The government’s decision to nationalise Greater Anglia, the best-performing operator in the country, shows mistaken priorities. Instead of focusing on failing services, ministers are risking disruption to a railway that has been transformed and is paying money back to the exchequer. Meanwhile, passengers suffering the worst services are told to wait their turn.

Greater Anglia has led the national punctuality league every month for two years, with the industry’s key on-time metric running at about 94% of services (against an industry average of c.87%). Its private owner has delivered a complete replacement of the fleet: new, energy-efficient trains with level boarding, Wi-Fi, power points and greater capacity across the network, alongside station upgrades and targeted journey-time reductions (for example, 6–7 minutes off the Norwich–London timetable). It amounts to over £1.5 billion of private investment benefiting passengers and the region. And unlike most of the network, Greater Anglia has been sending a premium back to the Treasury, well over £100 million in 2024.

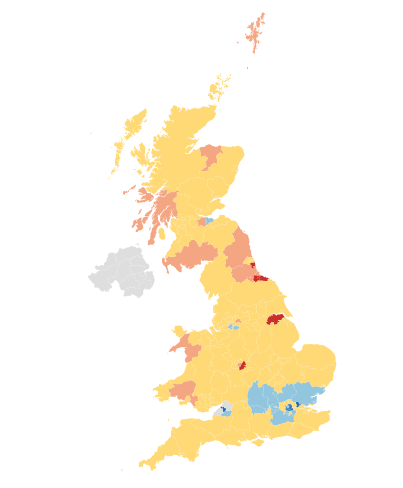

So why start here? If nationalisation is really about improving services, the obvious place to begin is with poor performers. Take CrossCountry. Last year, the former transport secretary wrote to the operator raising “serious concerns” about cancellations, approving (reluctantly) a temporary timetable reduction and placing the company on a remedial plan, while making clear further action could follow if performance did not improve. Ministers have acknowledged they can terminate underperforming contracts early where the terms are breached, rather than waiting for expiry. But they haven’t. Instead of tackling a chronic underperformer, the government’s programme brings stable, high-performing services into public ownership first. That is the wrong way round.

Ministers also argue that nationalisation is about affordability. The public agrees affordability matters, but they are sceptical that a state takeover will deliver it. A recent YouGov survey found that while two-thirds back nationalisation in principle, support collapses to just 6% if fares keep rising. Unless and until ministers can show how fares will be reduced without starving the railway of investment, the promise of cheaper tickets is not a plan, it’s a hostage to fortune.

There is a cautionary tale north of the border. ScotRail was taken into public ownership in 2022 amid great fanfare. Since then, the numbers have gone the wrong way – higher subsidy and costs, more staff, performance pressure and tens of thousands of cancellations. In fact, it has been reported that the cost of the railway services is nearly £600 million more in the first two years of nationalisation than when it was operating in private hands. If Greater Anglia starts to go in a similar direction, Labour will find itself in a high-risk situation where the entire policy approach is undermined.

None of this is to deny the merits of rail reform. Bringing track and train closer together through Great British Railways is overdue and a Conservative idea originally born out of the Williams-Shapps Plan for Rail. But doing piecemeal nationalisation before the GBR model is developed, before a clear performance and incentives framework is agreed, and while the government is still marshalling the resources for a vast organisational change, is risky and ideological rather than practical. It is a policy that is there purely from weakness to please Labour’s trade union paymasters. It absorbs management bandwidth on lines that are working, precisely when the state should be laser-focused on turning around those that aren’t.

You don’t need nationalisation to bring track and train together. But if the government is set on the political experiment, it should at least do it in a rational way that minimises damage. A better approach is available. First, prioritise taking on failing operators, starting with the worst performers and setting out transparent, passenger-facing recovery plans. Second, let proven, high-performing concessions run until GBR is ready. That keeps standards high, protects the taxpayer, and avoids a destabilising demobilisation of experienced teams. Third, be honest on the cost of nationalisation: if ministers do not intend to reduce fares now or in the future, they should articulate that clearly to passengers, and they should also come clean to the taxpayers. They will have to spend a lot more on subsidising rail to make up for lost private sector investment. From now on, new trains for Greater Anglia won’t be funded by private investment – it will be taxpayers.

The Greater Anglia experience shows what focused management, private capital and clear targets can achieve. It has delivered new trains, faster journeys, better accessibility and the best punctuality in Britain, while paying a premium back to taxpayers. Nationalising it does nothing to help passengers enduring poor service elsewhere. If the government is serious about improvement rather than satisfying rail union demands, it should start where the problems are, not where the headlines are.

After all, think of a nationalised business or organisation that has a reputation for good management. Me neither.