the upcoming sixth season, currently filming in Maryland, will be its last. Last night, the company halted production altogether, raising questions about whether the current season will even be released.

It's an extremely bittersweet turn of events for fans of the series. It has outrun the British version, which ran for 12 episodes between 1990 and 1995, by tens of episodes. But of course, a major part of its success lay in widening the focus to a political power couple.

Frank's wife, Claire Underwood (marvellously played by Robin Wright), has been ever present since the beginning, but took more and more prominence with each season. Their mutual flaw, their lust for power only for the sake of power, drives the chaos. They demonstrate this in their apparent passion for vote-getters like employment programmes and clean water initiatives, which come up repeatedly but are then are callously and deliberately waylaid.

As deeply plotted as it is, the writers couldn't have planned for the shock result of last year's presidential election. But their choices left them better placed than other POTUS-focused scripted shows, such as Designated Survivor, Homeland and Scandal, to remain relevant in the immediate aftermath.

The latest season addressed the oft-tweeted joke that the Underwoods couldn't possibly be worse than the unreal reality of President Donald Trump head on. And sure enough, there are references to an illegal travel ban designed to outrage and distract people from a constitutional crisis, an ongoing conflict with Isis analogue ICO and, most pertinently, the Underwoods waging domestic cyber warfare by gathering voter data in the general election and using it to suppress their opponent's supporters.

Crucially, this is where the show starts to unsettle even its most hardened viewers again. It's famous for Spacey's adaptation of Richardson's soliloquies, occasionally turning to break the fourth wall for long, personal speeches. A spectacular example comes during Frank's inauguration, when he accuses the voters (or the viewers) of being complicit. We know he's bad and we keep watching, and so we get the leaders we deserve. Still more discomfiting, Claire starts to talk to us as well, and we have to wonder how long she knew we were there.

But the show still pushes the envelope a little further than just adapting topical malfeasance for the Underwoods. By the season's end, Frank has managed to appoint his wife as vice-president, hospitalise his secretary of state by pushing her down a flight of stairs, and arrange a fatal traffic collision for his campaign manager. Most spectacularly of all, he resigns in order to make way for Claire as America's first female president, ever so slightly over-confident that she'll pardon him in the face of increasing evidence of his crimes.

With so much happening, it doesn't feel like they could have dragged it out to the next logical end point of eight years (the constitutional maximum length of time that a president can serve) but Netflix is in an unenviable position, given the extent of the social media outrage over the Spacey story.

House Of Cards is the house that built Netflix – it's more scabrous and deviously plotted than The West Wing, the beloved gold standard of this particular sub-genre, but just as watchable. Truth has become stranger than fiction and the long-form portrait of its two central characters' warped psychology and audacious power manoeuvres has done well to outpace the unpredictable news cycle. It is cruelly ironic that, in the end, that same news cycle finally toppled it.

Mark Harrison is a writer with an interest in the crossover between politics and entertainment. He writes for Den Of Geek and VODzilla.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.