What is fertility treatment?

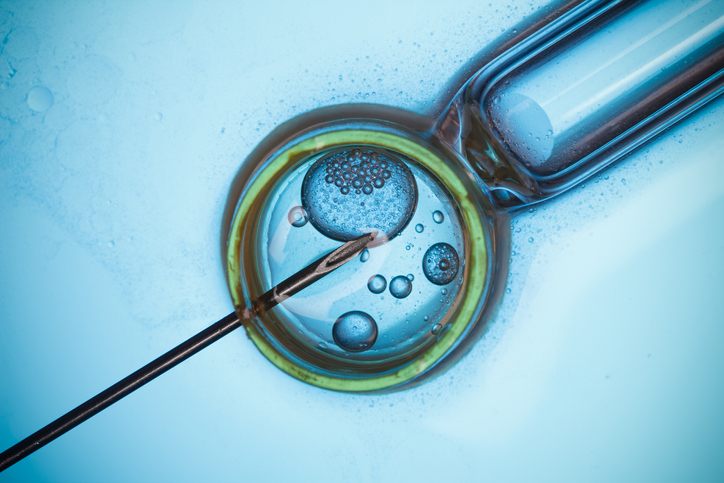

Fertility treatment is the use of medical intervention techniques to aid the natural process of conception in the face of male infertility or female infertility.

Most people seeking fertility treatment are not entirely ‘infertile’; rather one or more parts of their reproductive systems are impaired, and they therefore require medical help to conceive. This is referred to as ‘sub fertility’ as opposed to ‘infertility’.

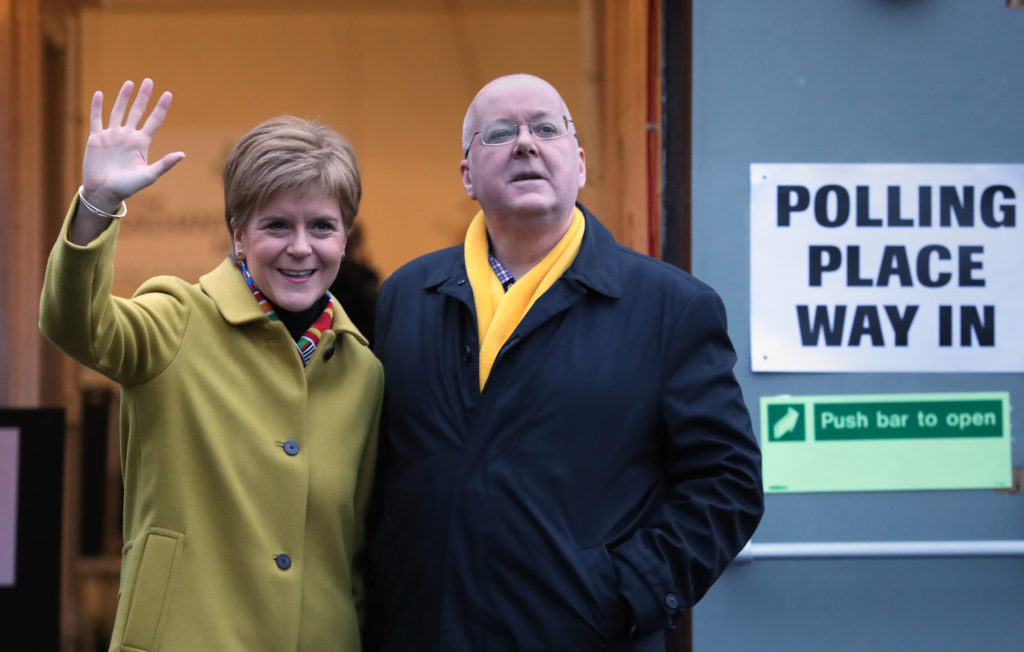

Varying access to fertility treatment has become political controversial in recent years.

For men, the most common cause of ‘sub fertility’ is due to poor sperm quality. For women the matter is often more complicated and can be caused by a number of factors.

Fertility treatment is provided in the UK by individual clinics around the country, specialising in different forms of treatment and providing a variable quality of service and price. High-tech treatments, such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and treatments using donor sperm, donor egg and embryos, are regulated in the UK by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA).

