Oldham East: What the Muslim community is really thinking

A decade after the Oldham race riots, Oldham’s Muslim community continues to feel frustrated and victimised. Who is letting who down?

It’s a cold, dark night in Glodwick, on the eastern side of Oldham. This, I’m told, was the part of the town at the heart of the 2001 race riots. Locals from nearby affluent Saddleworth have told me it remains one of the most deprived parts of the country. I’m sat parked in a car in the rain and the pitch black, 15 minutes early, staring at a tired-looking building on a quiet side street. Eventually I get out and walk over to the entrance. On approaching the door, I’m greeted with a smile – but also told to wait outside. “They’re praying now,” the woman explains. Rather than hang around getting wet, I retreat to the car.

Eventually two groups turn up. Leading the first is a large man, Kashif Ali, the Conservative candidate for the Oldham East and Saddleworth by-election. Last May he managed to turn the seat into a three-way marginal, stealing votes from both Labour and the Lib Dems to come a close third. This time round, he’s hoping to do even better.

Shortly afterwards a Jaguar sweeps into the car park opposite. Out gets Elwyn Watkins, the Liberal Democrat who brought about the election court which stripped Labour’s Phil Woolas of his seat – and brought about the by-election taking place later this week. I slip out of the car and tag along with the Lib Dems. We take off our shoes, make jokes about holes in our socks, and step inside.

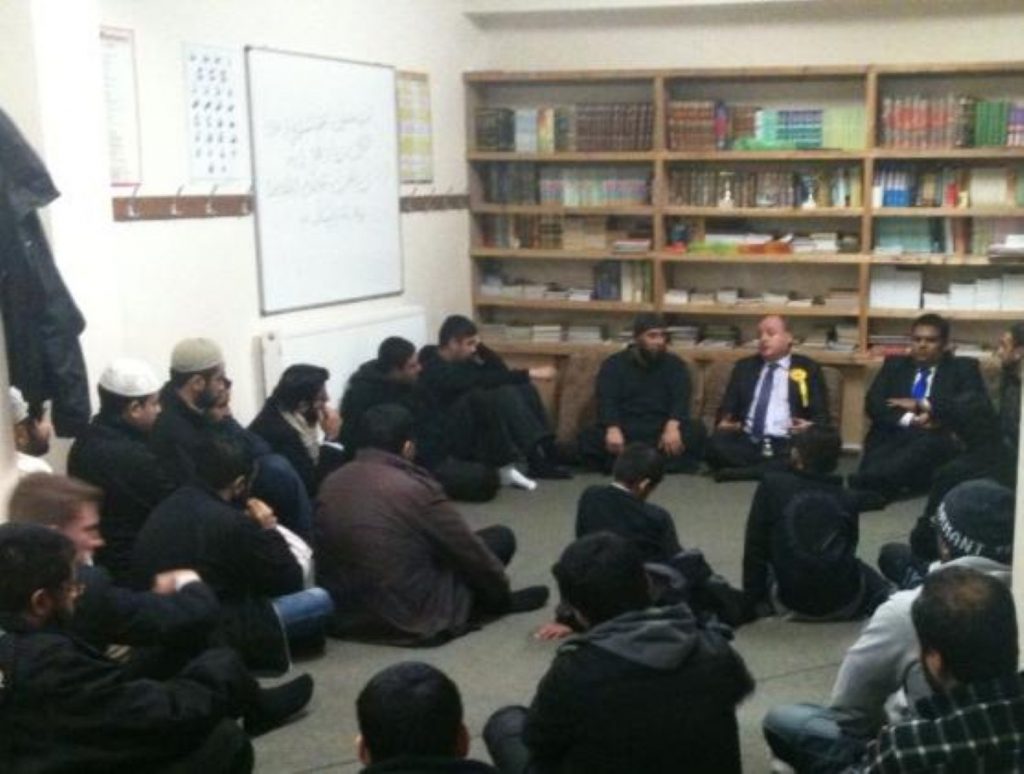

There’s about 50 locals inside. The vast majority of them are male. This is an educational centre; I notice Arabic scrawled on a whiteboard and a garishly-coloured ‘Islamic manners’ poster on the walls. After some milling around and friendly shaking of hands we’re called to order, sitting down cross-legged around Watkins and Ali. The politicians get faded sofa cushions to lean on. The more astute stick to the walls. I’m sat in the middle, my left leg slowly going numb.

