Sketch: The art of being aggrieved

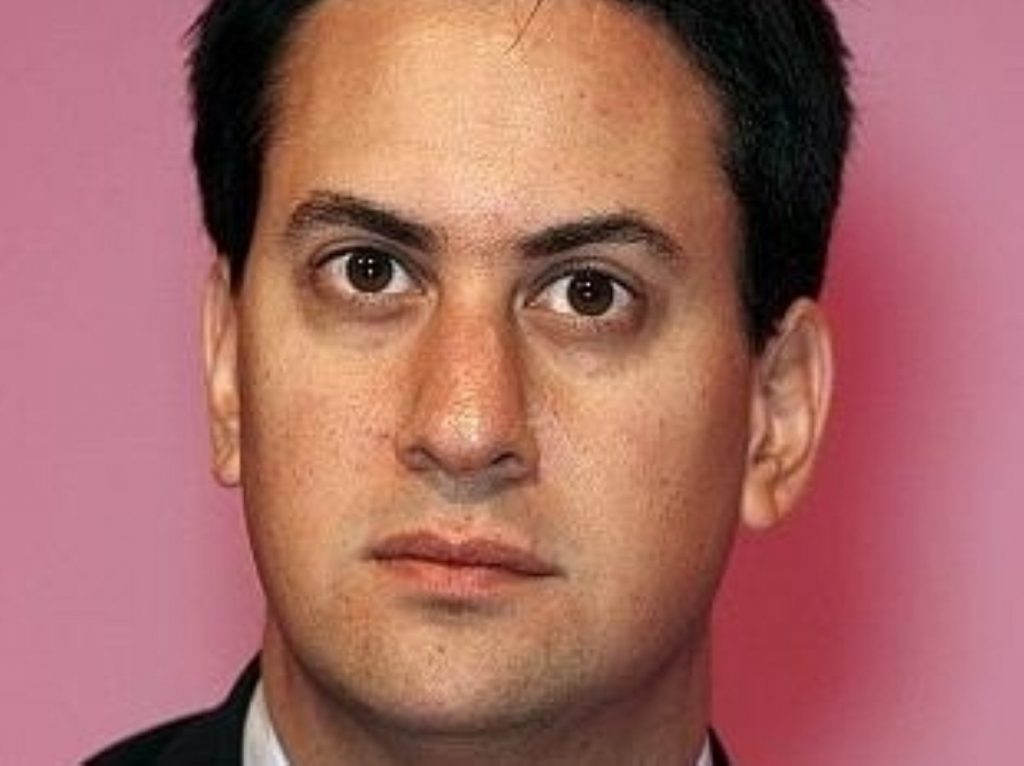

What the Police Federation chairman can’t do, Ed Miliband has down to a tee.

Whenever opponents of the government get a Cabinet minister, or even a prime minister, in the same room their solemn duty is to go for the jugular.

Ed Miliband gets the opportunity every week in prime minister’s questions. He’s well-practised by now, which may be why he pulled off an impressively competent demolition of the coalition’s policy on rape sentencing.

Paul McKeever, chairman of the Police Federation of England and Wales, only gets the opportunity for a bit of minister-bashing every so often. This may be why his performance at his organisation’s annual conference was so exquisitely, cringeingly awful.

Here, then, we have two political standoffs which show us the ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ of being an aggrieved challenger of government policy. To Bournemouth conference hall, then, for example number one – how not to do it.

Speaking without notes in front of a large audience is always challenging. Cameron pulled it off in that crucial speech to the 2008 Conservative party conference. McKeever, taking the plunge today, rambled his way through his speech. Theresa May stared from her seat on the stage in what looked like terminal boredom.

“We have a real concern about the way you operate – we believe you aren’t listening,” he said at one stage. She would raise her eyebrows, or look aside and sighed inwardly.

The problem was not his delivery – addressing the home secretary while gazing out at his audience, like a Jeremy Kyle-esque chatshow host – or his unremitting tone, that you’ve-hurt-my-feelings-and-now-you’ll-pay bleat. It was the hyperbole of his speech’s content.