Different causes of infertility or of a fertility problem require different intervention techniques. The most frequently used treatments are: ovulation induction (hormone treatment); artificial insemination, using the partner’s sperm and intra-uterine insemination; surgery to improve a blocked or damaged fallopian tube; gamete intra fallopian transfer; IVF; intra cytoplasmic sperm injection; sperm donor insemination; and surgical sperm recovery.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends that couples who have been unsuccessful in conceiving after two years are offered three full cycles of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) for women under 40, and one cycle for women between 40 and 42.

However, these are guidelines, and a local Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) is not legally required to follow them.

Campaigns over access to fertility treatment

Given the ability for local Clinical Commissioning Groups to make decisions around access to fertility treatment, substantial differences in the funding of fertility treatments have emerged between different areas of the country.

This has led some campaigning groups such as Fertility Fairness to previously highlight how many people are denied access to fertility treatment. The group used Freedom of Information requests to discover that 60% of Clinical Commissioning Groups only offered one cycle of paid for IVF treatment under the NHS, as opposed to the NICE guidelines of three cycles. Whilst four Clinical Commissioning Groups had fully decommissioned their fertility services: Mid-Essex, North East Essex, Basildon & Brentwood and South Norfolk.

The campaign group point out how the World Health Organisation classifies infertility as a disease and, argue as with any other medical condition, it is deserving of treatment in which a patient has full access to reproductive medicine and a fertility specialist.

In 2016, Fertility Fairness found the number of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in England offering the recommended 3 IVF cycles to eligible women under 40 had halved in the previous 5 years: with just 12 per cent now follow national guidance, down from 24 per cent in 2013.

There has also been criticism of the current postcode lottery that governs access to fertility treatments. In 2016, of the 35 clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) offering three NHS-funded IVF 3 cycles, the vast majority, 28 CGGS, were in the north of England.

Those couples unable to access fertility treatment are faced with having to approach a private fertility clinic. Undergoing fertility treatment privately for many couples at a fertility centre may be prohibitively expensive.

History of fertility treatment

Early Years

Fertility treatment has been at the cutting edge of medical science throughout the 20th Century. The year 1928 saw the first sperm counts taken and the first hormonal induction of ovulation. The first children conceived through Artificial Insemination were born in 1934 in the USA.

In vitro maturation of animal oocytes was proven to be possible in 1939, but it was not until 1978 that the first ‘test tube baby’, Louise Brown, was born. The first Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis baby was born in 1990 and the first intracytoplasmic sperm injection baby was born in 1992.

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority Act – 1990

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) was set up under the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority Act to license those providing fertility treatments and conducting fertility research, including the NHS, and began work in 1991.

Clinics and researchers are obliged to adhere to the HFEA Code of Practice, and are subject to inspection. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority also provides information and guidance for prospective parents seeking to undergo fertility treatment. It is also required to ensure clinics “take account of the welfare of any child who may be born as a result of the treatment (including the need of that child for a father), and of any other child who may be affected by the birth”.

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority also has an explicit role in promoting public debate about fertility treatment and medical research.

The 1990 Act was amended in 2001 to allow the use of embryos for stem cell research and to provide for its regulation.

February 2004 saw the publication of national guidelines on fertility treatment by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), with the aim of providing consistent NHS fertility treatment across the country.

In January 2004, the Government changed the rules for egg and sperm donation, ruling that children conceived through fertility treatment would have the right to know who their biological parents were. But, egg and sperm donors would have no obligation to meet with their biological children, or provide them with financial support. The new rules came into effect in April 2005, and are not retroactive, so children conceived before this date would not be able to access details about egg and sperm donors.

The number of sperm donors has been falling for a number of years, but although this was expected to get worse once donors lost their anonymity, there is no evidence to back this up. The shortage has prompted clinics to look overseas for sperm donors. If the number of sperm and egg donors fails to keep up with demand, there is some concern that couples will travel overseas to receive treatment, where fertility treatment is sometimes not as tightly regulated as in the UK.

The 2008 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act

In 2007 the government announced plans to overhaul fertility legislation in light of the many technological developments that had arisen over the previous two decades. The subsequent Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 mainly amended the 1990 HFEA Act.

The new Act included measure to ensure that all human embryos outside the body, and all “human-admixed” embryos created from a combination of human and animal genetic material for research would be subject to regulation; to ban sex selection of offspring for non-medical reasons; and to recognise same-sex couples as legal parents of children conceived through the use of donated sperm, eggs or embryos.