The next 90 minutes is what Watkins afterwards calls a “fluid discussion”: it’s mediated, yes, but without the stiff-collar primness of church meetings of this kind up and down the country. Everyone has a view and wants it to be heard. At least one man appeared to be making his feelings heard by erupting into loud fits of snoring. Always, those in charge were able to quell any shouting with a wave of the hand. This was just as well, for feelings were running high.

The big grievance of this community can be summed up in one unpleasant word: Islamophobia. It was raised again and again, the same problem at the heart of most of the controversial issues raised. They demanded condemnations of Oldham MEP Chris Davies, a Lib Dem, for comments about the hijab. They wanted to know what steps could be taken to combat the English Defence League. Worst of all, they were outraged by former home secretary Jack Straw’s comments this weekend that the Pakistani community needed to prevent its youths from “preying” on white girls.

“When a Muslim does something, it automatically becomes a reflection on the community,” one said. He seemed outraged. “As a member of the community, I’m certainly not responsible!”

Another was even more miserable: “Islamophobia is one of the biggest challenges facing Muslims today. A small minority of people does an action, and it’s condemned by the right-wing press, the right-wing politicians…” The media have a real responsibility for the problem, it seems. Why report the headline ‘Muslim cab driver robs passenger’ when ‘Cab driver robs passenger’ would do?

Politicians don’t experience this sense of alienation, perhaps because they’re much closer to power and influence. Even Ali, a discrimination lawyer, was of the community but not of them at the same time. “Things are pretty cosy,” he said, describing his circumstances, confronting the issue head on.

Much of the time both Watkins and Ali were on the defensive, especially when repeatedly asked to “condemn” this or that. When Palestine was raised, for example, the demands were at their most intense. “I said I would not sell arms to any country that sells civilians,” Watkins finished at the end of a long answer about his views on the Middle East. “So you’re condemning Israel?” the questioner asked. “I would condemn the actions of the Israeli government, not Israel,” Watkins replied.

It was, put simply, easier for Ali to deal with this audience. “It’s our furthermost issue!” someone shouted out, full of exasperation, as Ali too refused to condemn the state of Israel outright. Forget jobs, forget the economy: would Ali fight for Palestine if he was elected? “I would!” he insisted, finally abandoning his political caveats. “I don’t think Elwyn wouldn’t, but there you go.”

That was strange. Had the Tory just stood up for his Lib Dem candidate? The headlines have been full of stories about the impetus of Ali’s campaign being downplayed by the Tory leadership, eager to avoid an embarrassing Lib Dem drubbing by Labour. In fact it just felt like a generous remark. In any case, Watkins was running into trouble of his own.

“If you’re going to challenge the prejudices, why not do something positive about it?” he suggested, after yet another exchange over Islamophobia. Seeing a couple of hundred members of the Asian community turn up to a remembrance service would send a powerful signal. “It’s a Christian remembrance!” they replied scornfully. “No it’s not,” Watkins insisted, a trace of irritation beginning to show. “People of all faiths come there.”

He tried another tack. “It would be so nice to see [someone write] a letter” from the Muslim community, published in the local newspaper, as an alternative. “People do! But it never gets noticed. We face these challenges day in, day out.”

After the event had finally ended I discovered a surprising mix of opinion about the by-election. One man wanted to see Phil Woolas return. “I’m starting a petition,” he said, a little optimistically. His friends waved their hands dismissively. One said he would refuse to vote Conservative, regardless of Ali’s ethnicity. Another said he was a friend of Kashif and would be backing him – although he liked the Lib Dem, Watkins, too.

The question of whether to choose a candidate had been briefly addressed, in the context of the wider make-up of the Commons. Ali got his message across: “The more representative the parliament, the better the decision-making.” Watkins was forced to be more circumspect. He was referring to Labour voters not bothering to make an informed decision, but the meaning was clear. “I would say we have the sheep factor in many of our communities.” This struck me as pretty outrageous, but no one seemed to react especially angrily. Afterwards, Watkins wanted to know whether the fact that Labour’s Debbie Abrahams had not bothered to turn up would “get out into the community”. He was cheerfully assured it would.

Ali seemed upbeat afterwards, too. He told me this was the first Muslim hustings organised in the by-election and was delighted it had gone so well. Watkins, he added, had skipped a discussion on Kashmiri issues three weeks earlier, without even giving a reason. With a by-election so close, he was clearly in fighting spirit. When the Muslim community votes on Thursday, many of them will be tempted to back him over their traditional party of choice, Labour – whose candidate Abrahams had better things to do.

Back out into the rain, then, and a cold wait for a taxi. Funny, I thought: as I watched the meeting’s attendees disperse for the evening from the other side of the road, the building looked less dank, less unpleasant, less grim than it had two hours before.