Call to allow parental consent in embryo research

Ministers and MPs are being asked to consider lifting a ban on taking cells from dying children for medical research.

Campaigners argue there are practical difficulties to obtaining consent, potentially impeding research into fatal diseases such as Tay Sachs and Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA).

The Genetic Interest Group, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust and UCL Institute for Child Health have written to health minister Lord Darzi calling for an amendment to the human fertilisation and embryology bill which would allow parents to consent to their child’s genetic material being used in medical research.

The letter states: “The bill, as it stands, imposes a barrier to one of the most potent tools for research into the most severe childhood diseases.

“Given the existing regulatory framework that provides for proper informed consent procedures where children are concerned, there is an overwhelming moral argument for the bill to be amended so that consent is brought into line with other health and research activities.”

The Department of Health promised to “examine the issue carefully”.

A department spokesperson said: “The government believes that some very strong and persuasive arguments have been put forward for cases where, perhaps because the child is suffering from a terminal illness at a very early age, the current consent requirements in the bill are not appropriate and should be revised.”

Under the current terms of the bill, cells cannot be taken without the child’s consent. But campaigners are concerned many children die or are otherwise incapable of giving consent.

They point out in most other medical procedures, for example consenting to high-risk surgery, the burden of consent lies with the parents.

The letter argues the framework created by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority and Human Tissue Authority is sufficient to protect against misuse of children’s genetic material.

The neurological disorder Tay Sachs can be fatal by the time a child is six, while SMA can kill at 12 months. With other diseases such as Lissencephaly the child’s brain does not normally develop beyond six months, meaning the child is not capable of giving consent.

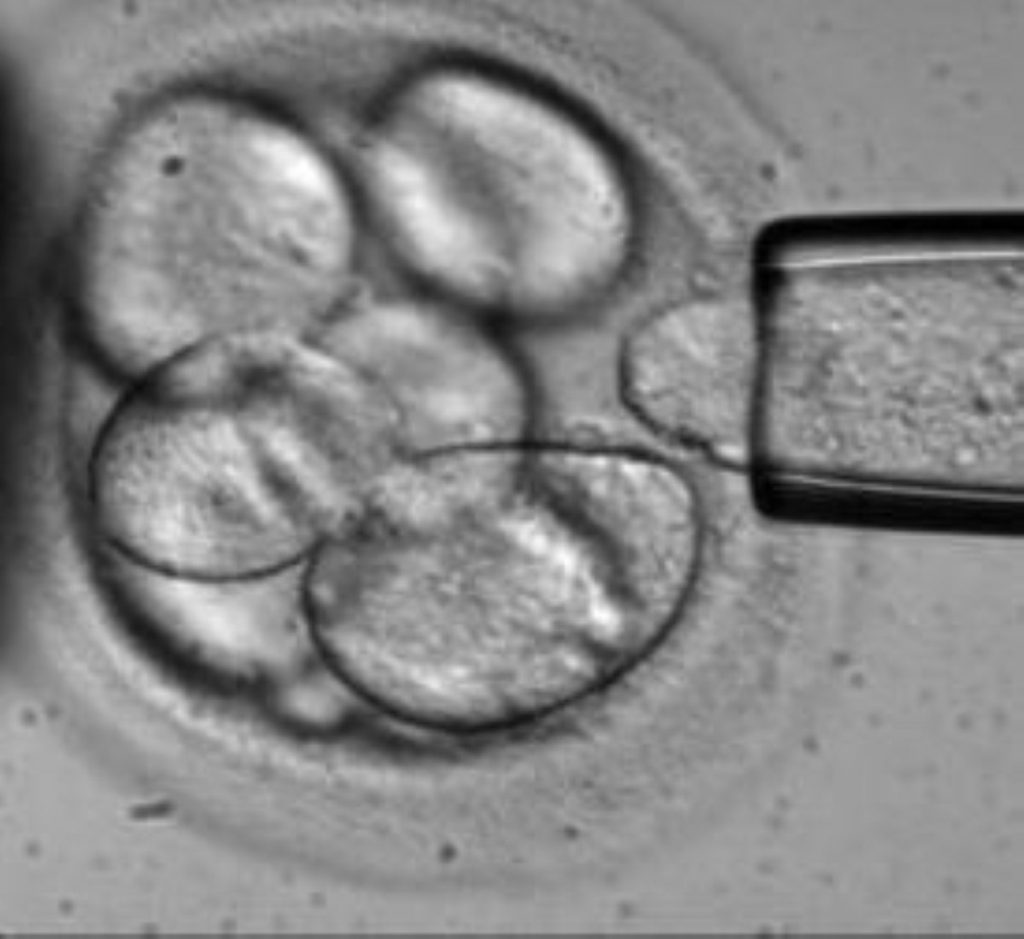

It is hoped cells taken from sick children could be used to create human or hybrid embryos for research, improving understanding of diseases.

Embryos created through somatic cell nuclear transfer, which uses skin cells taken from the sick child, could also be used to test therapies.

The Genetic Interest Group, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust and UCL Institute for Child Health argue research in this area is “critical” to the development of treatments.

The bill is currently going through the House of Lords this week and will enter the Commons later in the year.