The British public deserves a better election than this

Britain almost ceased to be six months ago. Both its main political parties are now proposing spending cuts so severe they threaten to fundamentally change what we think of as the state.

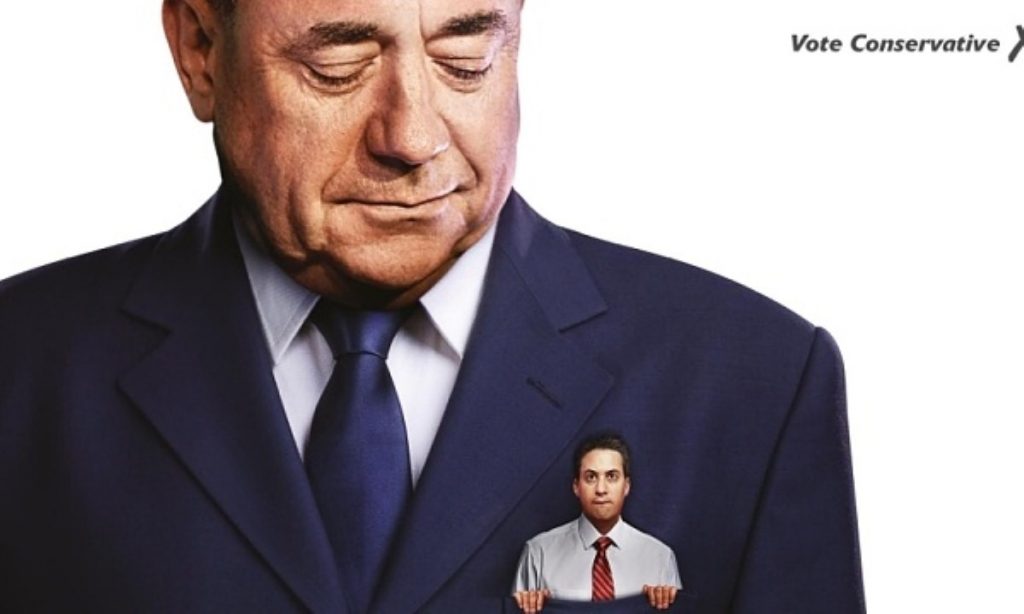

These seem big, even existential issues for a country to face. And yet the election campaign is composed of tiny, soap opera-like tittle-tattle. Yesterday's inane Tory poster, showing Ed Miliband in the pocket of Alex Salmond, typified it. Conservatives believe they've found a red line and are trying to push Miliband over it by making everything about a possible SNP pact.

Alex Salmond slams Tory election poster which shows Ed Miliband in his pocket http://t.co/dvVlPzaSV0 pic.twitter.com/V2kjwPxWvV

— The Daily Record (@Daily_Record) March 10, 2015

Labour believes it has found a red line over David Cameron's refusal to do the TV debates and has spent the last week publicising it as much as possible. Where coverage is not about these twin issues, it is designed to seduce the core vote: on economic issues for the Tories, on the NHS for Labour.

This is a big, historic moment in British history, but future students will not be much bothered by the reaction of MPs or political parties. Their response to the constitutional, financial and political crises of our time is just an immature murmur amid events they do not seem to fully comprehend. They are like a child blithely watching SpongeBob SquarePants in the corner of the room while his parents organise their divorce on the kitchen table.

No British patriot could have gone through the Scottish referendum and its aftermaths without recognising the need for real, substantial reform of the country's constitutional arrangements. But the questions are even bigger than that. This was a referendum on Westminster more than it ever was on Britain. If alienation from our political system has reached the level where people are drifting away from the country itself, it demands a fundamental change in the way we do politics.

But this has proved too big an issue for our politicians to grapple with. Cameron responded the day after the vote in the most pernicious, party-political way imaginable, by trying to placate reactionary forces in his own party with a new-found focus on English-votes-for-English-laws. His only response to monumental constitutional issues is to seek for breadcrumbs of party-political advantage.

This is one of Cameron's great recurring themes as prime minister, although it is probably more the product of George Osborne than it is the man in No.10. It is evident in the great recurring lobbying scandal, where Cameron used a bill to attack Labour rather than deal with second jobs and cash for influence.

Now we see the same old behaviour from Jack Straw and Malcolm Rifkind that we saw going into the 2010 election.

Meanwhile, Osborne's economic plans, which demand massive cuts to spending, resist any tax rises, and then earmark further cuts to pay for pre-announced tax hand-outs to the middle classes, constitute the greatest economic change this country will have seen since the early eighties. Ed Balls yesterday warned – reasonably enough – of £70 billion of cuts. But the shadow chancellor's intervention was not a real attempt to grapple with the issue. He did precisely what Cameron did with the Lobbying Act – turn a matter of real concern into a party-political battering ram. Because if Labour was prepared to behave responsibly and treat the British public with the intelligence it deserves, it would release some information about its own plans for cuts after the election. As things stand, the public are being asked to vote on an economic prospectus without being given any of the detail.

Few question the fact that cuts are unveiled after the election rather than before it. But why should they be? One would not order in a restaurant after the food has been delivered. It simply makes no sense. There is something poisonously coy about the Labour and Conservatives approach to cuts and the election. A mature democratic society would insist on the menu of cuts before we decided to accept either one of them. There would, at the very least, be media pressure for it.

These great twin issues of Scotland and public finances take place amid a background of long-running global and domestic pressures. Today, the Social Market Foundation will release a report showing the gap between the richest and poorest growing wider. Miliband has much to say about this issue but precious little to offer. He talks big, but his policy proposals are supremely cautious and borderline illiterate.

NEW: By 2012-13, average financial #wealth among the lowest #income group was 57% lower than in 2005 http://t.co/FeZRVKyBUU

— SMF (@SMFthinktank) March 10, 2015

Those on the lowest incomes have less than six days’ worth of #income in #savings http://t.co/DpzbcfISyj finds new SMF @usociety report

— SMF (@SMFthinktank) March 10, 2015

In foreign affairs, war has erupted in Europe while the rise of Isis and the continued Sunni-Shia civil war comes just as western defence budgets are slashed in the name of austerity. The Tories pride themselves as the party of defence, but they have little offer on this troubling trend, beyond spurts of internecine warfare and some chest-thumbing speeches by armchair generals on the backbenches.

The idea we would have a serious debate, let alone a serious party prospectus, on these issues is now considered naïve. Our politicians are fixated with silly, tiny games which do nothing to address the issues facing the country.

This is partly the result of how we select our politicians. A broken electoral system fixated on a tiny number of marginal seats and a party-political culture which values obedience and effective 'messaging' over independence of thought have given us a shoddy, inadequate political class.

But it is also the result of how these politicians think of us. They plainly imagine the public are idiots, because that is how they treat them. Only the most inadequate of minds would be satisfied by the answers the Tories have given us on the relationship between Scotland, England and Wales, or the ones Miliband has presented on the cost of living. And yet that is exactly what they have offered.

Perhaps the publication of the manifestos will prove a surprising moment in which the political class shows a renewed seriousness and responsibility matching the times in which it operates, but there is precious little reason to be so optimistic. When politics is so insubstantial, it is small wonder voters are throwing their lot in with the SNP, Ukip and the Greens. Our politics is already small, so you might as well vote for a small party.