He displayed a chart of the Treasury’s spending “solar system”, pointing to a small dot somewhere in the middle. “There we are,” McKeever explained, pointing out the police share of the government’s total budget. “We’re the size of Phobos or Deimos, one of Mars’ tiny little satellites.”

He displayed a graph which contrasted the international development department’s funding going up by 37% with the 20% cuts faced by police. Conservative party activists and workers, McKeever said, had been going to Africa in their summer holidays to “get a real understanding of what it means to be living in those communities”. Why hadn’t they spent time in Britain’s “vulnerable communities”? If they had, “how different our settlement might have been”.

He reminded May that last year he had recited an Alexander Pope poem at her. He said he had predicted a riot, before playing the song I Predict A Riot over footage of a – well, a riot. He showed her a picture of himself as a police officer in 1981, to demonstrate that he, the chairman of the Police Federation of England and Wales, had experience as a police officer.

It was all utterly overblown. It was all utterly ineffective. “It’s not my job to… tell you what you want to hear,” May said at the start of her poorly received speech. She appeared a little shaken up, true. The cough from that frog in her throat echoed through the silent hall. But although her voice may have wavered, her resolve did not.

What a contrast, then, with Miliband’s masterful management of PMQs in the commons this lunchtime. By the time the 12 ‘bongs’ sounded out and PMQs began, he had scrapped whatever his previous plans were about and was concentrating on justice secretary Ken Clarke.

Clarke is the Cabinet minister that just keeps on giving. His appearance on BBC Radio 5 Live this morning was as bumbling as usual, but it lacked the usual sparkle. Instead, his comments about rape provoked outrage from victims’ groups. He was ushered to Sky News to clear up his position, as Big Ben’s clock approached midday.

This was the masterclass – about as good a demonstration of how to be aggrieved effectively as you’ll find.

“The role of the justice secretary is to speak for the nation on matters of justice and crime,” Miliband began sombrely. So what was this about Clarke distinguishing between “serious rape” and “other categories of rape”?

Cameron had an easy escape from this, explaining that he hadn’t actually heard the interview. Busy man, the prime minister. Lots of things to do. Hasn’t got time to listen to Victoria Derbyshire on 5 Live, at least.

“Let me tell him what the justice secretary said,” Miliband said calmly, having anticipated this answer. Clarke had attempted to distinguish between “forcible rape” and “serious rape”. No one does quietly seething outrage like a Labour frontbencher, and Miliband is the best of the lot. He gives the impression he has been offended, nay wounded, to the very core of his being. “The justice secretary cannot speak for the women of this country when he makes comments like that,” he said. And then, his voice hardening: “The justice secretary should not be in his post at the end of the day.”

The prime minister repeatedly retreated to the “terrible fact” that just six per cent of reported rapes end up in a successful conviction. There are usually strong fundamentals for Cameron to retreat to, on all the big issues of the day. Rape only crops up every so often, forcing the PM to retreat to generic tough lines on law and order. “What matters is, do we get more cases to court, do we get more cases convicted, do we get more decent sentences?” With more plea bargaining, the coalition’s proposed policy, the fear is that won’t be the case.

Where McKeever was disjointed, Miliband’s attack had structure. He broadened out his criticism to include “the way he [Cameron] runs his government” as the questions progressed. “People are rightly very angry,” he fumed. But the prime minister was on good form too, underlining his desire to “prosecute”, to “sentence”, to “convict!” all rapists. Only when he accused Miliband of jumping the bandwagon did he go too far, galvanising Labour MPs into very loud protests.

The usual chirpy contributions from backbenchers, a part of every PMQs, seemed somewhat appropriate. Miliband and Cameron were, for once, having a genuine debate about an extremely serious issue. A shame, then, that backbenchers were on default mode.

They should have been scattered around the audience in the Police Federation conference hall. Now that would have livened things up, for McKeever needed all the help he could get.