Also in 2008 the Department of Health established an Expert Group on Commissioning NHS Infertility Provision with the aim of identifying barriers to the implementation of the NICE fertility guideline and helping NHS commissioners in their decision-making on infertility treatment provision. In its interim report the Group’s recommendations included the establishment of a “clinical pathway” and a “national tariff” for regulated fertility services. The final report was published in January 2010.

Fertility treatment – Past controversies

Fertility treatment is a highly controversial area of medicine: it can be medically risky for participants and is frequently very emotionally exacting; it is expensive; and the development of new techniques raises complex and controversial ethical questions. More widely, it generates debate about the international regulation of medical research and the commodification of human life itself.

Few, however, would question the right of couples to seek medical assistance if they are having difficulties conceiving, and many of the techniques described are widely accepted. Today, IVF treatment is relatively commonplace, but in 1985, a Private Member’s Bill sponsored by Enoch Powell was almost successful in outlawing all research on human embryos altogether, mirroring the current debates about stem cell research.

Controversies arising from evolving fertility treatment keep the subject near the top of the media agenda: advancing technology permits older parents to conceive, the healthy sperm of dead fathers to be used, and the precise characteristics of babies to be ‘designed’. The heart of the problem is where the line between fertility treatment, cloning and genetic engineering lies.

One scandal arose in 2003 when black twins were born to a white couple at a Leeds IVF clinic – prompting extensive judicial activity to establish their actual legal parenthood. In January 2005 a 66 year-old Romanian woman gave birth to a daughter after fertility treatment, making her the oldest mother in the world. The case provoked controversy, with some terming the woman involved as ‘selfish’.

The availability of fertility treatment on the NHS, and its alternatives, remains a matter of controversy. Access to services can be difficult to secure, and many prospective parents have to use expensive private clinics. While those on lower incomes do not have this option, the range of services available to the wealth outside the UK and its regulatory environment raises questions about the commercialisation of reproduction and the ethics and motivations of ‘rogue’ doctors.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence’s 2004 guidelines aimed to address availability problems by recommending that every couple be given access to IUI and IVF treatment. However, the Government’s response – on cost grounds – that IVF treatments be limited to one course per couple caused widespread disappointment, particularly in view of the fact that the first course was often unsuccessful and useful for diagnostic purposes only.

The role played by the HFEA in setting ethical boundaries has also caused controversy, particularly in cases involving genetic screening of embryos. When, in November 2004, the HFEA granted the first licence to a clinic to screen embryos for diseases they might develop as adults, it was accused of taking a major ethical decision behind closed doors.

The clinic involved in the controversy wanted to test embryos for the genetic mutation that causes familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP), which strikes in the early teens. It causes multiple rectal and colon cancers and most people with the condition end up having their colons removed. Although there are strong arguments for embryo selection for this disease, critics worry that if genetic selection is allowed, it will be the beginning of a slippery slope towards outright genetic engineering.

Issues of consent rose to prominence when Natalie Evans lost her court battle to be implanted with embryos created in a former relationship. Her ex-boyfriend refused to allow Ms Evans to attempt to carry their unborn child to term, despite consenting to the original fertility treatment. The case went all the way to the European Court of Human Rights, which upheld the British courts’ original decision that consent can be withdrawn up until the point the embryos are implanted. Ms Evans argued the ruling violated her right to a family life.

The debate over fertility treatment shows no signs of abating, with each new scientific advance heralding a fresh wave of controversy. Among the most controversial proposals was the creation of hybrid human-animal embryos, which scientists claimed was necessary to provide sufficient material for research.

Statistics

Difficulty conceiving or unexplained infertility is a problem that affects around one in seven couples in the UK. 84% of couples will conceive naturally within a year if they have regular unprotected sex, while 92% will conceive within two years. [Source – to NHS Choices]

For couples who have been trying to conceive for more than three years without success, the likelihood of pregnancy occurring within the next year is 25% or less. [Source – to NHS Choices]

“The average cost of one full cycle of IVF is £3,483. This is the mean average of a wide range of prices offered by service providers to CCGs – from £1,343 to £5,788” – [Source Fertility Fairness – Political Briefing, 2017]

Difficulty conceiving is a widespread problem. It is the second most common reason for women of childbearing age to visit their GP, the most common reason being pregnancy.[Source Fertility Fairness]

Quotes

“Assisted reproduction is a fast developing field whose regulation raises fresh challenges on an almost daily basis. It is a privilege to preside over that regulation. I am determined that this crucial work is continued to the highest of standards during this period of change.” – Prof Lisa Jardine on her re-appointment as chair of the HFEA.